Migration has been and continues to be an intrinsic part of the human experience, with people leaving their homes for political, environmental, social and economic reasons.

This collection of National Maritime Museum objects showcases the achievements made, struggles endured and the identities of refugees who have been forced to leave their homes.

Every year Royal Museums Greenwich joins communities and organisations from across the UK to mark Refugee Week. The arts and culture festival takes place in June; find out more about our events and displays here.

Explore the collection

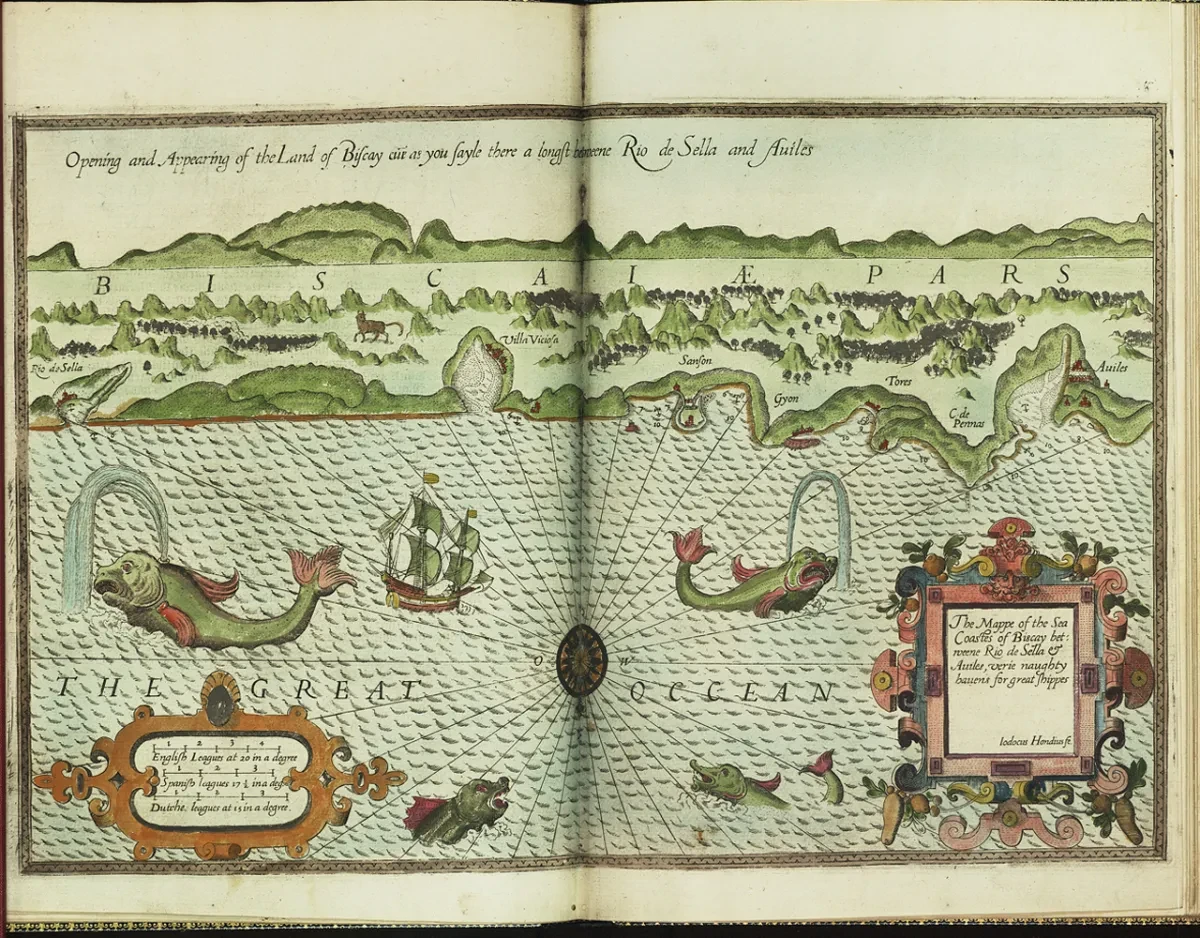

The mappe of the sea coastes of Biscay betweene Rio de Sella & Aviles, 1588

This sea atlas was published in London and was engraved by a highly skilled artisan, Jodocus Hondius, who arrived in England from Ghent in 1583-84 as a refugee.

