In this blog we explore some of Austen’s literary nautical themes, but also consider her actual maritime connections.

Readers of Jane Austen's novels will be familiar with her naval references. Less well-known is that two of her brothers served and became admirals in the Royal Navy. Some of Francis and Charles Austen’s papers are held in the Archive of the Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum.

To mark the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth, there will be a small display of Austen-related archival material at Royal Museums Greenwich. I've also updated this blog post (first published in 2023), to explore some of the nautical themes in Austen's novels, and the naval careers of her two brothers which helped shape two of her best-loved novels.

Jane Austen’s maritime connections

Jane Austen was born on 16 December 1775 in Hampshire and began writing in her teens. For nearly all her adult life, England was at war with France; two of her brothers enjoyed naval careers during this transformative period in British maritime history.

Jane was in almost constant written communication with them while they were away at sea. When they were not, Jane paid extended visits to her brothers and their families, meeting their many naval acquaintances.

We know that, like practically all British people of any means at the time, the Austens had numerous family connections with the transatlantic slave trade. Austen's father, Rev. George Austen, was a trustee for an Antigua sugar plantation; Jane's aunt, Jane Leigh Perrot, was born into a wealthy family of enslavers in Barbados.

As Royal Navy officers, Jane's brothers were involved in the maintenance of the transatlantic slave trade underpinning the 'colonial system' largely before 1807. Following the abolition of the slave trade, they undertook patrolling/interception work.

Furthermore, Jane lived in Bath for three years, only 11 miles from Bristol, the busiest British port in the transatlantic slave trade until Liverpool took over in the mid-18th century.

Jane was well-informed and passionate about the national issue of abolition; she wrote to her sister, Cassandra, saying she was 'in love with' Thomas Clarkson, a prominent campaigner against the slave trade and the author of The History of the rise, progress and accomplishment of the abolition of the African slave-trade by the British Parliament (PBB3495/1-2).

Jane died in on 18 July 1817, in Winchester. The event was recorded by her brother Charles, in his diary on 20th July (AUS/109).

Only four of Jane’s novels were published during her lifetime and she received little acclaim or financial reward. Now, however, she is considered one of the greatest writers in the English language. According to her nephew, 'with ships and sailors, she felt herself at home' which I believe is clearly demonstrated in two of her novels.

