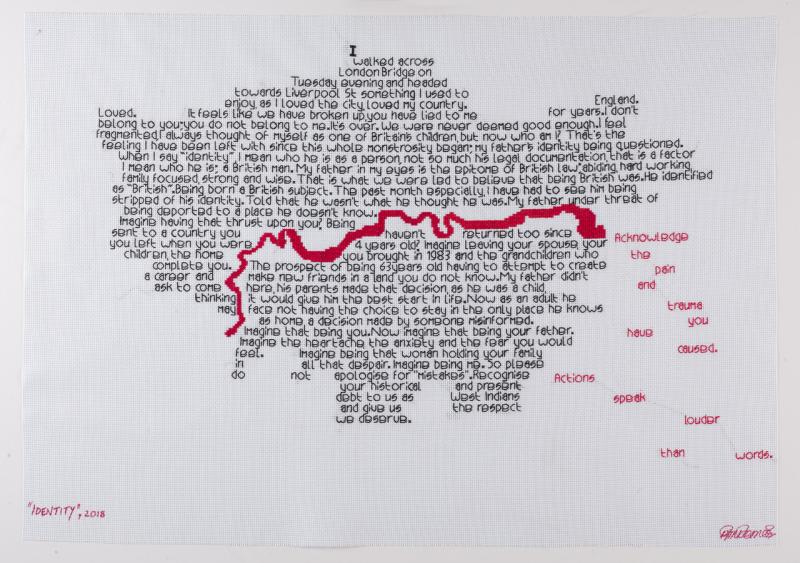

Learn more about the afterlives of slave ships with Dr Richard Anderson

Following the abolition of the slave trade by Parliament in 1807, the Royal Navy intercepted hundreds of slaving ships in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The vessels were tried before Vice-Admiralty and Mixed Commission Courts, and the enslaved people on board legally emancipated. Under various bi-lateral treaties, the vessels themselves were sold at public auction.

The Afterlives of Slave Ships project, the subject of a Caird Research Fellowship that I am currently undertaking at Royal Museums Greenwich, traces hundreds of auctions by British officials and the subsequent histories of intercepted vessels.

Auctioned slaving vessels saw a number of afterlives: as slaving ships, naval vessels, colonial schooners, and in merchant vessels engaged in forms of ‘legitimate’ commerce along the West African coast. Royal Naval captains purchased several vessels, likely those that they found most seaworthy and useful additions to a West Africa squadron that rarely included the Navy’s best vessels.

The Brazilian brig Henriquita, built in a Baltimore shipyard, entered naval service after being purchased and renamed as the Black Joke (image above). The vessel gained a level of fame as by far the navy’s fastest and most effective vessel on the West African coast, allowing its crew to intercept many vessels from 1828 to 1832. When the Black Joke was scrapped in 1832 due to the deterioration of its timbers, naval crews took pieces of the vessel to create their own mementos of the West Africa Squadron’s most effective vessel.

