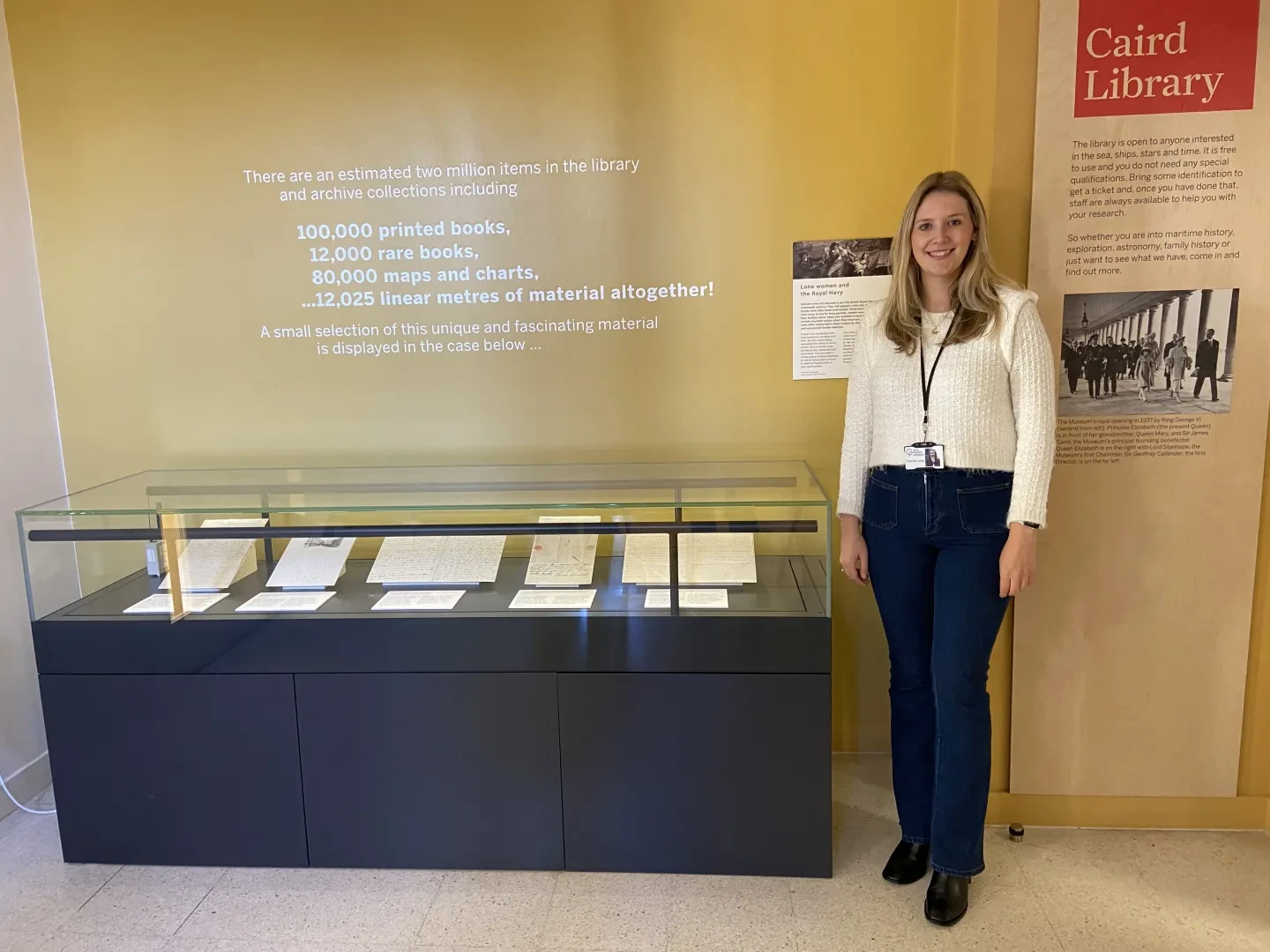

The Caird Library & Archive’s new display case highlights first-hand accounts of women’s experiences and contributions to the nineteenth-century Royal Navy

