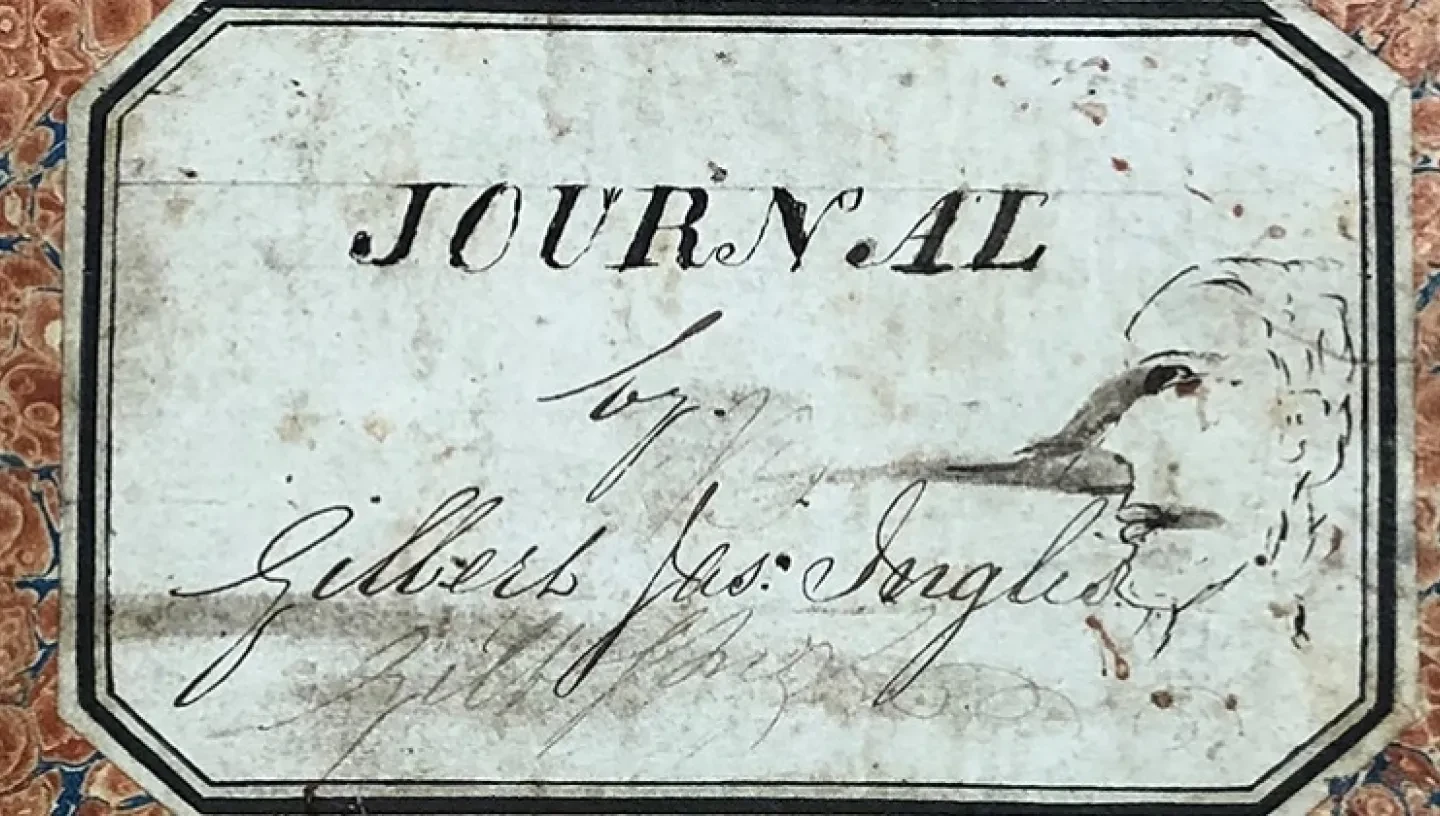

October's item of the month is a personal journal written by Gilbert James Inglis. He served as purser on board the convict ship Duchess of Northumberland and kept a diary on a voyage from London to Hobart, November 1852 to April 1853

On board the Duchess of Northumberland were 220 female convicts, transferred there from Millbank Penitentiary. Accompanying them were 34 children who came from workhouses around the country, from as far afield as Gloucestershire and Lancashire, to join their mothers.