16th-century Europe was wracked by religious conflict which led to the displacement of a huge number of people.

In England, Hondius settled in Southwark. Already an engraver of some renown, he cut type and worked on maps and portraits. Hondius brought engraving skills with him to England and engraved not only several of the plates in the sea atlas, like that pictured here, but also the plates for what are recognised as the earliest English globes, two of which are now at the Middle Temple library.

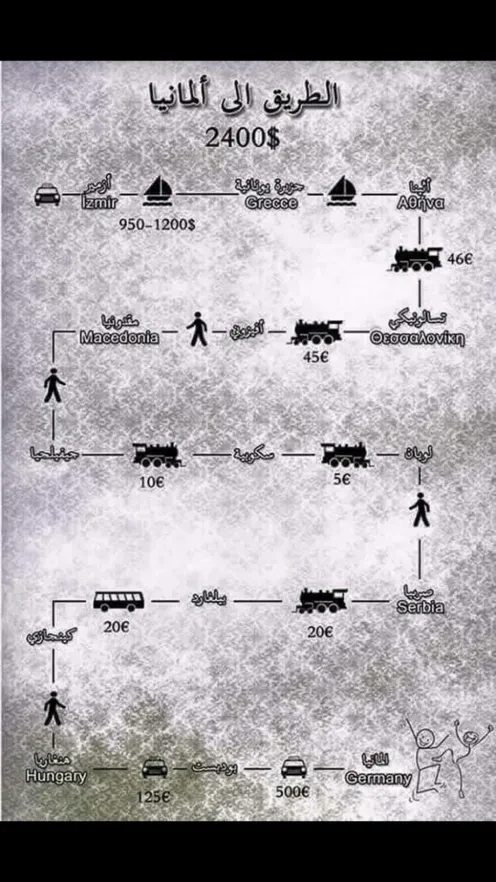

The Road to Germany, circa 2015

This map depicts different stages of a route from İzmir in Turkey to Germany, which was one of the main routes to Europe used by refugees from Syria and the Middle East in 2015. It is a diagrammatic representation of the so-called Western Balkan route – from Turkey to Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary and into Western Europe.

Each stage of the route is represented by a graphic depicting the relevant mode of transport, accompanied by the likely cost and the currency. The destination is marked with two dancing stick figures.

In 2015 this map was frequently exchanged over WhatsApp and other social media applications between Arabic-speaking refugees. The map is an example of the sort of ephemeral information people can end up relying on if a journey they are making is deemed illegitimate.

When border fences in Hungary were erected in late 2015 and early 2016, the route as depicted in this map became less relevant to those trying to reach Europe.

Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich by Jacques Joseph (James) Tissot, 1878

Artist Jacques Joseph (James) Tissot fled to London in 1871 following his involvement in the Paris Commune – a short-lived radical government.

He became known for his images of fashionable London life, such as this depiction of the much-loved Trafalgar Tavern in Greenwich. Three bare-footed children can be seen mud-larking on the Thames river foreshore, looking up at figures sat in the balcony above.

Cumbrian Blue(s) Refugee Series No: 7 by Paul Scott, 2022

In May 2016, a fishing vessel carrying 562 passengers ran into difficulties off the Libyan coast. As a search and rescue team approached, the passengers moved across the boat to access the life jackets being handed out, causing it to capsize. Five people lost their lives.

Artist Paul Scott transfer-printed an image of the incident onto this 19th century platter. A leading figure within the contemporary art world, Scott is known for his subversive ceramics, which repurpose historic tableware to highlight contemporary issues.

Cumbrian Blue(s) Refugee Series No:7 is on display in the Closet in the Queen's House.

