When you look at an artwork, are you truly observing what’s there, or are your assumptions shaping what you see? This is a concept that intrigues artist Maisie Maud Broadhead.

An Associate Lecturer at the Royal College of Art, Broadhead is known for her photographic portraits that reimagine 17th century Dutch paintings of domestic interiors. Her work creates a sense of illusion and the uncanny, mixing historical references with contemporary processes to play with our expectations of how photographs and paintings should look.

Two of her works, Artist Sitting and Explorer, have been acquired by Royal Museums Greenwich and are on display in the Queen’s House.

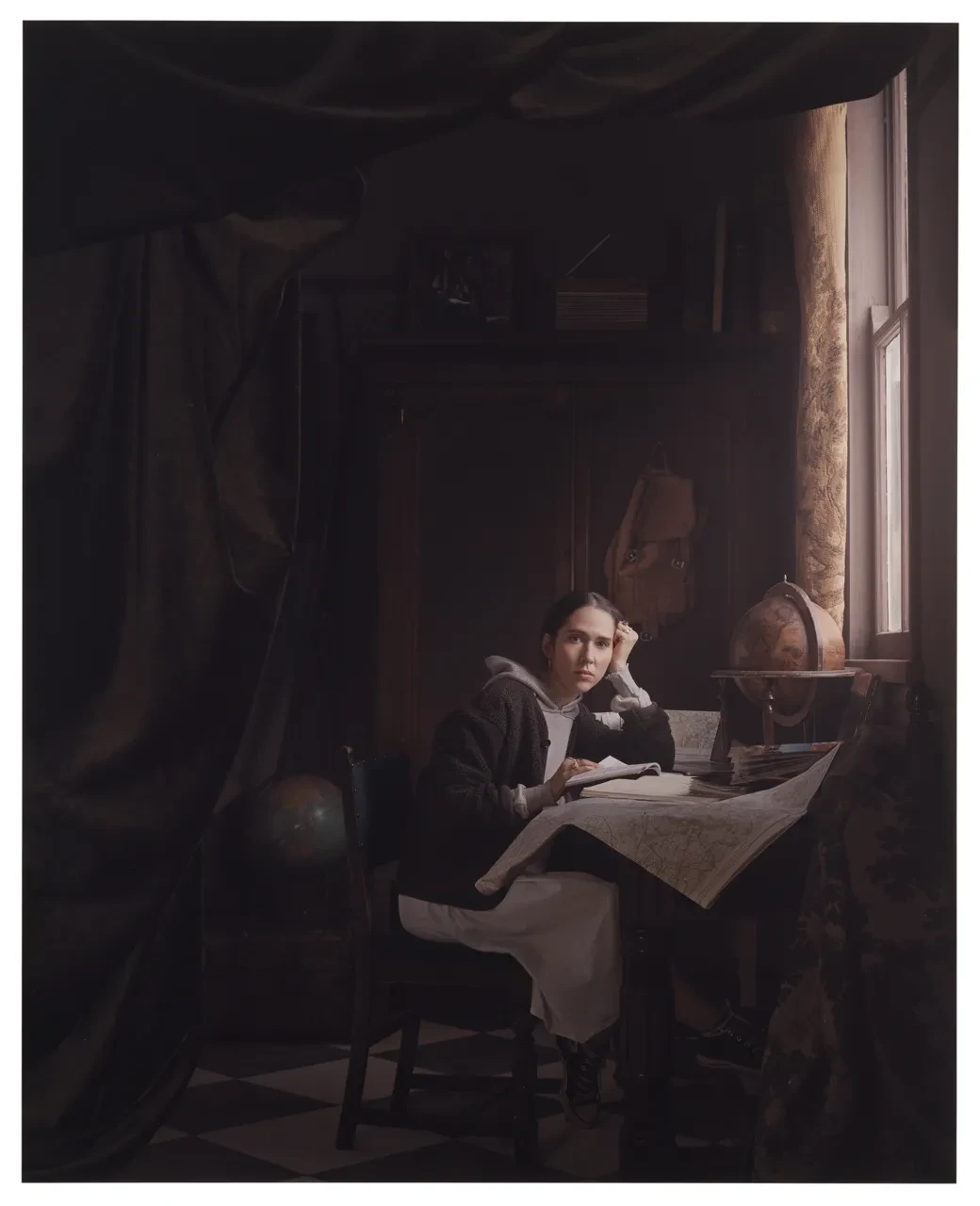

In Artist Sitting (2020), a woman turns away from a desk filled with art materials to glance at the viewer. Explorer (2020) shows the sitter resting her head on her hand, surrounded by maps and navigational instruments. The works join Rear Window (Dinner), acquired by the Museum in 2023, which depicts the aftermath of a disordered dinner scene.