The journal starts on Tuesday 16 November 1852, as the convicts are brought on board. They are organised into messes on board the ship, which will determine their sleeping and eating arrangements. 'The women', as Inglis refers to the convicts throughout his journal, are in both good spirits and health when they arrive on board:

'The women were very much excited to day they had been kept separate at Millbank and now being all together they made a merry singing and dancing just for the purpose of making noise.'

The women are allowed on deck during the day, but are locked below overnight. They are not allowed to talk with the sailors nor the sailors to them; however, Inglis notes that preventing interaction entirely is not always possible.

The voyage gets underway on Saturday 27 November with the ship casting off its moorings and heading out from Woolwich via Gravesend and Margate. It takes the convicts some time to find their sea-legs. A great many of the women being reported as seasick during the first seven days of the voyage. Although two-thirds of a pound of meat and bread are allowed per person per day, by Wednesday 8 December, so many of the women were sick that oatmeal gruel was served to them instead of meat. Weather conditions also caused concern. A gale from Friday 10 – Sunday 12 December caused both sea sickness and a general concern that the heavy swell 'made the women all think that they were going to the bottom'.

During the voyage, prayer services take place and religious tracts are distributed to the women who are prepared to read them. Some of this seems to be part of the psychological control on board to keep the convict’s behaviour in line.

'The matron went through the humane performance of distributing religious tracts to the women (some of them containing accounts of shipwrecks etc. calculated to enliven them at the time).'

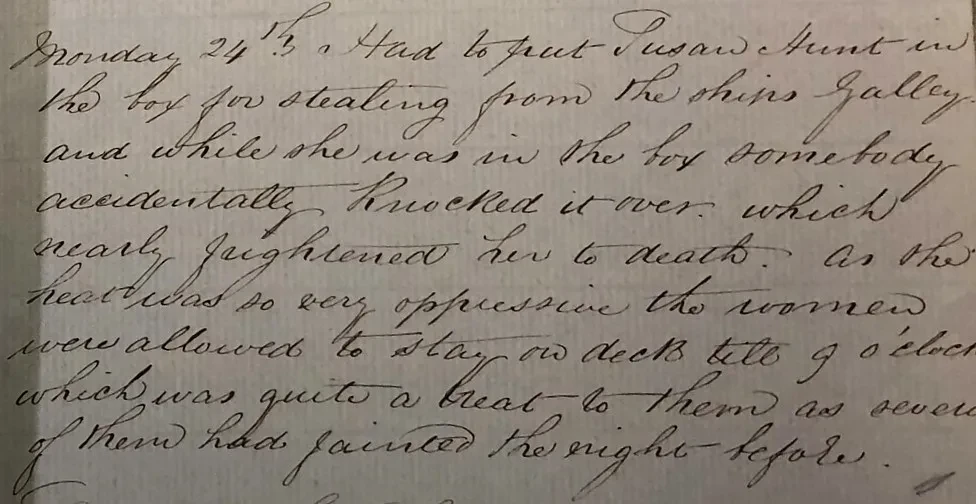

Reminding the convicts of their perilous position was not the only form of control on board. On Saturday 20 November, before the ship departs, Inglis introduces us to The Box, a place for solitary confinement for the convicts who commit misdemeanours during the voyage:

'The doctor rather frightened the women into a quieter mood by putting them in mind of the solitary confinement box, which is a box about six feet high by about two feet square just so as they can stand upright in it.'

Through the course of the voyage, The Box is used to punish those who have fought with other convicts, including the case of Ann Jones, who was confined on Monday 13 December for hitting a fellow convict with a tin and Mary Kelly, who was restrained for quarrelling. Inglis describes her as 'a nasty little cat always quarrelling with someone'.