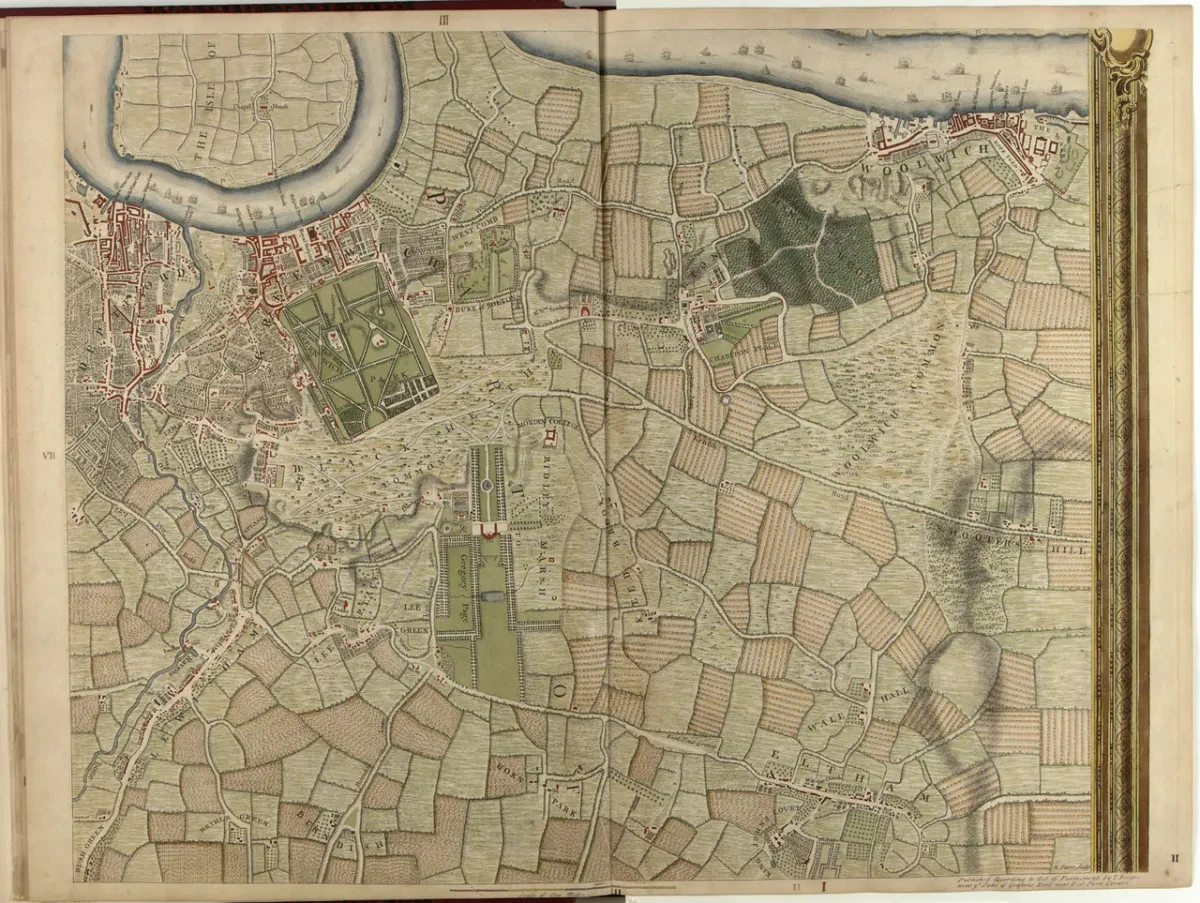

Sheet from ‘An exact survey of the cities of London and Westminster’, by John Rocque, 1746

John Rocque arrived in Britain as a young child in 1709. His parents had left France as Huguenot refugees, going first to Switzerland, where John was born, and then to England.

A talented draftsman and mathematician, he carried out an accomplished survey of London, published in 1746. Consisting of a series of coloured maps, it was the most extensive survey of London made to that date. This map depicts Blackheath and Greenwich.