Here, Broadhead meets with Victoria Lane, Senior Curator of Art and Identity, to discuss her influences, blurring boundaries between art forms and sustaining creativity.

Explore the works

Explore the works

Reinserting women into history – and depicting women as active historical participants – is a characteristic of your work. Can you tell us about the concepts behind the photographic portraits on display in the Queen’s House?

For this series of photographic portraits, I was inspired by the paintings of Johannes Vermeer. There’s something quite beautiful in the way he highlights people who wouldn’t ordinarily be depicted.

Both Artist Sitting and Explorer feature my sister Bella as the subject. I grew up in a large female household – I’m one of four sisters – and it felt important to put a sister of mine in there. They are the heartbeat of my life and family.

For Artist Sitting, I was interested in how Vermeer observed women in quite calm, domestic spaces, often doing chores or frozen in time. His use of light is rather wonderful – particularly how it draws you to a face or a very still moment. Although Bella was my subject, the work was about that quiet moment you get when you’re trying to work through a project. Like many of my works, it was about a reflection on a moment in time.

Explorer takes inspiration from Vermeer’s The Astronomer. While this photographic portrait depicts Bella as more of an internal explorer, in real life she’s an intrepid adventurer. She’s spent time living on a mountain in Colorado and she’s done the Camino de Santiago trail. She’s more of an explorer than I will ever be! It’s important for me that my work incorporates elements of the sitter’s character too.

Your artworks are almost illusions. They highlight the slippage between the painterly and the real, and play with the way the viewer perceives art. How do you go about making your pieces?

Often people say to me, “I love your paintings,” but they’re actually photographs! I like it when you look at something, and realise that you’ve allowed your historical knowledge of what art should look like – rather than your eye – to interpret what’s in front of you, and then you have to autocorrect. I like that play of: “What is it that you’re looking at?”

My images are more like making, rather than a photograph. For this series of photographic portraits, I created and built the set, linked to imagery based around Vermeer.

When making my works, I often take hundreds of pictures, changing the focus to highlight different elements. I use continuous lighting – like in films – and smoke machines and lots of diffusion paper, which gives a milky, smoky effect so you get that sense of softness. I spend a long time making the set in the real space, to create the composition rather than working in the digital.

I then composite all the images together by hand in Photoshop, to create one image – a bit like a collage. What gives the final images a slight painterly quality is that a lot more things are in focus than there should be, if it was strictly a single shot.

As artists paint, their eyes move around the entire painting, so they're sort of painting everything to a degree in focus. I sometimes like to see if I can do everything in camera with little to no Photoshop. It depends on the project.

I like to create work that presents a sense of the uncanny. I want viewers to think: “Am I looking at something from the past, or something from the present-day?” In Artist Sitting and Explorer, all the clothes that are featured are mine – none of them are historical. I observed the original forms and silhouettes of the garments in Vermeer’s works, and used modern-day equivalents that followed the same shape and worked tonally.

Do you have any advice for emerging artists?

One of the most important things I’ve learned is that the community around you is crucial to sustaining your creativity. Make sure you’re around people you can have honest conversations with about work, motivation and future projects.

Conversation is really important: don’t let people go. I’ve found that as I get older, people are more willing to help you. In my experience, the more generous you are with other people, it comes back to you too.

As an artist, you have to continually put the work in. The moment you get to a comfortable stage, where you think “this is who I am,” then the work tends to go a bit flat. It’s up to you to slightly reinvent yourself all the time, and that’s quite hard to do.

What does it mean for you to have Artist Sitting and Explorer shown in the context of the Queen’s House – a space commissioned by women, for women?

The Queen’s House is such a beautiful space. When I went to see my work Rear Window (Dinner) in situ, I fell in love with the black and white chequered floor in the Great Hall. It still blows my mind that my work exists in spaces like this.

Historically, the type of people who were painted and represented in museums and galleries were often famous or wealthy. When we go to these places, we see artworks hanging on the wall, and we give them importance because of the way they’re framed or positioned.

I love the idea of playing with the historical framework, of inserting a little bit of my world into these spaces. I like the fact that some of my more ‘humble’ subjects have ended up being displayed in quite prestigious places just for being themselves.