What can the back of a painting tell us? Paintings conservator Lucy Odlin sheds some light on the often overlooked underside of Tudor masterpieces.

Visit the National Maritime Museum

In the 16th century, artists in Britain and Northern Europe very often chose to paint on wooden panels as the hard, even surface of the wood allowed them to apply the paint smoothly, in a detailed and delicate way. This was especially suited to painting the richly embroidered costumes and elaborate jewels worn by the kings, queens and people of high society who typically had their portraits painted.

The back of a painting is not the first place most people today would (or could!) necessarily look, but by closely examining the reverse of a panel we can learn a great deal about how it was made into a painting support.

Where did the wood come from?

Artists generally chose to paint on oak. However rather than using English oak, wood was imported from the Eastern Baltic region (modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) as its colder, more stable climate enabled the trees to grow slowly and evenly. The tree rings, which represent the seasons, would have been close together and evenly spaced, producing high quality oak that was far easier to cut down into relatively thin, rectangular boards for painting. By comparison, English oak would have had an irregular, twisted grain due to greater changes in weather throughout the year, meaning it was far more difficult to cut down into a flat panel for painting with the hand tools available in the 16th century.

Ways of studying an oak panel

Dendrochronology, x-rays and raking light

Oak panels used for painting can be analysed using a sophisticated method of analysis called ‘dendrochronology’, or tree-ring dating. This can help to give an approximate date to a painting as well as identify the region where the tree would have originally grown. All of the panel paintings studied during the Tudor Paintings Project were analysed by dendrochronologist Ian Tyers, an expert in his field.

Ian’s work revealed that the majority were painted on Eastern Baltic oak, although there was also one example of English oak being used. This was found on a less accomplished portrait, somewhat provincial in style, thought to be Richard Barrey, Keeper of Dover Castle during the Armada campaign. It is possible that English oak was chosen because the painter in question may have been working some distance away from a major import destination such as London, making high quality imported oak more difficult to find.

X-rays can make the narrow, straight grain of Eastern Baltic oak visible if the panel has a lead-containing ground layer. This can be seen in a portrait thought to be of Richard Hawkins (figure 2) from the Museum’s collection.

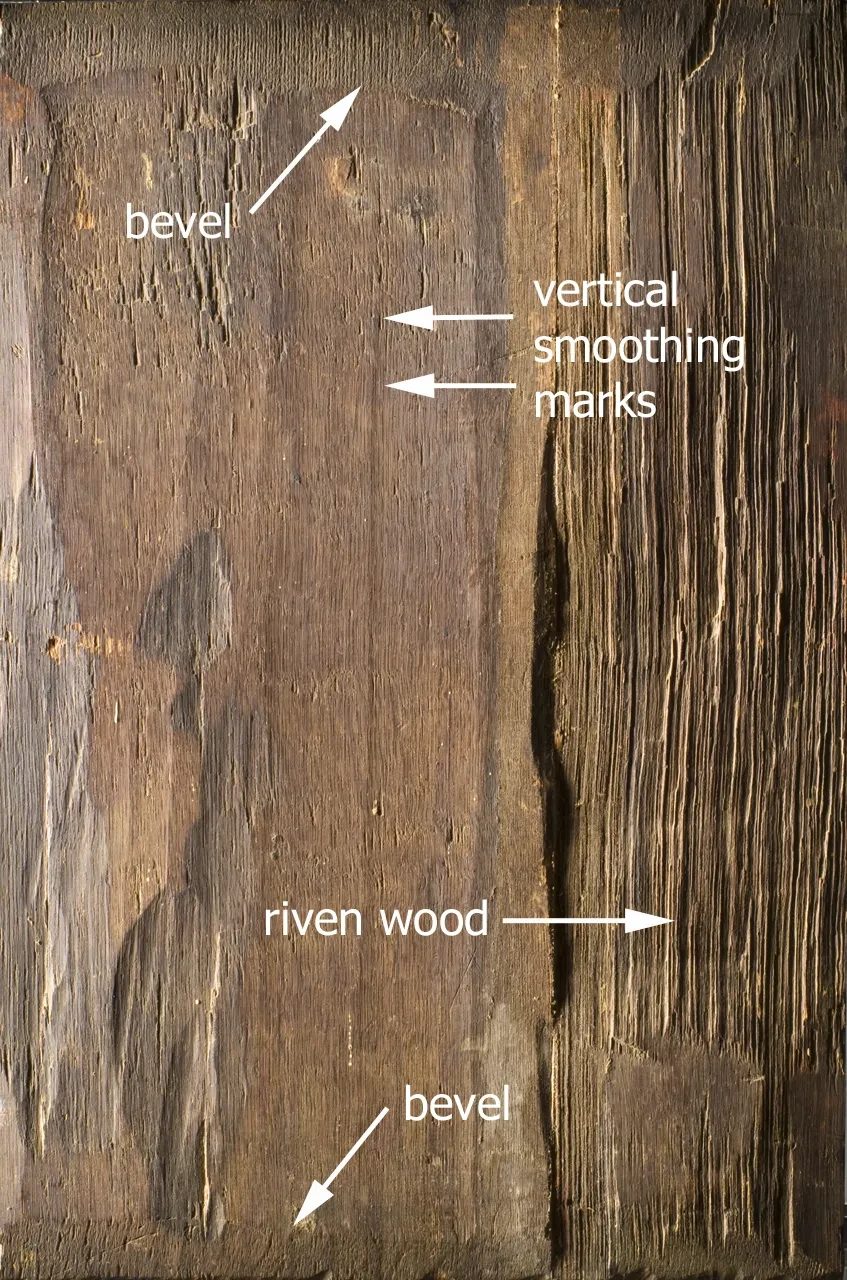

Raking light – a bright light positioned at a sharp sideways angle to the painting – is a useful, low-tech way of studying the wooden surface of a panel as it exaggerates any tool marks or other features, making them easier to identify.