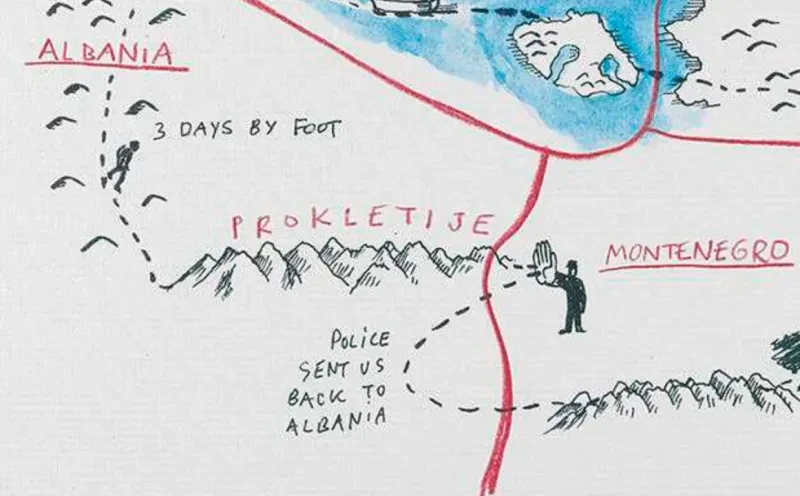

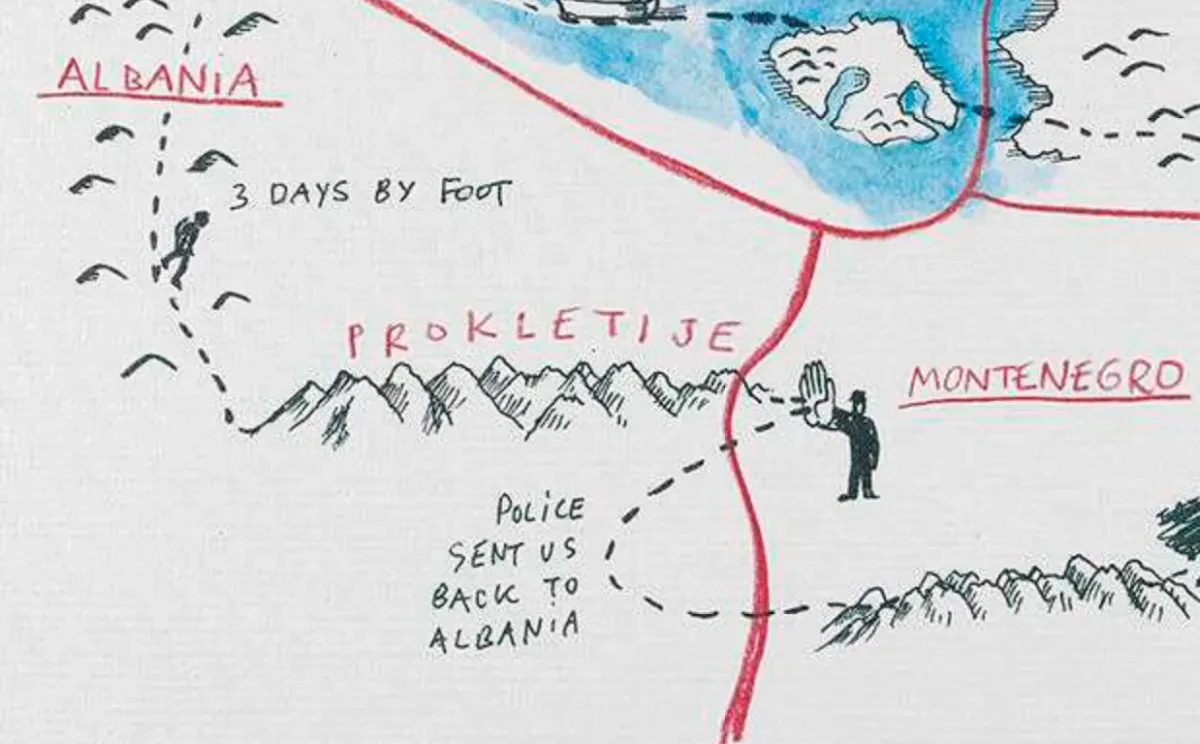

Series of narrative maps documenting the journeys of individual refugees to Serbia by Djordje Balmazovic

These works by artist Djordje Balmazovic are narrative maps, illustrating the journeys made by people who have experienced displacement and the difficulties they faced at heavily policed borders. These people arrived in Serbia from a range of places, including Syria.

This section depicts a journey from Sri Lanka to Serbia, passing through countries including Malaysia, Australia, Turkey, Greece, Albania and Montenegro.

Balmazovic aimed to make the maps as factual as possible, rather than dwell on the suffering experienced. His aim was to highlight the lack of humane asylum policy in Europe.

Portable heliometer by John Dollond & Son, c.1755

John Dollond was the descendant of Huguenot refugees who had arrived in London following the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes (ending religious toleration of Protestants, which had lasted for nearly a century).

He established John Dollond & Son, a company renowned for producing optical and scientific instruments. This portable heliometer was one of the instruments made, and was used for solar observation.