Beyond farewell

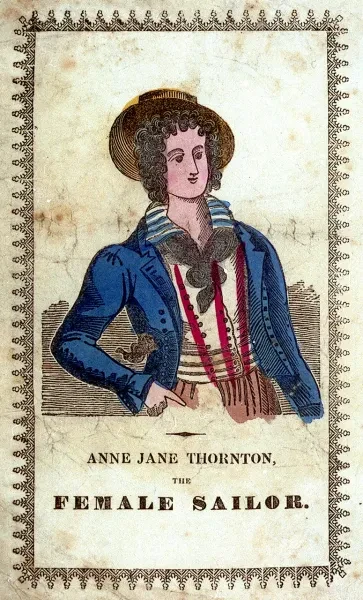

‘The Sailor’s Farewell’ is a popular emotional image of familial separation. It portrays wives being left behind on shore, their arms longingly outstretched towards their husbands as they get ready to sail away. The women’s faces are forlorn, and their young children cling to them, anchoring them on shore, emotionally capturing the pain of separation experienced by many naval families; however, this image does not reveal what happened to the women after their husbands sailed away.

Although women were not able to join the Navy as sailors, they still played essential roles.

Whilst their male relatives were away at sea for long periods, women would raise their families alone and often brought up their sons as future recruits. Many also worked in naval dockyards or nursed wounded sailors. Naval officers were often supported in their careers by their influential or well-connected female relatives who used their patronage and personal networks to support their husbands’ and sons’ ambitions for jobs and promotions. Women with husbands in the Navy sometimes travelled with them, facing challenging voyages, creating homes overseas away from the support of their friends and family in Britain.

The stories and experiences of women have often been overlooked or acknowledged only at a point of separation and reunion, which denies them their agency and hides the value of their contribution to the Royal Navy. However, research using the manuscripts collection at the Caird Library and Archive reveals a rich collection of material written by women throughout their lives, exploring how women survived on their own for long periods, handled the challenges of long-distance marriages and parenting, and experienced widowhood.

Good communication was essential for naval families. Letters helped individuals to manage distance by keeping each other informed of changes at home as well as at sea. They were an intimate space to discuss feelings but could also function as practical tools in petitioning for financial help and opportunities.

In her own words

The display consists of five original letters written by women in their own words. These letters were selected, among many hundreds of others, as examples to provide insights into the experiences of women left on shore during key life moments and challenges. The display has a life-cycle structure and covers themes from long-distance marriage, pregnancy, parenthood and familial separation to illness and the death of a partner.

Intimate letters

The items on display document how women often faced important experiences, such as pregnancy, alone. Childbirth was a particularly dangerous experience for women at the time and Sally Woolnough’s letter to her husband stationed in Martinique reveals intimate details of her anxieties regarding this, as well as how she independently managed their household.

Marital correspondence reveals that naval wives often had more agency than was common in civilian households, regarding the running of homes and financial management, as naval husbands often trusted their wives to manage their finances and make decisions on where to live.

