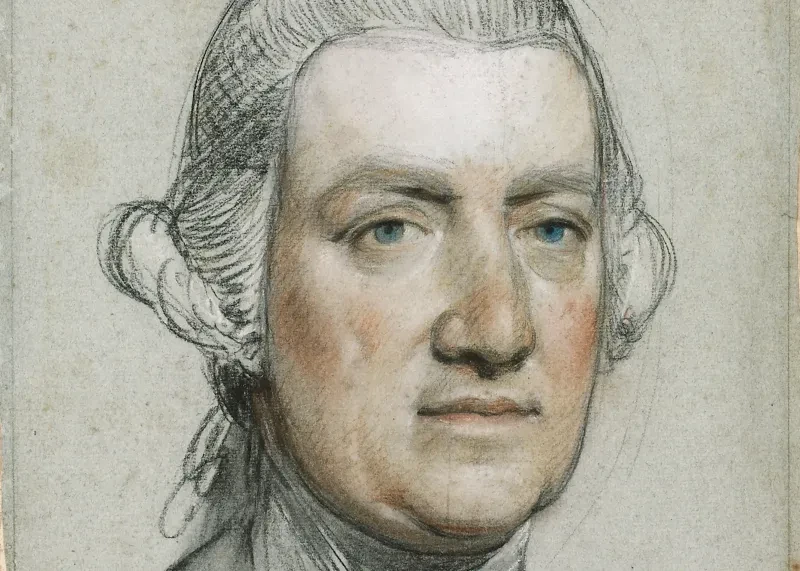

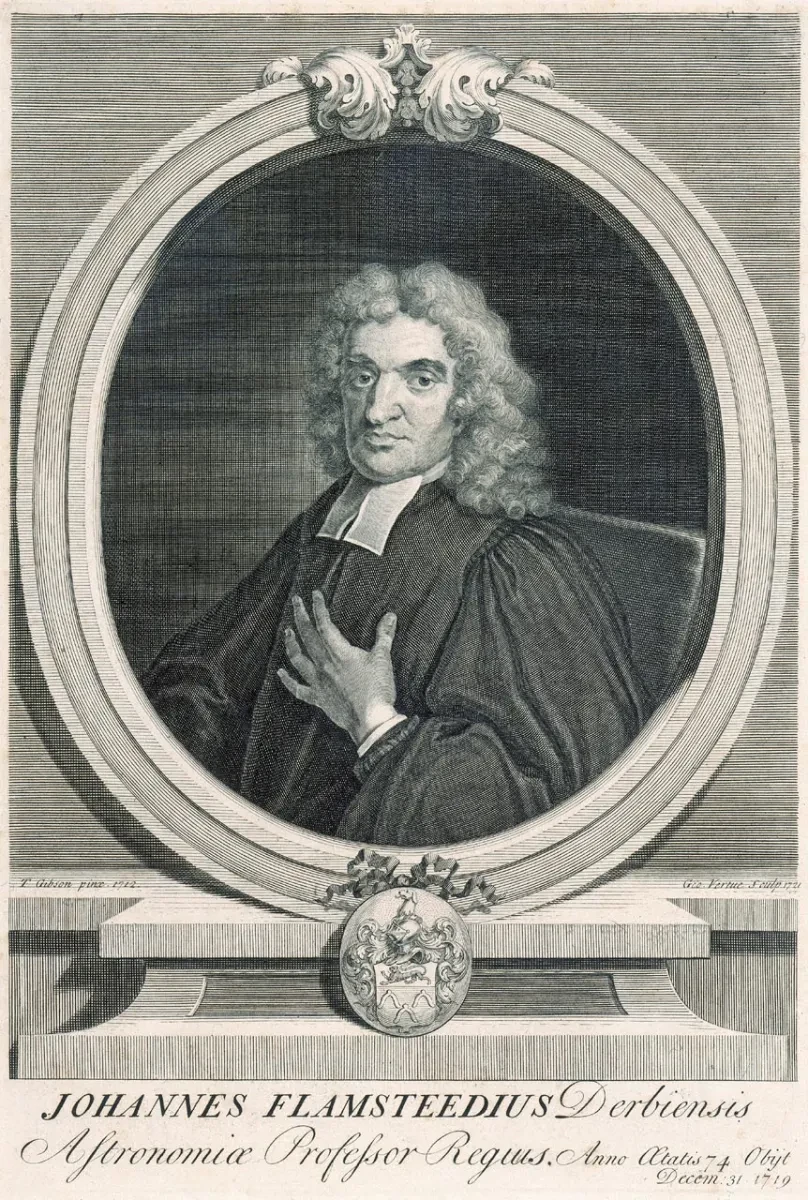

John Flamsteed (1646–1719) was an eminent English astronomer.