The firm later became Dollond & Aitchison (the retail optician chain), which merged with Boots Opticians in 2009.

Sea Deity by Eve Shepherd, 2017

Sea Deity was made by sculptor Eve Shepherd and local families from Action for Refugees in Lewisham.

Shepherd worked closely with the families to develop a figure that was a ‘timeless protector’, a ‘defender’ and a ‘benevolent, all-powerful being’.

"The kids made their bust wearing armour, with Taser hair, and a water cannon or pepper spray crown," Shepherd explains. "They infused their clay ‘Being’ with the belief that it/they could provide them with food, education, clothing, money, safe travel, community, spiritual belief and family."

These ideas are evident in the final bust which Shepherd sculpted in bronze. The work is currently on display in the Sea Things gallery at the National Maritime Museum.

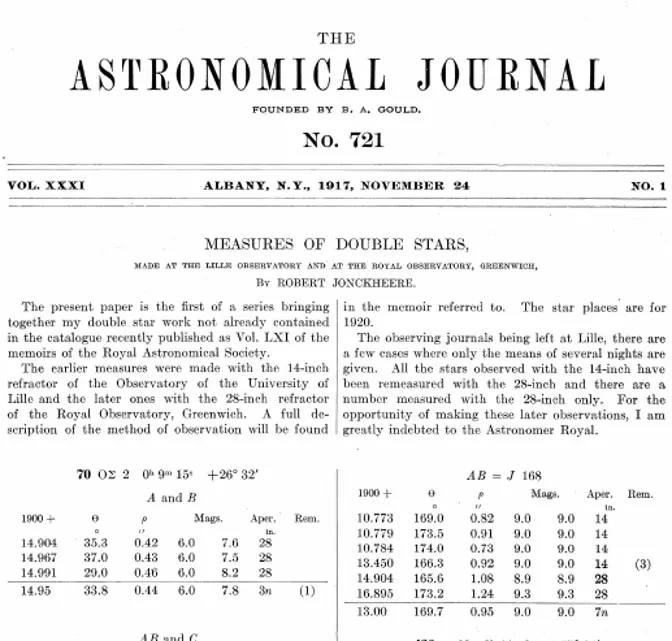

Article by Robert Jonckheere, 1917

During the First World War, the Royal Observatory welcomed astronomer and refugee Robert Jonckheere.

Born in Belgium, Jonckheere later established an observatory at Hem, near Lille. Following the outbreak of war Jonckheere was displaced to England, and started work at the Royal Observatory. This article on his research on double stars was completed during his time in Greenwich.

Jonckheere wrote that he would “never be able to thank Sir Frank Dyson [the Astronomer Royal] and Mr T Lewis [Observatory Assistant] sufficiently for their kindness and support”.