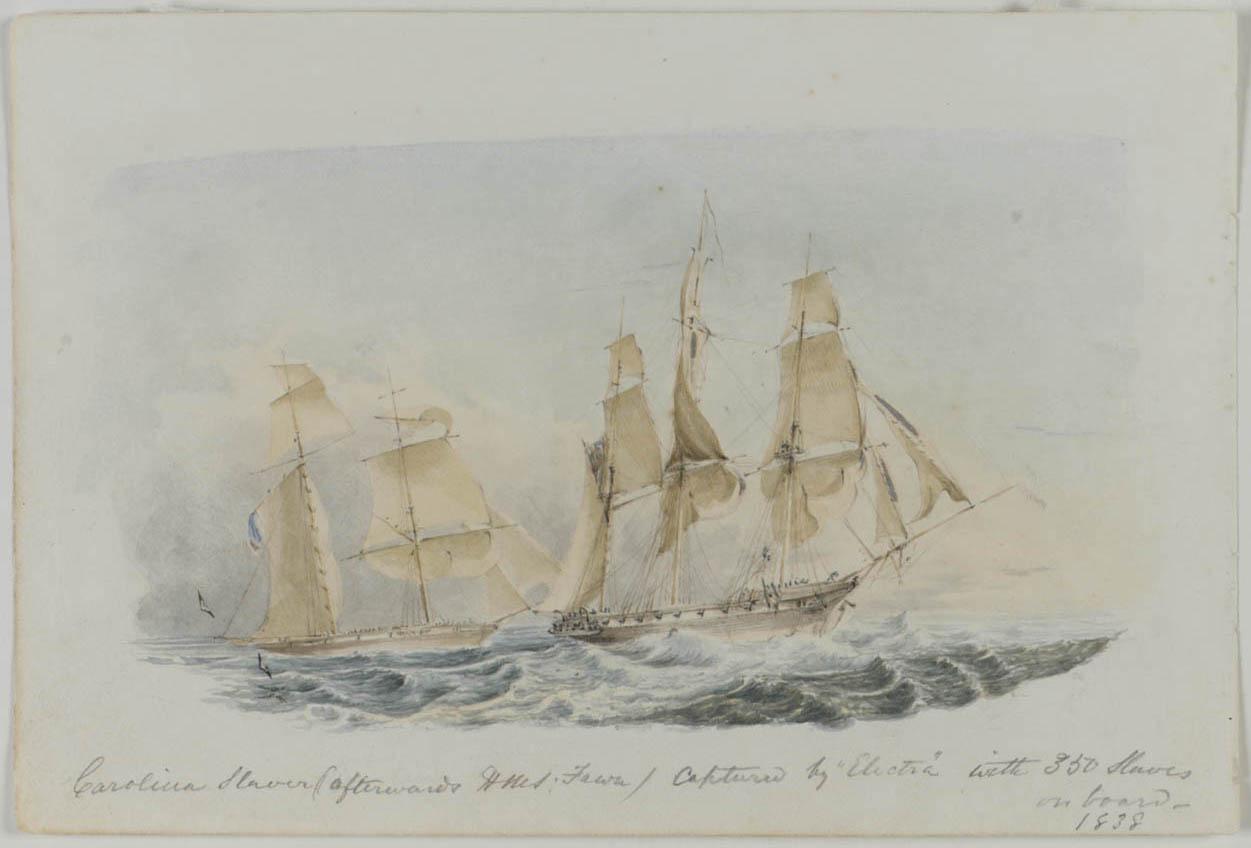

As paintings of naval vessels and the squadron’s operations against slaving ships became a common genre, we have today several images of former slaving vessels in their new role as naval ships and slave trade suppressors.

Examples of former slave vessels in the collections of the National Maritime Museum include the abovementioned HMS Black Joke, formerly Henriquetta (PAH8175); the HMS Fair Rosamond, formerly the slaving ship Dos Amigos (PAH5778); and HMS Fawn, formerly the slaving ship Carolina (ZBA2716) which was condemned by the mixed court at Rio de Janeiro in 1839 and became the fastest cruising vessel on the Brazilian coast.

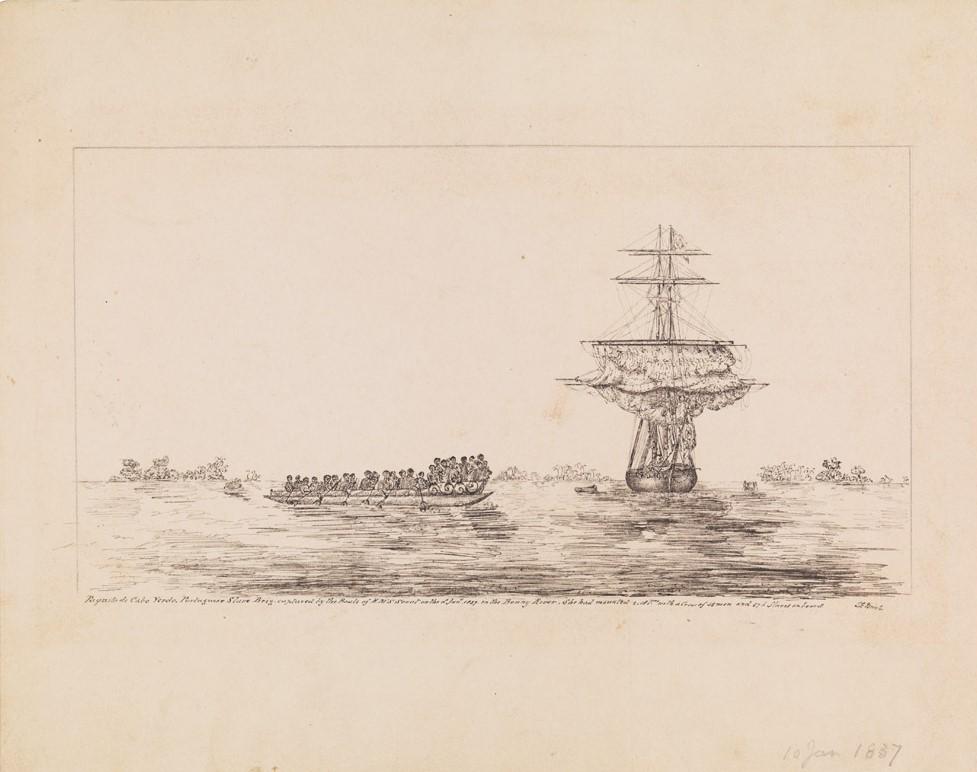

Other vessels re-entered the slave trade, often under a new name and flag. The image below shows the boats of HMS Scout capturing the Portuguese Brig Paquete de Cabo Verde in the Bony River with 576 enslaved Africans on board. John Dean Lake, a Sierra Leonean trader, purchased the vessel for £825 at auction in Freetown. Lake allegedly resold the vessel to Miguel Bertinote, an agent of Pedro Blanco.