He was appointed as the first Astronomer Royal by King Charles II in 1675, a position he held for 44 years.

Flamsteed's task as ‘astronomical observator’ or Astronomer Royal was to create an accurate map of the night sky which could be used to help determine longitude and improve navigation at sea. The Royal Observatory in Greenwich was founded in the same year to aid him in this task.

Flamsteed played an integral role in establishing the Observatory’s reputation as a pioneering centre of astronomy and timekeeping.

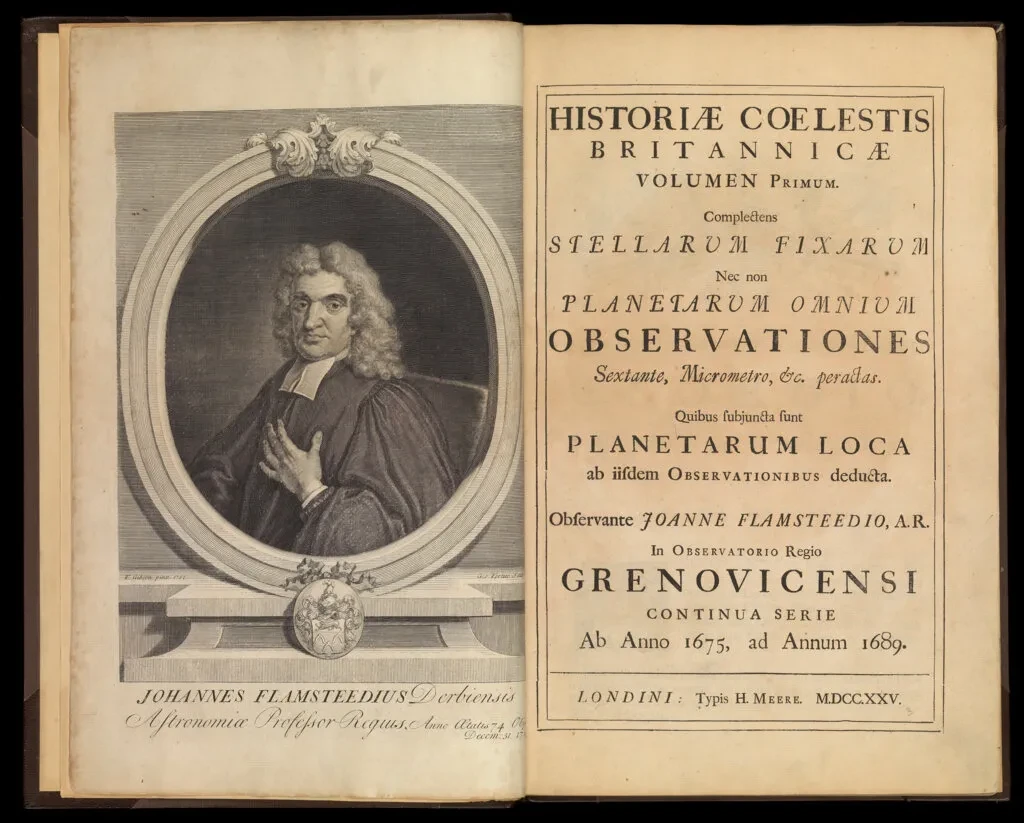

His key works were a catalogue of 3,000 stars known as Historia Coelestis Britannica, and the largest and most accurate star atlas that had ever been published: Atlas Coelestis.

However, his later years were mired in controversy over his hesitancy to share his work before perfecting it, leading to Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley publishing a mistake-riddled version against his will in 1712.

Discover more about the life and work of John Flamsteed.

Early life

John Flamsteed was born and educated in Derbyshire, England.

He became interested in astronomy and studied it independently with the help of local scholars. Despite postponing his studies due to ill health, he was later awarded a degree from Jesus College, Cambridge.

His early work in astronomy focused on the observation of solar eclipses, determining ‘solar parallax’ from observations of Mars, and devising a formula for converting solar time to mean time in the early 1670s.

Flamsteed was also ordained a clergyman in 1675.