Maritime themes in Mansfield Park

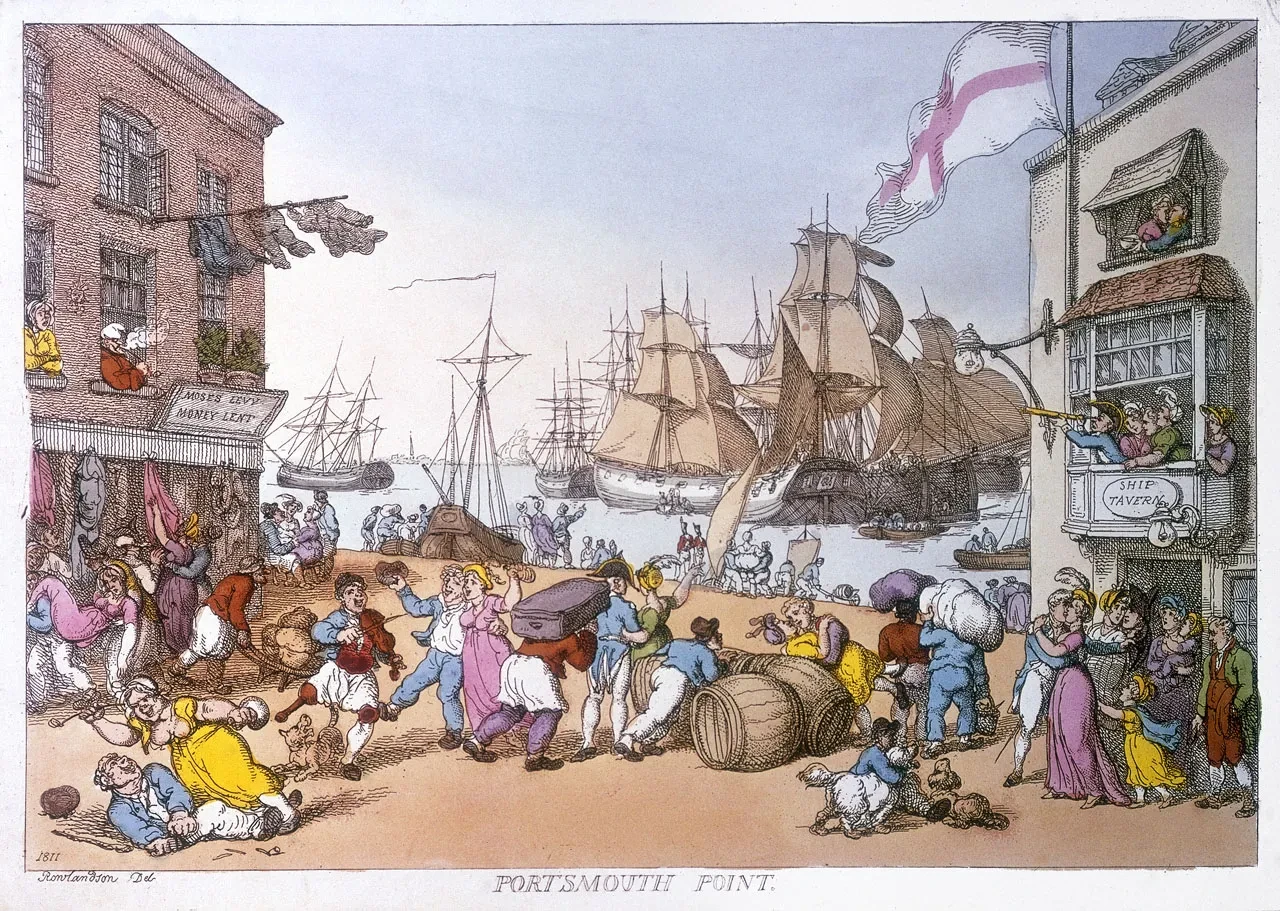

In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price is the eldest daughter in an impoverished naval family struggling to survive on half pay, in Portsmouth, the Navy’s largest and most important base.

Fanny is adopted by rich relatives, the Bertrams, and transported to the opulent surroundings of Mansfield Park. It becomes apparent as the novel progresses that Sir Thomas Bertram has a sugar plantation on Antigua, which he visits off-stage, for part of the novel. On his return, the 'dead silence' (see Mansfield Park, page 155) that greets Fanny’s questioning of her uncle about the slave trade has been poured over.

Does the silence reveal the Bertrams’ collective guilt at the fact they owe their elegant lifestyle to the exploitation of enslaved people? Or are they just completely disinterested in the distant plantation which ‘pays the bills at MP’? Are we blowing a passing reference out of all proportion? Or is Austen’s meticulous attention to detail such that every reference, however small, is meaningful?

The very name of ‘Mansfield’ has loaded connotations with the Earl of Mansfield and the Zong case, and would have been clearly recognized by her 19th-century readership. 'Norris', the name of Fanny’s awful aunt, is shared with a notorious contemporary pro-slavery campaigner.

The issue will no doubt continue to be debated because of Sir Thomas’ silence. Significantly, Austen’s most famous mention of enslavement is in the form of an unanswered question; she leaves it hanging, inviting debate and discussion.

We learn about Fanny’s beloved brother William’s naval career. We experience her anxiety about having a relation away at sea for years on end and feel William’s frustration at failing to advance from midshipman, through lack of connections, after seven years of service.

We are introduced to Mary Crawford who, through her admiral uncle, is accustomed to socialising among the highest (although possibly not the most moral) ranks of the Navy, with 'their bickerings and jealousies … Of Rears and Vices, I saw enough' (see page 48).

When William visits Mansfield, his nautical tales enthral everyone. Through Crawford connections, the patronage system is worked to finally promote William to lieutenant, leaving Fanny under obligation to an unwanted suitor: Mary’s brother, Henry.