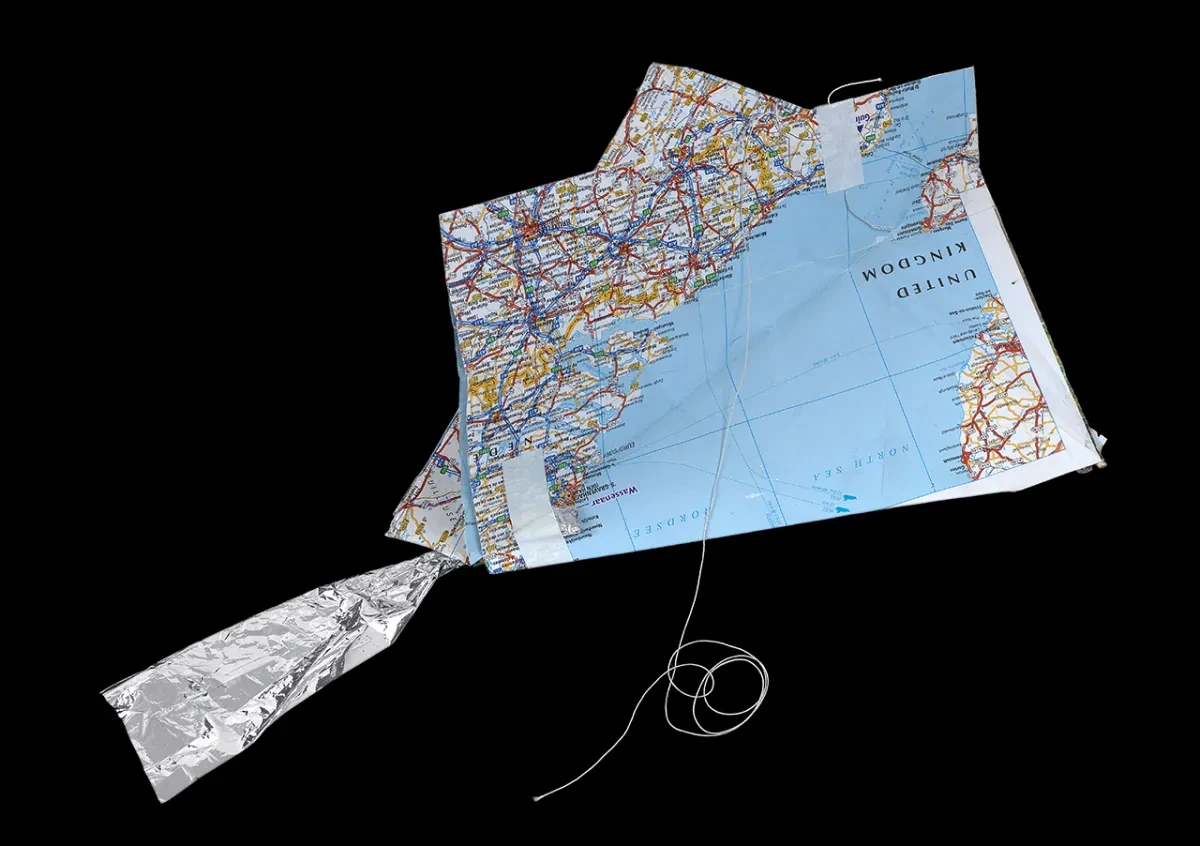

Kite made from a road map, 2016

This kite was made in the Calais camp known as 'The Jungle' in March 2016. It was part of a session facilitated by Art Refuge UK, an art and art therapy organisation which worked with refugees living in the area.

Making use of the limited infrastructure of the camp, Art Refuge UK started to facilitate kite making begun by Afghan residents. As an activity, kite making gave opportunities for play and creativity, problem-solving and working together, in a context where people's traumatic experiences, both past and present, can lead to an acute sense of psychological unsafety.

In March 2016, as the southern part of the camp was destroyed, maps were used to make kites. This was pragmatic, and perhaps also symbolic. Pragmatic, because the maps were readily available – pages from road atlases provided large sheets of robust paper which could withstand the Calais wind. Symbolic, because in a context when people’s movement across borders is prevented, kites can become a symbol of hope (one can still go up, even if not across).

Made from maps, primary expressions of political borders, the kites were perhaps also a symbol of resistance to contemporary border regimes.