The longitude problem

In 1675 astronomers were exploring methods of determining longitude at sea. Although latitude (distance north or south) was relatively easy to determine by the Sun and stars, longitude (distance east or west) was proving hard to work out.

As European vessels made longer voyages worldwide, a solution to the ‘longitude problem’ became increasingly important. It would make navigation easier, safer and more efficient, in turn boosting Britain’s maritime trade and its standing as a sea power.

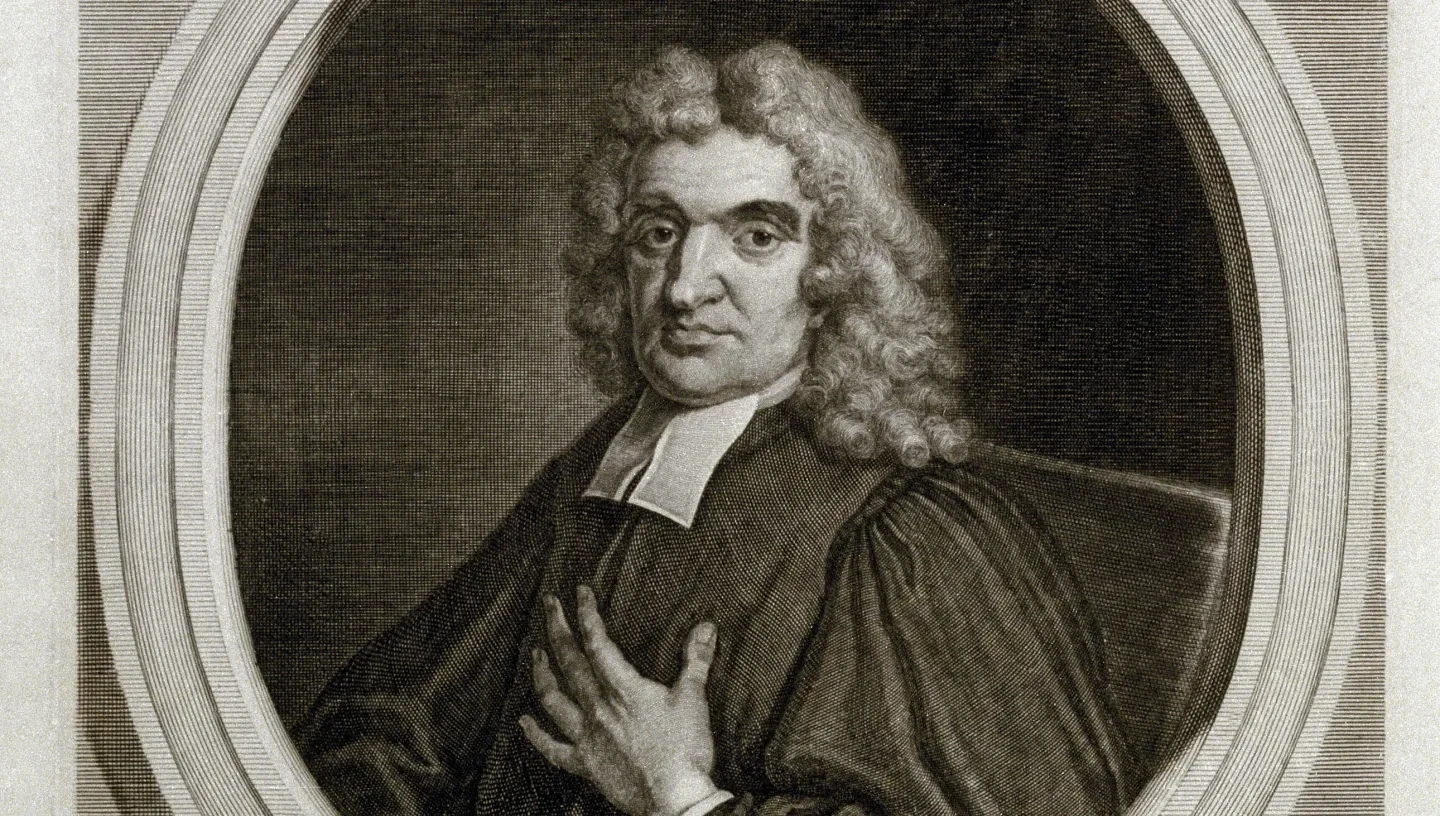

In 1674, French astronomer Sieur de St Pierre claimed to have improved the ‘lunar distance method’, a way of determining longitude using the position of the Moon against the stars.