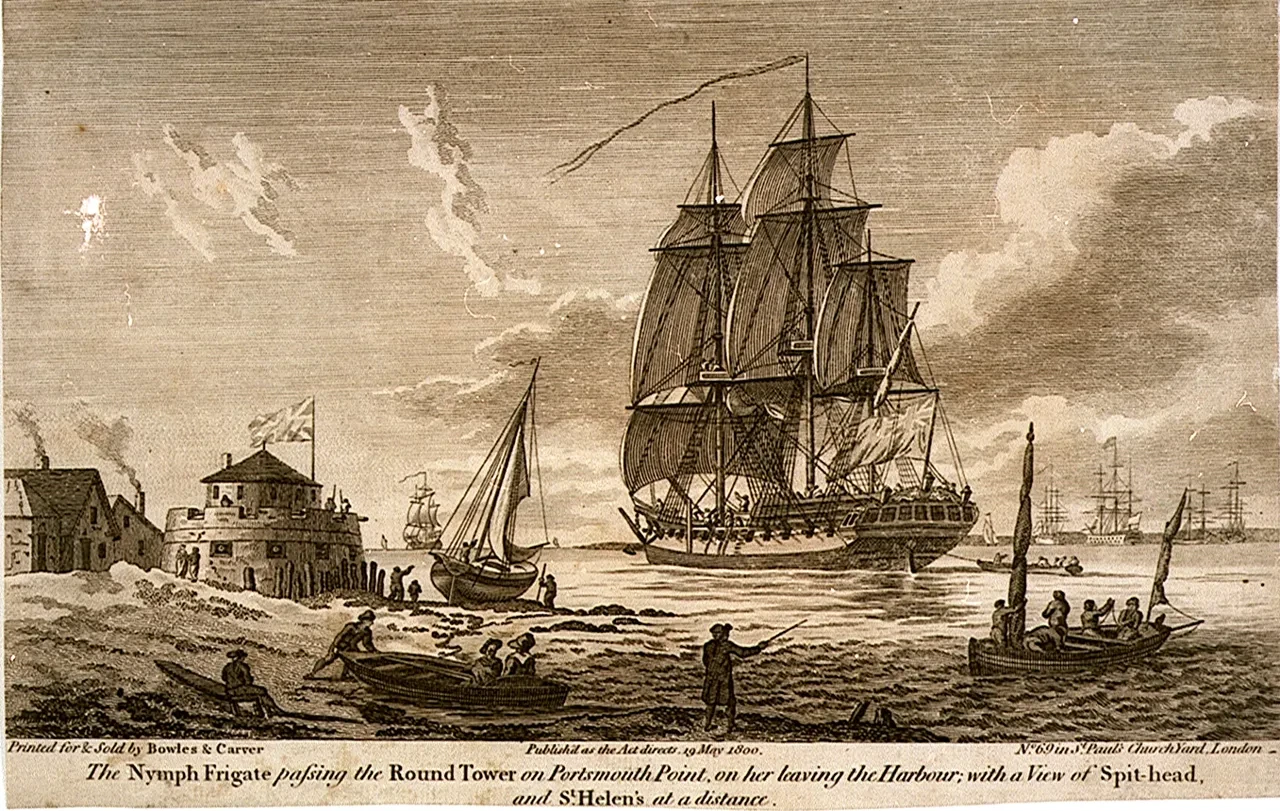

Accompanied by a jubilant William, Fanny returns to Portsmouth in disgrace, for refusing Crawford. When the latter visits Fanny and her family to renew his wooing, he is caught up in the excitement and pride of the naval dockyard, which he has visited ‘again and again’ (see page 316). We share Fanny’s anguish at premature separation from William, as he rushes off to join his ship, the Thrush, at Spithead.

We hear on the last page of the novel of William’s ‘continued good conduct and rising fame’ (see page 371).

The Navy in Persuasion

Persuasion is set in 1814, at the (temporary) cessation of the French wars. Austen explores how 'this peace will be turning all our rich Navy Officers ashore. They will be wanting a home … Many a noble fortune has been made during the war' (see Persuasion, page 20).

Some consider these maritime returnees as an attractive marriage prospect, but others, such as Sir Walter Elliot, view the Navy negatively as 'the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dream of' (see page 22). He also objects to the effect such a life has on sailors’ appearances; 'they are all knocked about, and exposed to every climate, and every weather, till they are not fit to be seen' (see page 22).