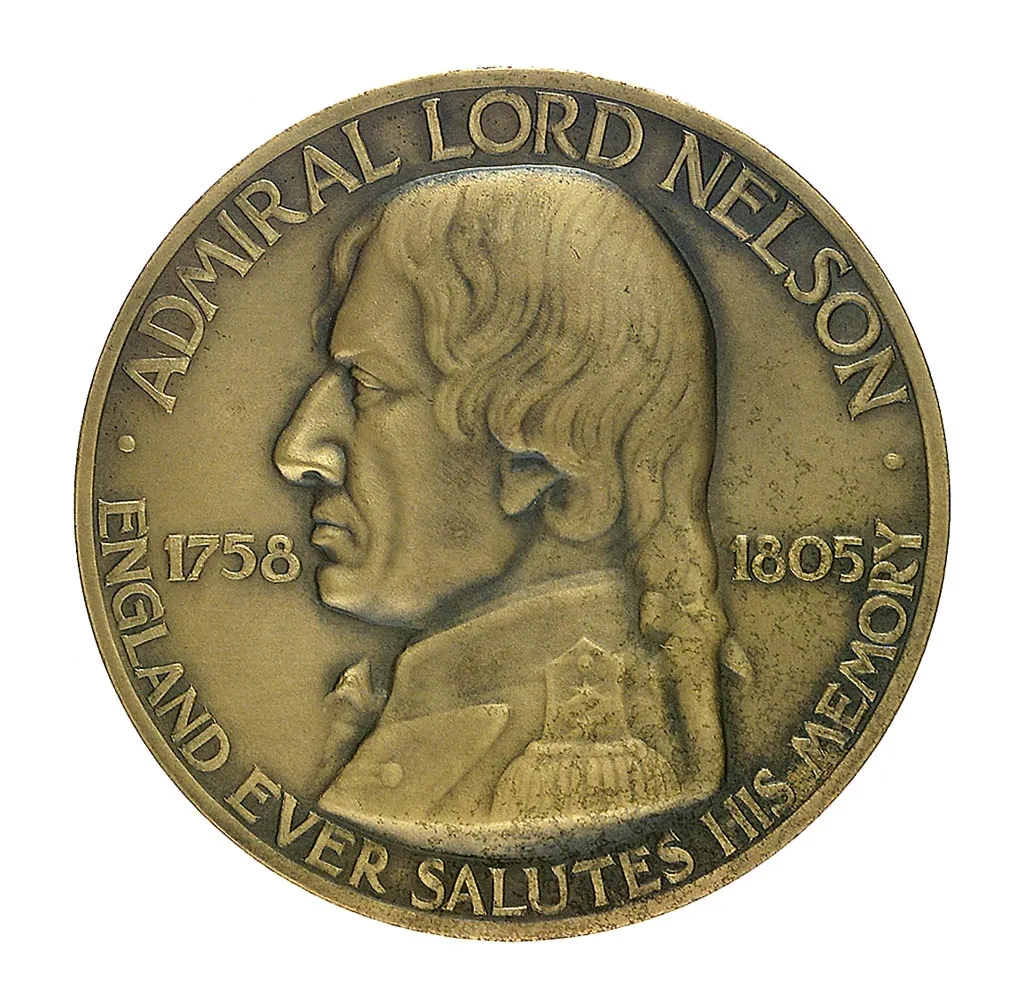

Trafalgar commemoration medal by Paul Vincze, 1955

Paul Vincze, artist and internationally acclaimed medallist, fled Hungary and arrived in England in 1938, where he set up a studio.

He made many commemorative medals, including this one, which marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar.

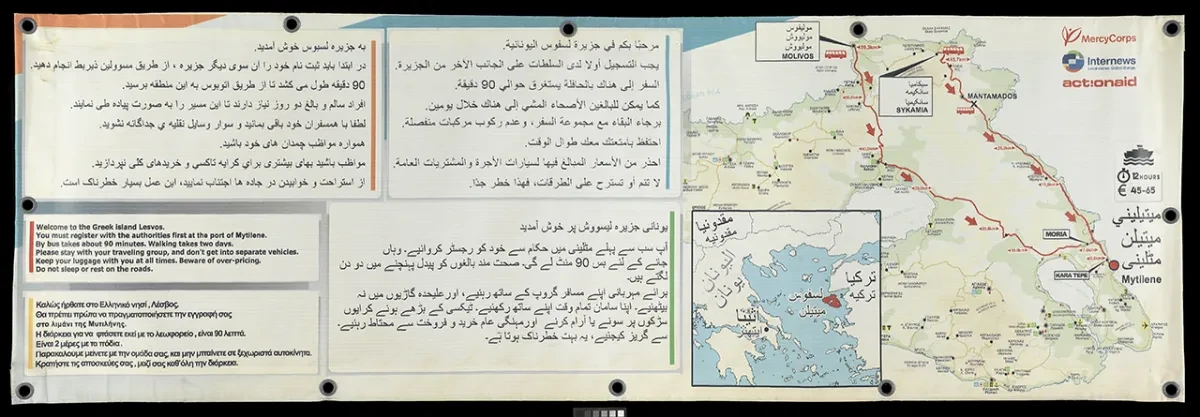

Lesvos and the Aegean Sea, 2015

This map was made as a banner, to give local information to refugees arriving on the Greek island of Lesvos, by Internews. It was designed as one low-tech way to meet basic information needs of people when they first arrived on the island, often disoriented.

The English text reads: “Welcome to the Greek island Lesvos. You must register with the authorities first on the other side of the island. By bus takes about 90 minutes. Walking takes two days. Please stay with your travelling group, and don’t get into separate vehicles. Keep your luggage with you at all times. Beware of over-pricing. Do not sleep or rest on the roads."