Raking light showed that the back of the Richard Hawkins portrait (figure 3) had been constructed from two boards, with the join running from top to bottom just off-centre to the right. The board on the right of the panel has a strong vertical texture. This is because the wood here has a ‘riven’ surface, created when the board was split from a larger piece of wood. We can see that since then, no other tools have been used to make this board smoother or thinner; for this reason a riven surface is known as ‘undressed’ wood. By contrast, the board on the left has long, vertical smoothing tool marks, created when a handheld plane was used to refine the rough appearance of the wood.

The painting of Richard Hawkins has a slightly longer, thinner format which does not correspond to the typical 4:3 aspect ratio favoured by artists during the 16th century. While this could of course be an intentional decision by the artist, in this case, it was possible to see from the reverse that the bevel, or thinned outer edge still visible at the top and bottom (see figure 3), had been completely removed on the left and right sides. Based on the width of the surviving top and bottom bevels, it seems that around 3.5 cm had been removed from either side. Prior to these subtractions the painting would once have fit the typical 4:3 aspect ratio.

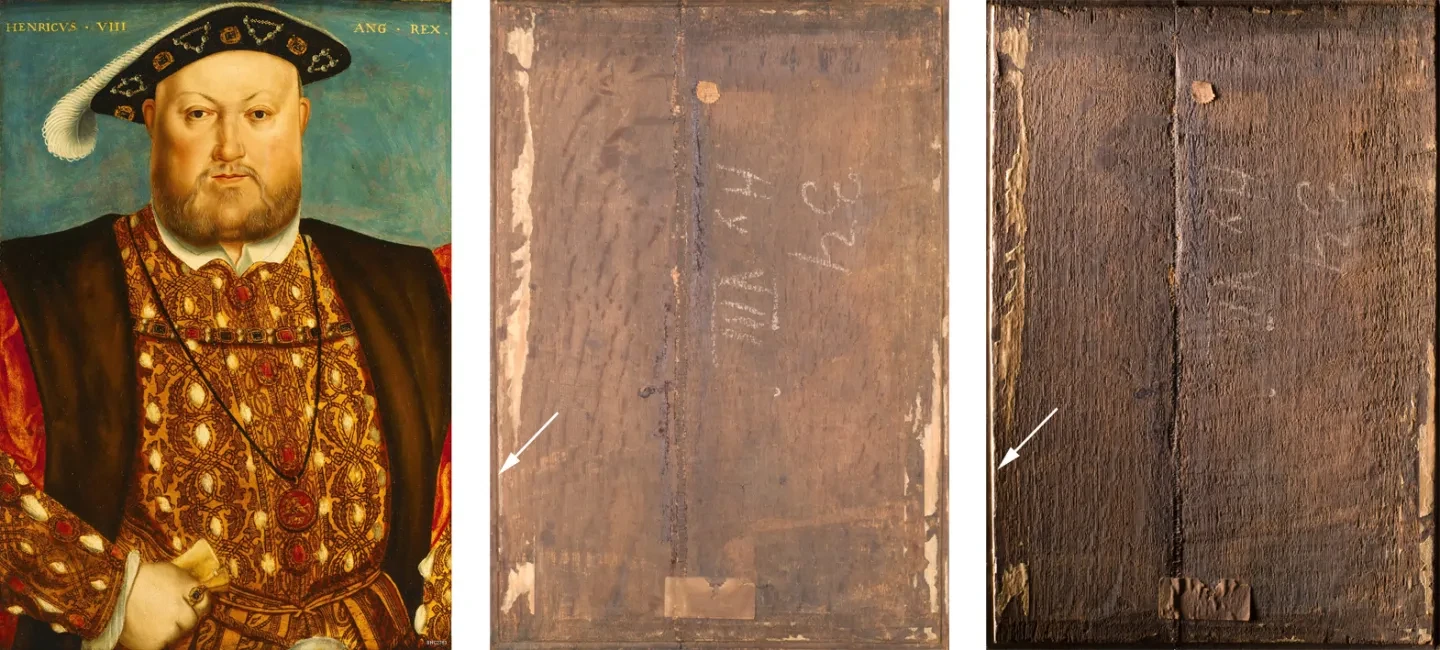

The back of a panel can also give clues as to how it may have originally been displayed. A rebate, or stepped outer edge that is thinner than the main panel, can be a sign that the painting was displayed within a fixed or ‘engaged’ frame or decorative interior panelling scheme. This painting of Henry VIII from the Museum’s collection (Figure 4) is one such example. There is an original rebate on all four edges (which also tells us that it has not been cut down), just visible at the far left in the normal and raking light images.

Of course, studying the reverse of a panel should be done together with close examination of the paint layers on the front, the materials used and the technique with which they have been applied. This way we can piece together the evidence and a more complete picture of historic craftsmanship and artistry has emerged of our Tudor paintings.

Lucy Odlin is a paintings conservator undertaking a 6-month HLF-funded Research Internship in the Conservation Department of the National Maritime Museum. She is working on the Tudor Paintings Project, involving close examination of the materials and technique of 20 portraits on canvas and panel, dating from around 1550 to 1600, many of which are on display in the Queen’s House. The majority of the paintings are on wooden supports, typical of artistic practice at the time, and this blog aims to gives an insight into what the often-overlooked back of a painting can tell us.