Captain Frederick Wentworth had first met the Elliots eight years before the novel starts, falling in love with Sir Walter’s daughter, Anne. He proposed, but she is persuaded, against her own better judgement, to refuse his offer due to his lack of both fortune and rank.

Anne has since kept an eye on his career through the ‘navy lists and newspapers’, with their tales of ‘successive captures’ (see page 29), and so is fully aware of his accumulated prize money. By the time he returns to England, he is a gentleman of fortune, having been made a commander following the Battle of San Domingo, fighting against the French over control of the riches of the sugar plantations.

The novel explores many maritime topics, some positive, and some less so. The first words Anne speaks are in defence of the Navy:

The navy, I think, who have done so much for us, have at least an equal claim with any other set of men, for all the comforts and all the privileges which any home can give. Sailors work hard enough for their comforts, we must all allow.

Persuasion, page 21

There is the issue of surviving on half-pay when without a ship, which became an increasing problem and was widely discussed at the time, resulting in 1814 in a new peacetime pay scale. We are also given insights into what effect a naval career can have both on those in service and those remaining at home.

Mrs Croft, possibly based on Charles’ wife, Fanny Palmer, has remained with her husband during their 15 years of marriage, both at sea and at his stations abroad, and declares 'I can safely say, that the happiest part of my life has been spent on a ship' (see page 61).

The importance of prize money (or lack of it) does not only affect Captain Wentworth. Captain Benwick was forced to put off marriage, 'waiting for fortune and promotion' (see page 81), but by the time it came, his fiancée had died. Admiral Croft comments 'these are bad times for getting on' (see page 139), and there is a subtle reminder of the possible dangers a naval career entails, with reference to Captain Harville’s lameness.

While Louisa Musgrove and her sister ‘burst forth into raptures of admiration and delight on the character of the navy … of sailors having more worth and warmth than any other set of men in England’ (see page 83), there is also their mother’s grief at the death of her midshipman son, at sea.

As Anne and Wentworth rediscover their love for one another, and Anne herself becomes a naval wife, the novel closes with even the narrative voice showing a strong bias towards the Navy:

His profession was all that could ever make her friends wish that tenderness less, the dread of a future war all that could dim her sunshine. She gloried in being a sailor’s wife, but she must pay the tax of quick alarm for belonging to that profession which is, if possible, more distinguished in its domestic virtues than its national importance.

Persuasion, p 203

Sir Francis William Austen (1774–1865)

Sir Francis William Austen’s naval career spanned 79 years, first entering the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth, in 1786. The display includes Francis’ mathematical workbook from the two years he studied there (AUS/14, on display December 2025 – March 2026).

Jane’s brothers were both helped in their early naval careers by family connections. Their older brother James and their cousin (another Jane) both married into influential naval families. Rapidly promoted to midshipman within ten months, Francis gained immediate commission, being appointed lieutenant of an armed brig, the Dispatch, in 1792, unlike the frustrated William Price in Mansfield Park.

Use of a further family connection meant that in early 1805, Francis was posted to the Canopus, and accompanied the Victory across the Atlantic and back, in search of combined French and Spanish fleets, before joining the blockade of Cadiz.

Francis was then sent by Nelson to Gibraltar, to collect provisions, despite his pleas to remain and face the imminent engagement. Nelson assured him he would be back in time for the battle, but this was not to be. As a result, Francis was absent from the Battle of Trafalgar, which was of lifelong disappointment to him. He had no connections or leverage with Nelson’s replacement, Collingwood, and had to put off marriage, having missed out on prize money.

On display until March 2026 are Nelson’s plan or ‘Order of battle’ for what would be the Battle of Trafalgar, showing the Canopus as the leading ship (AUS/17/1).

The following year, however, Francis did gain recognition and reward (like Captain Wentworth) at the Battle of San Domingo, still onboard the Canopus. He then remained in active (albeit mundane) service almost continuously until the end of the Napoleonic Wars, including escort duties to India, China and in the Baltic.

In a letter home, in 1808, Francis left no doubt about his views on enslavement:

slavery however it may be modified is still slavery, and it is much to be regretted that any trace of it should be found to exist in countries dependent on England, or colonized by her subjects...

Francis Austen, 1808

During the writing of Mansfield Park (1812-1814) Jane wrote to Francis for information about naval vessels and to request that she might use the names of the ships in which he (and his brother) had served. She mentions four ships in the novel with Austen connections - the Elephant, which Francis was commanding in the Baltic at the time, the Canopus, the Endymion, in which his brother Charles served three times, and the Cleopatra, in which Charles sailed home in 1811.

Over the next three decades, Francis was regularly promoted but he did not actually return to sea until 1844, at the age of 71. His final posting was as Commander-in-Chief of the North America and West India Station. In 1848, he then came home to Portsmouth and continued to be promoted, finally becoming Admiral of the Fleet in 1863, two years before his death. Three of his sons entered the Navy.

Charles Austen (1779–1852)

Charles followed his brother into the Royal Naval Academy in 1791. His first commission was in his cousin’s ship, the Daedalus. In 1797, he was promoted to lieutenant for his part in the Battle of Camperdown.

In 1800, Charles was a lieutenant on board the Endymion, when it captured the French ship Le Scipio. He used the resulting prize money to buy Jane and Cassandra gold cross pendants set with topaz; in Mansfield Park, Fanny’s beloved brother William gives her ‘a very pretty amber cross’ when he returns from seven years away at sea.

On display until March 2026 is the lieutenant’s logbook from the Endymion, recording the capture of the Scipio on 8 May 1800 (ADM/L/E/106).

In 1804, Charles was then made commander, following a series of engagements including the capture of three men-of-war and two privateers. He then spent almost seven years patrolling the Eastern seaboard of North America, before returning to England in 1811.

Following Napoleon’s escape from Elba, Charles was sent first to pursue a Neapolitan Squadron said to be in the Atlantic; then to aid the blockade of Brindisi; and finally to suppress piracy off Greece. This all occurred before his ship, the Phoenix, was wrecked - fortunately without loss of life. Despite being cleared of any error or negligence, Charles then struggled to find another command. He did not go back to sea for a decade, having to survive, with his increasing family, on half pay.

Charles was then stationed in Jamaica, before an accident in 1830 forced him to return home for another eight years, prior to being promoted to rear admiral in 1846 for his contribution in the bombardment of Acre. In 1850, he was made Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies and China Station, where he led the capture of Rangoon in 1852, before dying in the line of duty, of cholera. His two sons both entered the Royal Navy.

The Austens at Royal Museums Greenwich

There will be a small display of some Austen-related archival material, outside the Caird Library, in the Sammy Ofer Wing of the National Maritime Museum until March 2026.

Sadly, none of Jane Austen's notebooks or diaries have survived. Most of Jane's letters to various family members were destroyed by her relatives, which I think makes our archival holdings even more precious.

Francis’s papers (AUS/1-17) were presented as a gift to the National Maritime Museum by Captain Ernest Leigh Austen in 1930. They cover almost all his active service and include official logbooks, letter books, order books, and loose papers, which mainly comprise general remarks and notes.

Charles’s papers (AUS/101-163) contain a complete series of diaries that he kept between 1815 and 1852, which were deposited at the Museum as a private loan in 1962.

You can request to view the items, not on display, in the Caird Library Reading Room. For further information on this subject, we have the following titles within the Caird Library:

- Hawkridge, Audrey. Jane and her gentlemen: Jane Austen and the men in her life and novels. PBF2800.

- Hubback, J H. Jane Austen's sailor brothers: being the adventures of Sir Francis Austen, GCB, Admiral of the Fleet, and Rear-Admiral Charles Austen. PBD5049.

- Johnson Kindred, Shelia. Jane Austen's transatlantic sister: the life and letters of Fanny Palmer Austen. PBH8332.

- Kaufmann, Miranda. Heiresses: marriage, inheritance and Caribbean slavery. PBK1576.

- Looser, Devoney. Wild for Austen: a rebellious, subversive, and untamed Jane. PBK1630.

- Southam, Brian. Jane Austen and the navy. PBF0267.

The Caird Library is open Tuesday–Friday, 10.00–16.45. Please note, the Caird Library and Archive will be closing at 4.45pm on Thursday, 18 December 2025 and will re-open at 10.00 on Tuesday, 6 January 2026.

References

Please note that all references relate to the following editions: Mansfield Park (Oxford University Press, 2008) and Persuasion (Oxford University Press, 2004).