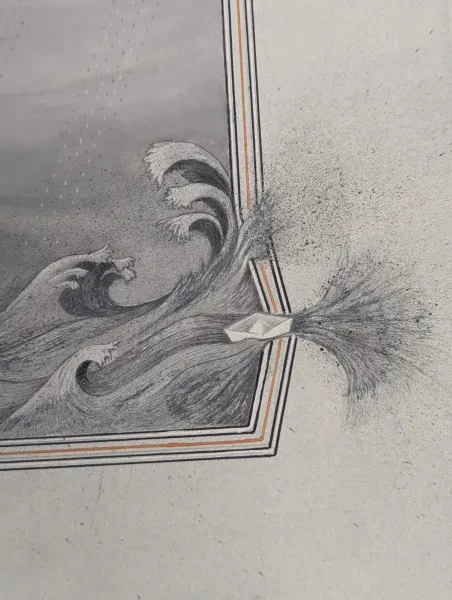

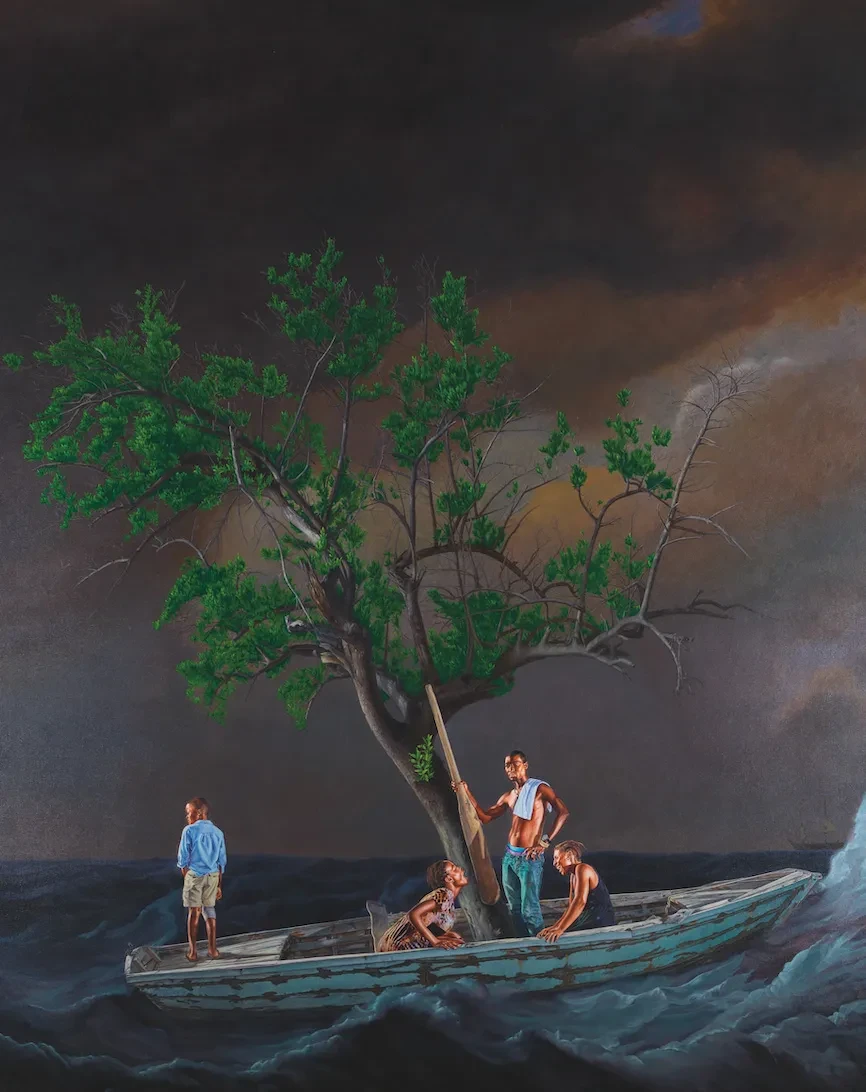

Ship of Fools by Kehinde Wiley, 2017

Kehinde Wiley’s contemporary artwork Ship of Fools re-interprets and reimagines the traditions of seascape painting.

The large-scale painting explores themes such as migration, dangerous sea crossings and the legacies of the transatlantic slave trade. The work is currently on display at the Queen's House, providing a deliberate contrast to the more traditional artworks found in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection.