This blog threads together a selection of items from the collections of the Caird Library and Archive that record the experiences of seafarers visiting the islands of St Paul and Amsterdam in the southern Indian Ocean.

The small volcanic islands of St Paul and Amsterdam are remotely situated roughly halfway between the continents of Africa and Australia. For much of their history, they remained wild and uninhabited, only a temporary home for workers in the sealing and fishing trades, or seafarers marooned there by accident.

However, as revealed in various manuscripts and rare books, there were many episodes of British ships sighting and visiting the islands.

Navigational aids

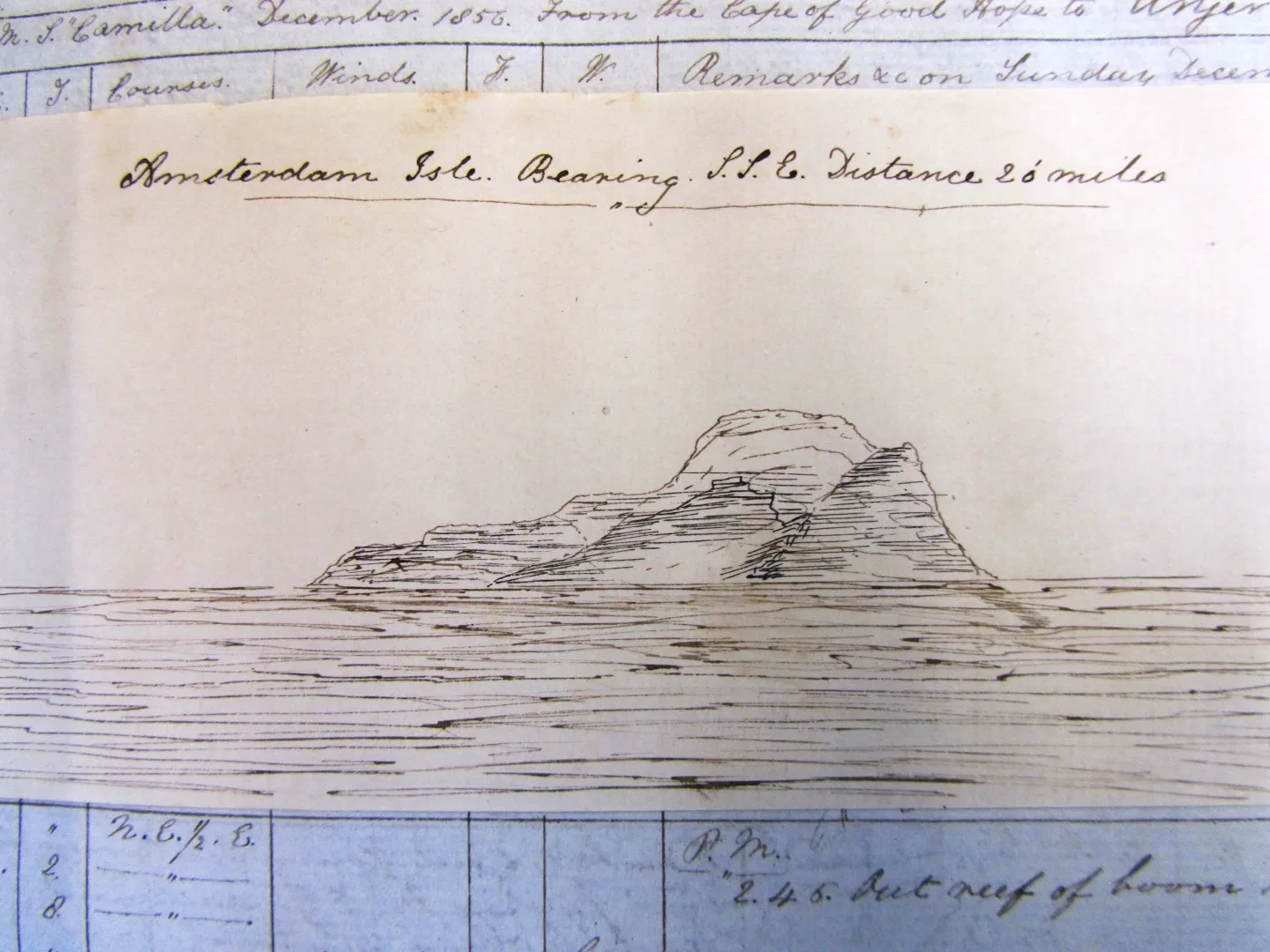

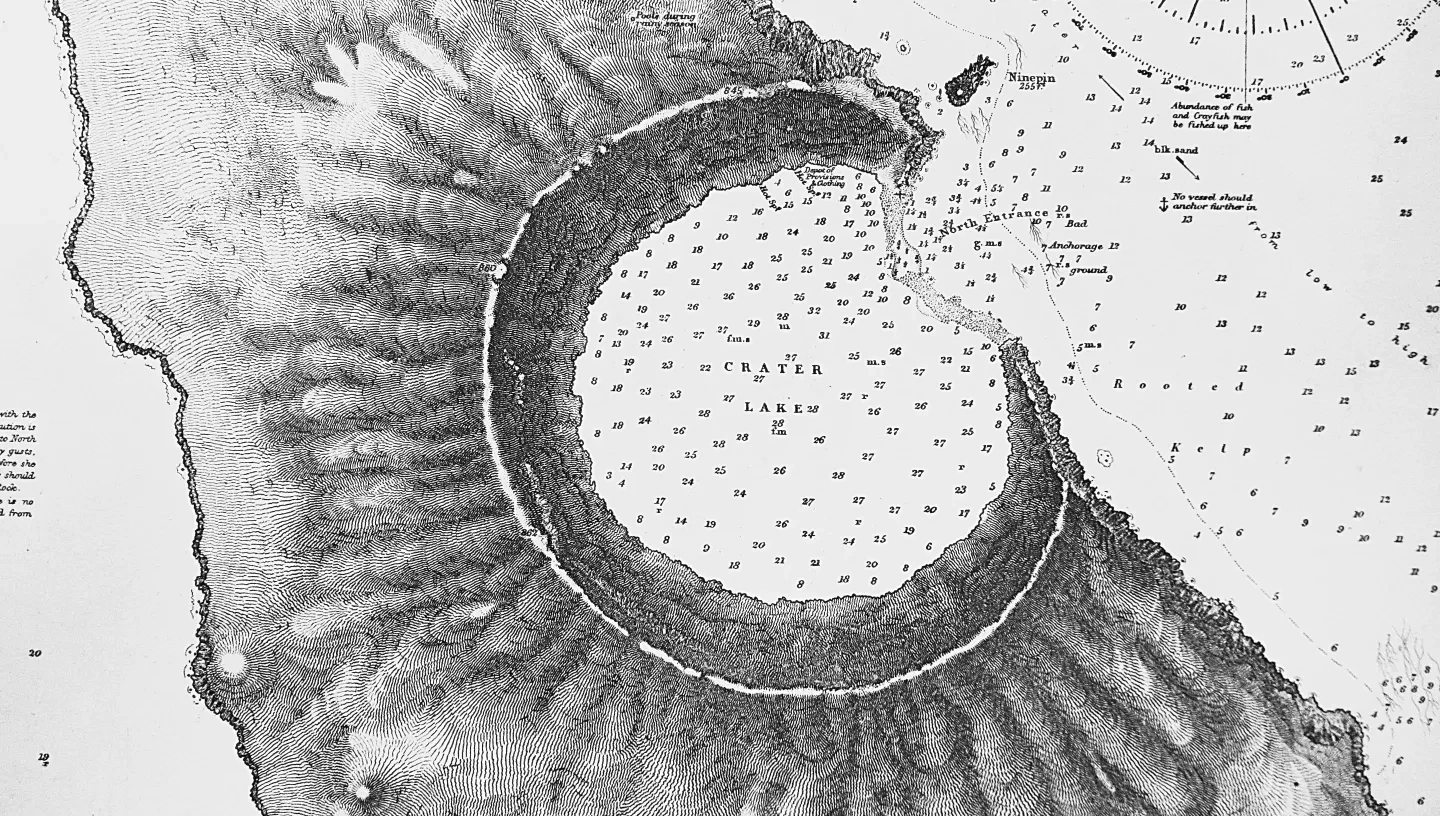

In navigation practice of the past, sailing ships rounding the Cape of Good Hope to cross the Indian Ocean took advantage of the strong westerly winds (acting eastwards) in the southern latitudes. Ships making for the southwestern coast of Australia had a long spell of running eastwards between the southern latitudes of 40 and 50 degrees (the ‘roaring forties’). Those bound for the East Indies typically kept to a southern latitude of around 37 degrees until they sighted one of the islands of St Paul and Amsterdam. It was then time to set a north easterly course for finding the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java.