Flamsteed, alongside many eminent scholars including Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke, was part of a committee asked to supply astronomical observations to test this theory.

The committee concluded that although St Pierre's proposal was not viable, the King should consider establishing an observatory where astronomers could work on improving the lunar distance method themselves.

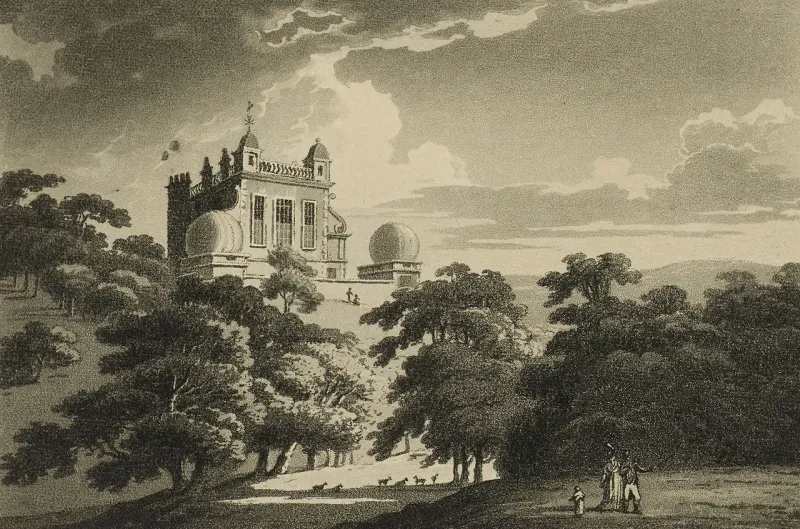

Founding of the Royal Observatory

Flamsteed was appointed 'our astronomical observer' by King Charles II on 4 March 1675, and the Observatory was founded on 22 June of the same year. Flamsteed laid the foundation stone of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich on 10 August 1675.

Charles II instructed him to work on “the rectifying of the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so much desired longitude of places for the perfecting of the art of navigation."

Flamsteed lived and worked in the Tower of London while the Observatory was being constructed. According to legend, his astronomical observations were often disrupted by the ravens at the Tower, who would perch on and foul his telescopes. The King almost ordered the ravens to be removed – until he was told of the superstition that said if the ravens left the Tower the Crown would fall.

Flamsteed later moved all his equipment to the Queen's House in Greenwich, positioned just down the hill from the Observatory building site, allowing him to oversee the work.

A home for the Astronomer Royal

John Flamsteed moved into the Royal Observatory during the summer of 1676.

The main Observatory building soon became known as Flamsteed House, named after its first occupant. It was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and originally consisted of a ground-floor living space topped by the ‘Star Room’, later called the Octagon Room. The room's tall windows and walls were designed to give Flamsteed a panoramic view of the night sky and house astronomical instruments and long pendulum clocks.

Unfortunately, none of the walls aligned with a meridian. Astronomers use meridian lines – imaginary lines running due north or south of the viewer – as a reference when making star observations. As a result, most of Flamsteed's and his successors' observational work was done in outbuildings, with Flamsteed House serving mainly for living and receiving visitors.

Margaret Flamsteed

John Flamsteed married Margaret Cooke in 1692. Throughout their marriage Margaret was closely involved with both life and work at the Royal Observatory.

Margaret was well educated: Flamsteed's records show that she occasionally assisted during observational and calculating work, and manuscripts in the Royal Greenwich Observatory archive in Cambridge show that she studied mathematics and astronomy.

These studies may have reflected those of Flamsteed's paid assistants and paying pupils, who Margaret would have taken care of as part of the general management of the household.

Margaret also oversaw the publishing of her husband's life’s works after his death.

What did John Flamsteed do at the Royal Observatory?

Flamsteed made observations of the Moon to compare with Newton's gravitational theory, made tables of the Sun's motion, measured the latitude of Greenwich, and calculated the inclination of the ecliptic and the position of the equinoxes. He also created tables of atmospheric refraction and tidal patterns.

However, his key works were the Historia Coelestis Britannica, a catalogue of over 3,000 fixed stars listed by their Right Ascension (celestial longitude) and Declination (celestial latitude), along with the Atlas Coelestis, or star atlas, both published posthumously.

John Flamsteed and Isaac Newton: a bitter rivalry

Flamsteed began work on a new star catalogue after moving into the Observatory in 1676. Nearly 30 years later it was still incomplete.

During his time as Astronomer Royal Flamsteed had invested a considerable amount of his own money into his work at Greenwich, paying for equipment and assistance to compile the data.

Flamsteed had also devoted a large portion of his life to the catalogue, and so refused to publish it until he was sure the data was all correct, fearing serious reputational damage.

However, some felt he was unreasonably withholding the catalogue from the wider science community. Leading astronomers of the time including Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley found that their own work required Flamsteed’s observations.

Friction built between Flamsteed and other astronomers, who were becoming increasingly frustrated by the impact he was having on their work – especially Newton.

Newton was president of the Royal Society. Alongside other astronomers he persuaded Queen Anne to appoint a Royal Society committee with power at the Royal Observatory. This included the authority to instruct the Astronomer Royal on what to observe and when to publish. Known as the ‘Board of Visitors’, this influential group would shape the Observatory’s work for the next two centuries.

Flamsteed finally provided sealed copies of his observations to the Royal Society, but was blindsided when 400 copies of these unfinished drafts were published with edits and an introduction by Edmond Halley in 1712.

Flamsteed was furious. In a letter written in 1715, he stated how he had been “unworthily, nay, treacherously” dealt with by Newton:

“I wonder that he should so impudently pretend to dispose of the printed copies of my works, i.e. the printed observations: they cost him not a single hour’s labour or watching, nor was he at one penny expense in the making them; but besides my daily labour and watchings, when he was asleep in his warm bed, it had cost me above £2000 out of my own pocket … in instruments and necessary assistance.”

Flamsteed managed to obtain 300 copies of the work in 1716 and publicly burned them on a bonfire in Greenwich Park.

John Flamsteed's death

John Flamsteed died on 31 December 1719. He was succeeded as Astronomer Royal by Edmond Halley in 1720.

Flamsteed had worked on his catalogue until his death. Margaret collaborated with the Observatory's former assistants to publish the full version of Historia Coelestis Britannica in 1725. It was considered a fundamental work in British astronomy, and was used by future astronomers for decades.