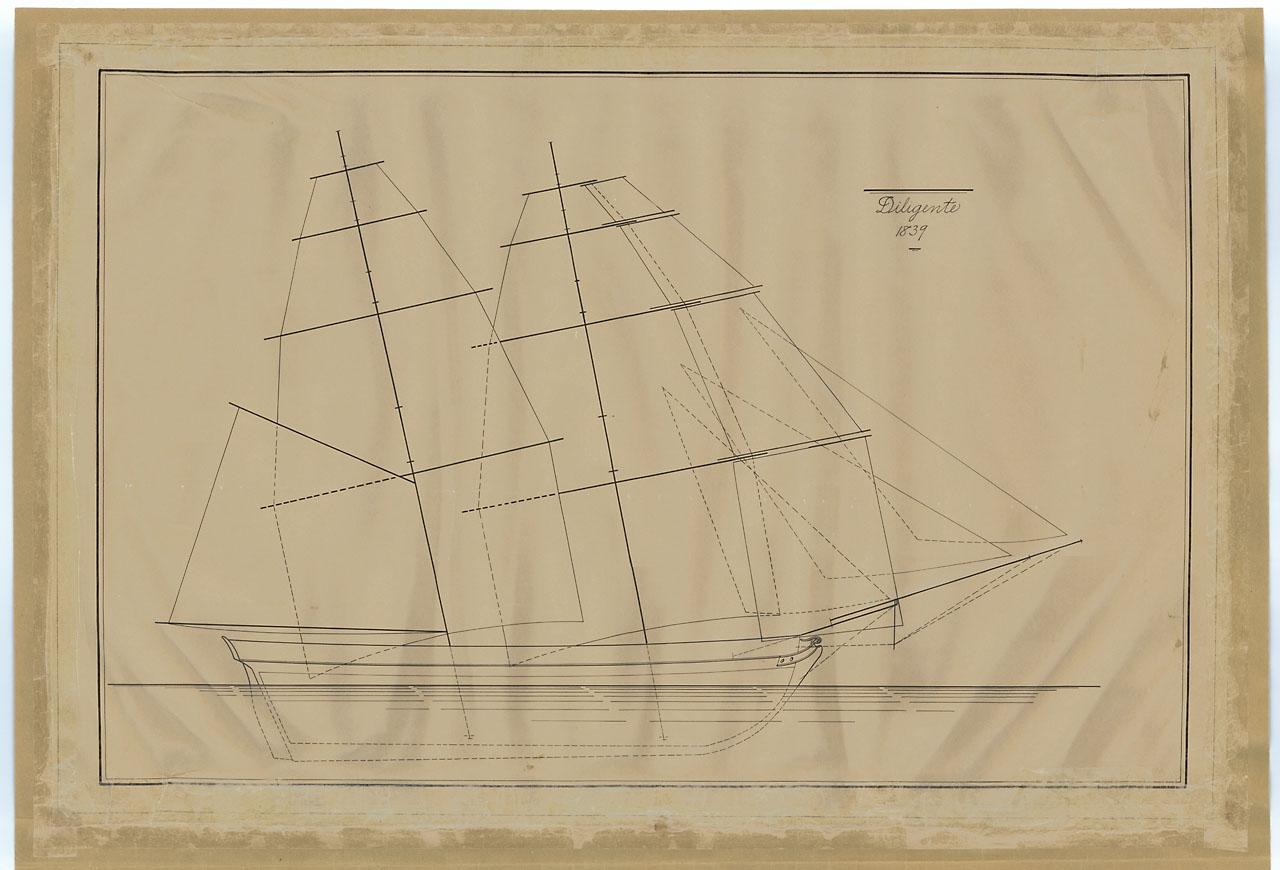

Bertinote personally sailed the vessel out of Freetown Harbour under Spanish colours, first to Havana and then Cadiz, where it was renamed Diligente (ship plan below). The sketch drawing of the Paquete de Cabo Verde and ship plan of the Diligente are thus of the same vessel under different names. When the crew of HMS Brisk captured the Diligente off the Gallinas in August of 1837, the vessel was again taken to Freetown and condemned for the second time in a year. The vessel was broken up under a ‘break-up clause’ which the British inserted into bilateral treaties in order to prevent ships re-entering the slave trade.

With time Liberated African entrepreneurs pooled money to purchase their own vessels. Many used them to return to their regions of birth, using the former ships of the slave trade to reverse the middle passage. Others repurposed the timbers of broken up vessels.

At St. John’s Maroon Church, founded in Freetown in 1808, the roof and several of the pews were constructed from the wood of a broken-up slaving ship. Slaving ship auctions reflected both the limitations of British slave-trade suppression on the West African coast and the ingenuity of formerly-enslaved people in building community and commerce by bidding for intercepted vessels.