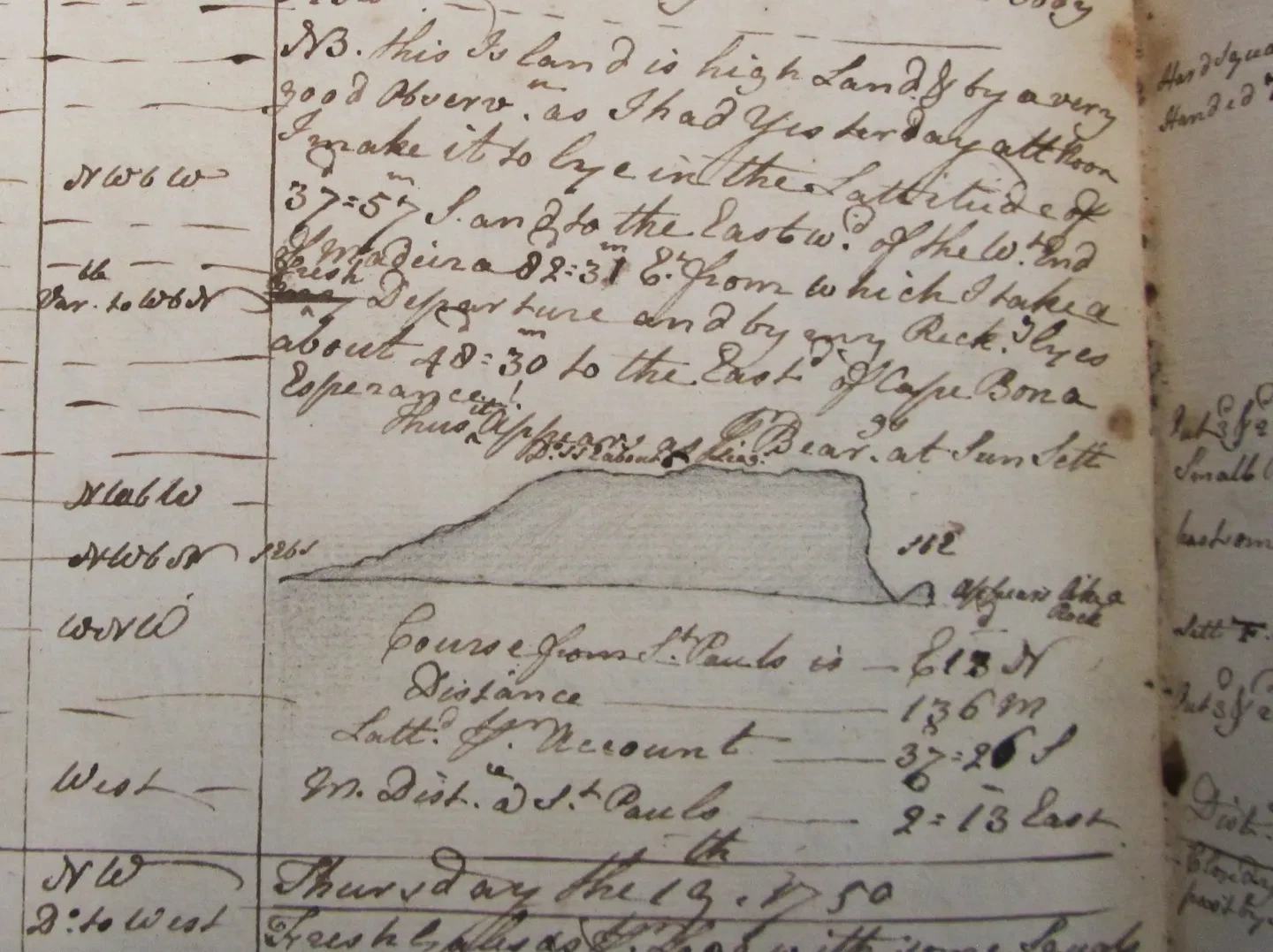

The role St Paul and Amsterdam had as navigational markers is conveyed in the log kept by William Abdy, sixth mate on the East Indiaman True Briton (1746) during a voyage to China in 1750 (CAL/201). The crew started to look out for the islands around three months after departing from the Downs. They would first expect to see patches of floating seaweed extending over a considerable distance. Once they had gained sight of the island of St Paul, Abdy made a profile drawing for his own reference.