Parenting and cultural exchange

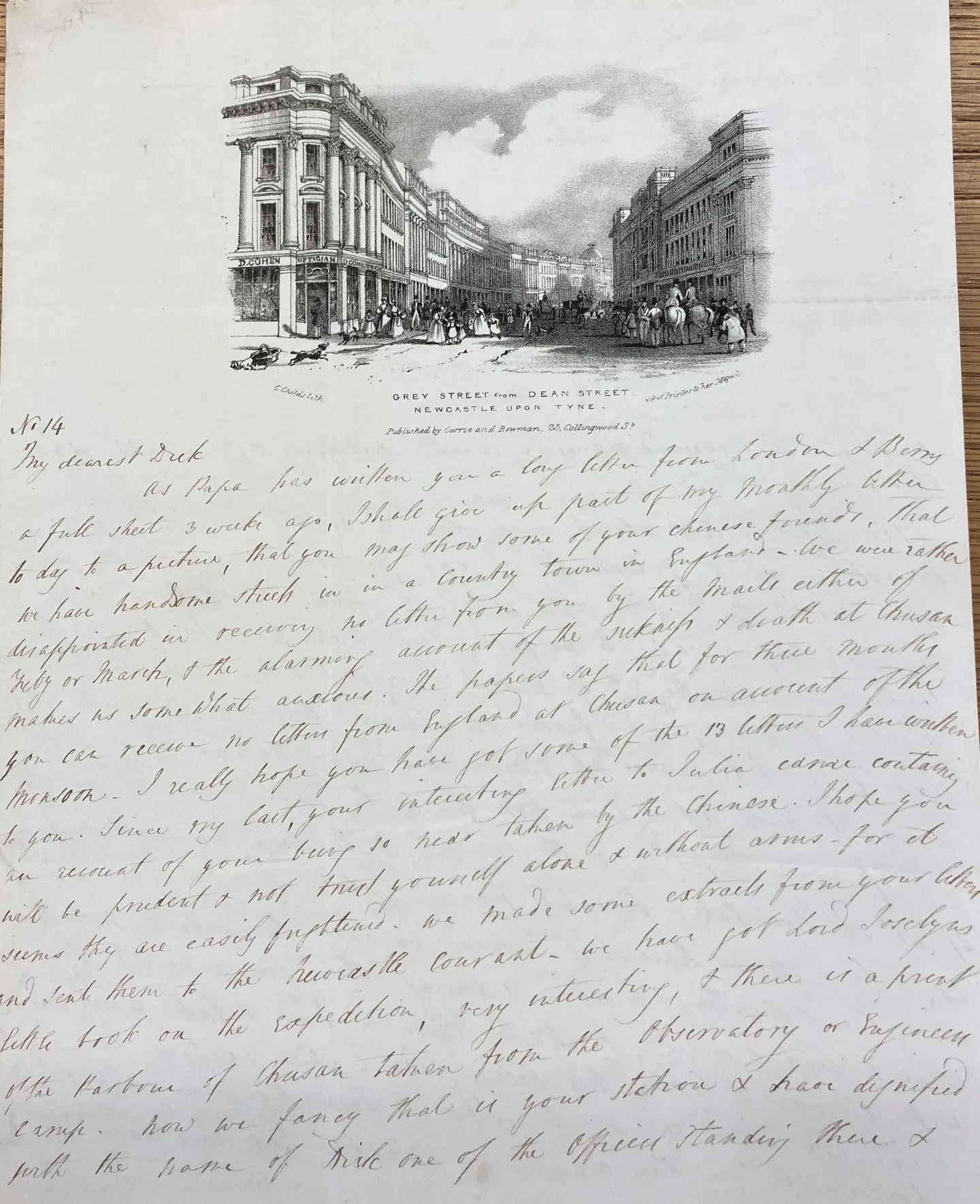

Letters could also be written for a public purpose. Emily Collinson chose to include a print of Newcastle in her letter to her son stationed in ‘Chusan’ China so he could show his ‘Chinese friends’. In return, she shared extracts of his letters in newspapers at home.

Although women were unable to provide practical advice on life at sea, mothers were nonetheless important to their sons’ careers as they were able to promote their activities and write on their behalf to aid their entrance into the naval academy, first posts and promotions.

Ill health and the challenges of correspondence

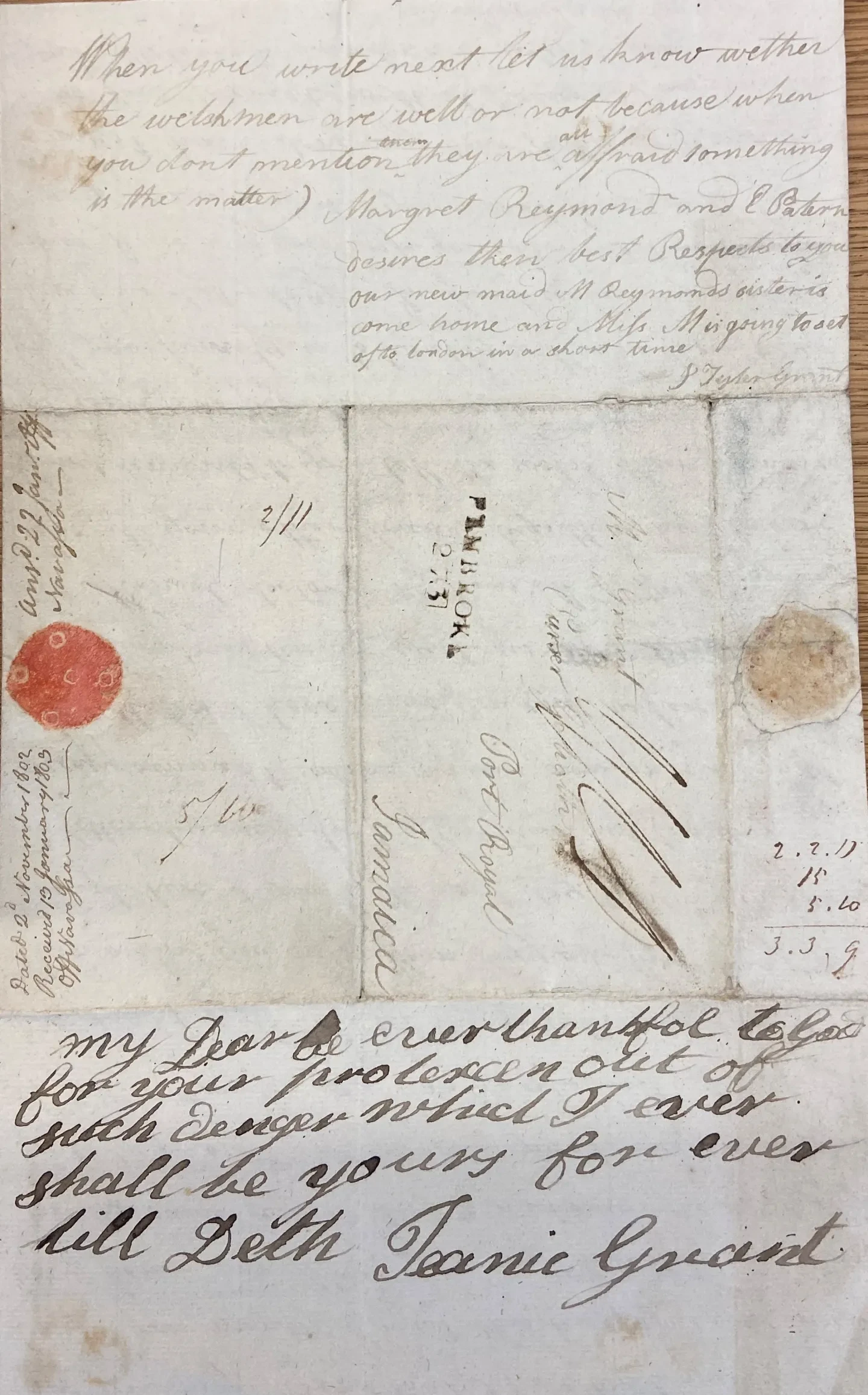

Letter writing was not easily accessible to all. The emotional significance of letter writing is illustrated in the postscript of Julia Grant’s letter to her father, by her mother Jeanie. In noticeably large handwriting Jeanie, who was suffering with poor health and losing her sight, attempted to write a message to her husband. Although only a short sentence could be exchanged, it nevertheless showed the depth of her affection.

Letters could also take long periods to arrive and receive a response. On the back of this letter, Mr Grant, the recipient, notes the date the letter was received and that a response was sent two months later, giving details of the ship that carried it. Some families numbered their letters to help relieve anxiety by knowing they had received them all and none were lost.

Separation

Separation was also experienced at a wider familial level. Some wives of officers joined their husbands when they were posted overseas. Susannah Middleton’s letter reveals the challenges of creating a home away from her family and friends which would only be temporary, as they would be sent by the Navy to new unknown posts around the world. Although Susannah enjoyed being with her husband, an experience many naval wives were not able to have, she did sacrifice spending time with her own family, particularly her ageing parents. Letters and gifts from home were an essential way naval families sustained connections and kept up their morale during periods of homesickness and personal loss.

Widowhood

Life at sea was dangerous and many naval wives faced an early widowhood, bringing new emotional and financial challenges. Henrietta Moriorty’s petition to Admiral John Markham recounts the loss of her husband in the ‘prime of his life’ leaving her with ‘four helpless children’. Her letter actively seeks work as a hospital matron to support herself and family. In the nineteenth century, it was very difficult for women to earn the same wages as men and there were fewer job opportunities for women. Unfortunately, Henrietta was unsuccessful on this occasion, but she was a persistent petitioner as she also wrote directly to the Admiralty. Her second petition is held at The National Archives.

This display was created as part of my curatorial placement undertaken as part of my collaborative doctoral award funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). During this research, I uncovered many personal histories of naval wives and widows which have added depth to the interpretation of popular visual depictions of women left behind on shore.

Royal Museums Greenwich has a rich collection on the histories of male naval officers and seamen, including portraits, uniforms, and personal papers. Although women are less visible, manuscripts reveal that behind every man were mothers, wives, and children who were an essential part of his story and success.

Lone Women and the Royal Navy will be on display until March 2023.