General insubordination could also lead to time in The Box. Charlotte Thaw is confined for using 'insulting language towards the second mate' and on 11 January, Inglis tells us:

'Jane Nottingham the ugliest woman I ever saw (her age I believe is 26 but you would take her for fifty) was put in the box for insulting language and disorderly conduct. She has been confined in 29 different jails and I believe her last offence was setting fire to a haystack.'

The Box was also used to punish those who stole from the ship’s provisions, such as Mary Murphy, who stole fresh meat shortly before departure, Mary Dunne, who stole a bottle of rum from the boatswain on 22 December and Susan Hunt, who was confined on 24 January for stealing from the Galley. Susan discovered that The Box could be a dangerous place, as someone knocked it over whilst she was inside, 'which nearly frightened her to death'!

In general, however, discipline on board the ship appears to be well maintained, as are the living conditions on board.& In an entry from 6 January, Inglis notes that:

'the women take a great deal of pains in keeping their mess places clean which makes them so much better than emigrants who will never clean unless they are forced.'

In addition to the cooking, cleaning and washing that make up daily life on the voyage, the women are provided with work to undertake, making shirts and knitting. Gilbert rather cheekily muses:

'I wish I had thought to bring away some worsted and I might have had any quantity of stockings made.'

Early on in the voyage, there are a few accidents with one child accidentally drinking chloride of zinc on 7 December and another breaking their thigh bone on 19 December. As the voyage continues, however, there are more cases of sickness. On 21 January, Inglis notes the first death in his journal, a thirteen-month-old child, E.A. Walby. In the following six weeks, a further four children and two of the female convicts die. On 11 February, Inglis records:

'Ann Jones aged 42 departed this life at 10 o’clock to day. Jane Nottingham is in a very dangerous condition. It is strange that both of these women very unwilling to come in the ship and have been very troublesome all the time that they have been on board both to the other women and to the matron.'

Jane Nottingham died the next day. As he notes the death of 2-year-old Henry Mcavoy on 22 February, Inglis bemoans that 'This looks more like a register of deaths than a journal'.

Like many of us who start to keep a diary, the author begins with the best of intentions. His early entries provide details of the daily shipboard routine and weather observations. As the voyage continues, however, entries become shorter and less frequent. On Friday 7 January, Inglis notes that 'the time is getting monotonous'. Monday 10 January is the first day of the voyage for which there is no entry.

His accounts of why women were confined to The Box even become less detailed, with Bella McKay noted as being 'put in for something telling stories, I think' on 24 February. The behaviour of the convicts is also becoming less noteworthy as the crew adapts to them:

'We are getting more used to the squabbles now and so I don’t mention them but they were quite a novelty at first.'

By March, entries in the journal are very infrequent, with only five entries for the month. There is then a large gap after 18 March until 11 April. The 11 April entry is a heartening update about life on board. This turns out to be the penultimate entry and the last in which we are told much of what is occurring:

'The women do not feel the motion of the ship so much as they used to but come on deck in all weathers. Some of them work very hard helping the cooks and hauling the water up and any little jobs that they can do.'

The following day, Saturday 12 April 1853, is the final entry: 'Nearly calm. Had a good clear-out down below. The journal then abruptly stops.

Gilbert Inglis’ journal provides a fascinating insight into part of the daily life of a convict transport vessel and also into the lives of women at sea, whose experiences would otherwise be unrecorded – even if the account is not written from their perspective. It makes us consider - what would the journal of Jane Nottingham contain? It also shows the difficulty of maintaining the discipline of writing an entry every day, even when everything going on around seems so routine and unworthy of record.

Inglis's is not the only account of the voyage of the Duchess of Northumberland that survives. The surgeon’s log for the voyage, which corroborates some of the details of the deaths on board, is kept at The National Archives.

By Gareth Bellis, Archive and Library Manager