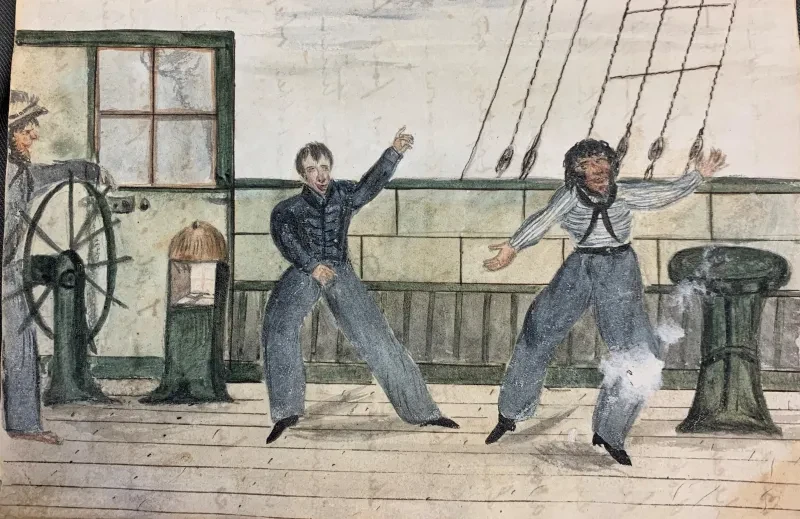

Abundant marine life

Visitors to St Paul and Amsterdam were always outnumbered by marine animals, including seals, albatross and penguins. An early narrative describing some of these creatures is the journal of Edward Barlow (JOD/4/281). Barlow was chief mate on the maiden voyage of the East Indiaman Wentworth (1699) when he encountered the island of St Paul and its large community of seals:

And coming near the island, it appeared guarded with wild beasts, or rather sea-dogs, which stood upon their hinder fins, or what served them for legs, with open mouths grinning with their long teeth, all along the shore.