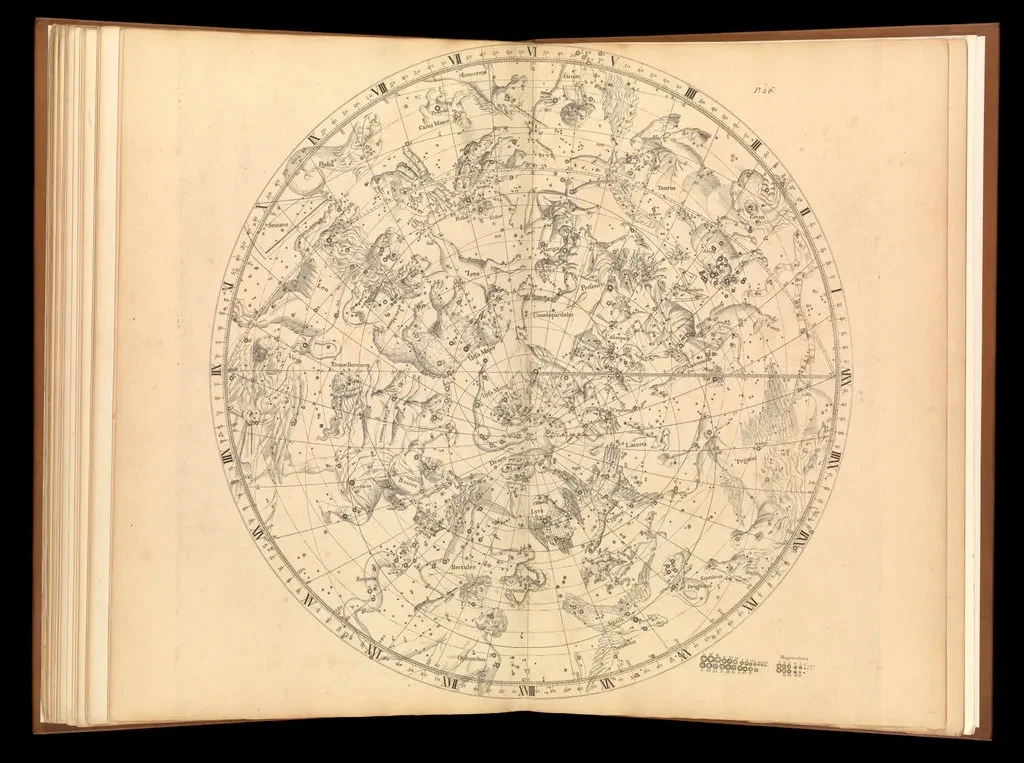

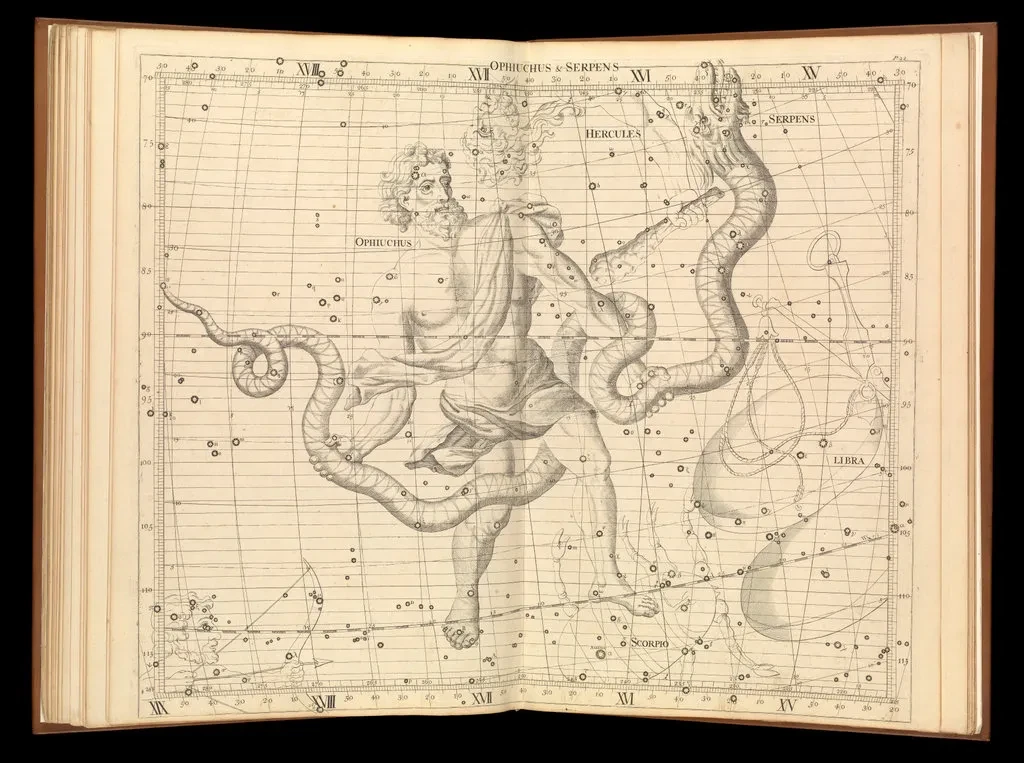

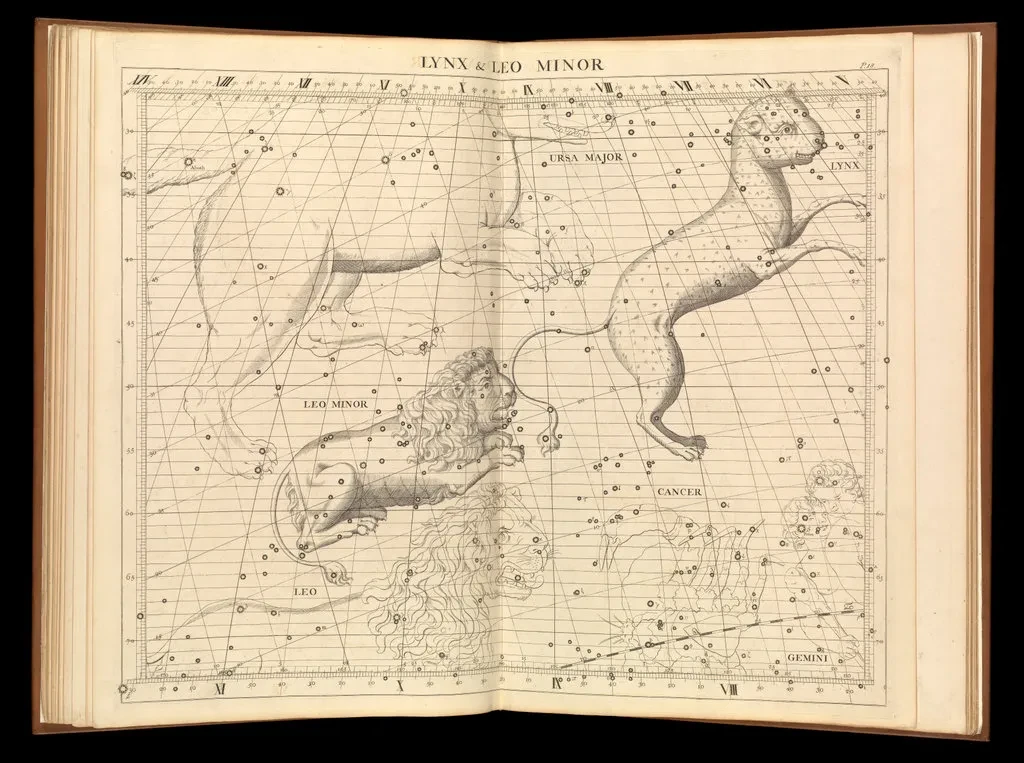

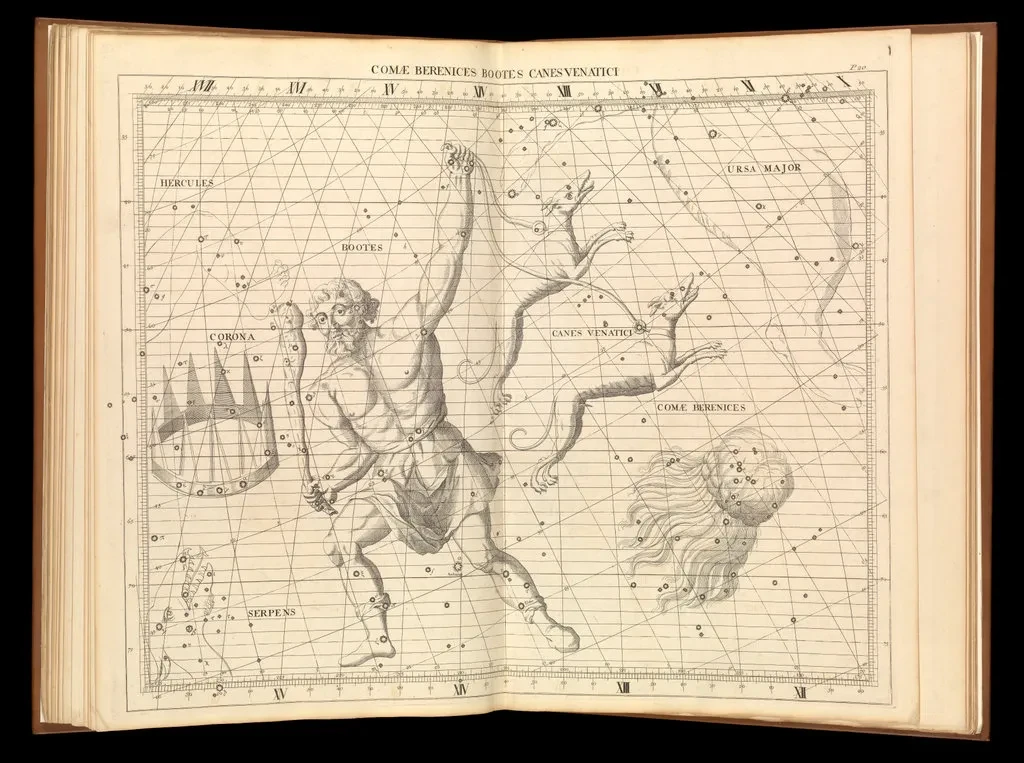

Margaret also oversaw the publication of the Atlas Coelestis in 1729, which at the time was the largest and most accurate star atlas ever published. It featured 25 maps of the constellations based on designs by James Thornhill, who designed and painted the Painted Hall in Greenwich.

Without Margaret, these works may never have been published.

Explore the Atlas Coelestis

John Flamsteed's legacy

- Flamsteed House still bears his name today.

- John Flamsteed features on the ceiling of the Painted Hall in Greenwich amongst many other notable and highly respected figures of the time.

- Flamsteed crater on the Moon and the Flamsteed Astronomy Society based at the Royal Observatory are named in his honour.

- Some stars are still known today by the numbers Flamsteed gave them.