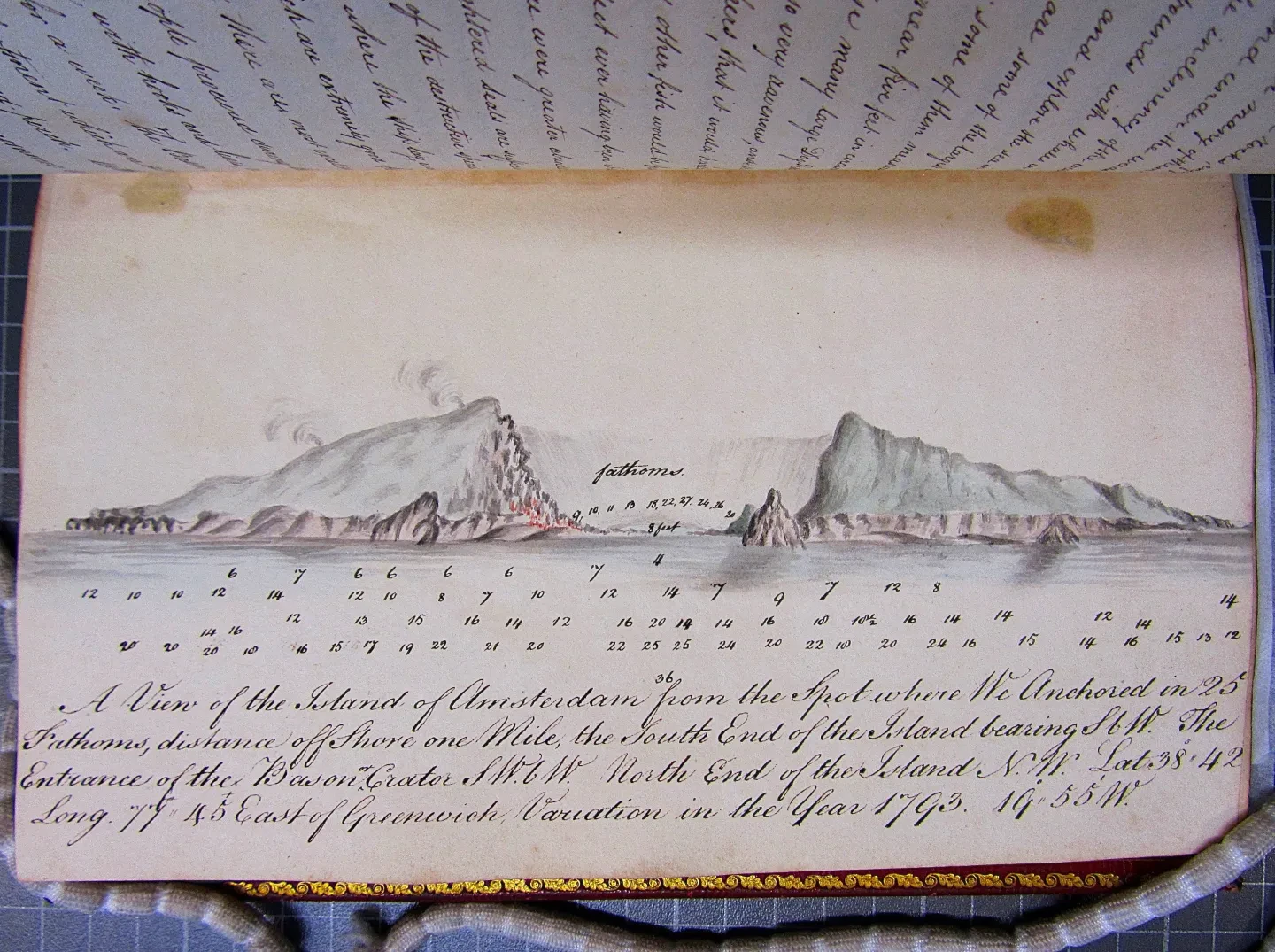

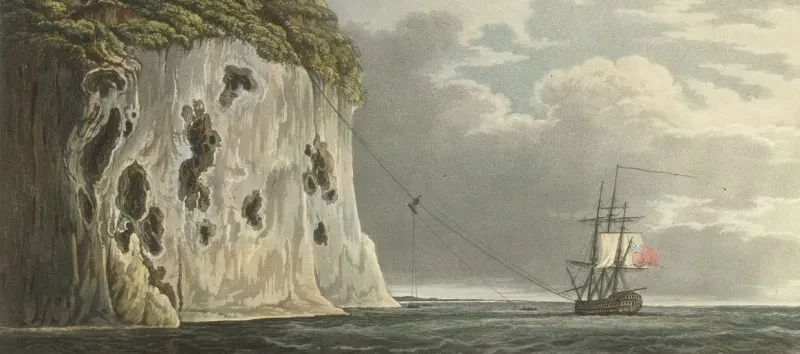

About a hundred years later, the same island was visited by the ships that carried the British diplomatic delegation to China, headed by Earl Macartney. The voyage of HMS Lion (1777) from Spithead was recorded in a log kept by Captain Sir Erasmus Gower (GOW/3). The entry he made in the log on 1 February 1793 mentions the killing of seals by a party of hunters:

As we sailed along the island, we saw smoke in several places and soon afterwards two men who made signals to us…[They] were employed by the French from the islands of France to procure seal skins. There were five of them, had been here as many months, and were to remain ten months longer. [They] had killed 8000 seals.

On the following day, the Lion safely anchored near to the basin formed by the collapsed crater of the island of St Paul. The sea here had an abundant supply of fresh fish and this brought a welcome change in diet for the ship's company.

Gower's description of the crater and its thermal springs clearly place him on the island of St Paul. However, he names the island as Amsterdam and repeats the error in his volume of nautical observations from the same voyage (GOW/1). It wasn’t uncommon for seafarers to confuse the two islands, understandable if they had spent many weeks upon the wide ocean, hoping for the pleasing sight of land.

Ordeals of shipwreck survivors

Two notable narratives relating to the island of Amsterdam concern passenger vessels that struck the surrounding rocks and went to pieces in the heavy surf during the darkness of night. Survivors from these shipwrecks endured several days of difficulties with the terrain and inadequate supplies before they could be rescued.

An account of the loss of the barque Lady Munro of Madras by John McCosh was published in Glasgow in 1835 (PBB4695). An account of the loss of the full-rigged ship Meridian (1852) written by Alfred J.P. Lutwyche is reproduced in a book by Joy Shepherd telling the story of the Scoltock family (PBP4011). The survivors from the Meridian had to climb steep cliffs and cross the island to reach a suitable landing place for a boat to take them off.

In 1871 the iron screw troopship HMS Megaera (1849) was run ashore on the island of St Paul after corrosion caused major leaks in the hull’s iron plating. The crew and passengers spent nearly three months in an encampment on the island before they were able to continue their journey on a ship chartered by the British government. These events are told in the journal of William Mason (JOD/261/1) and transcripts of letters written by Robert Horace Walpole (TRN/82).

In search of castaways

During the second half of the 19th century, the southern Indian Ocean became less frequented by seafarers. Steam-driven merchant ships usually had no reason to go so far south, particularly after the opening of the Suez Canal. However, several British naval vessels visited the islands of St Paul and Amsterdam (and the similarly remote island groups of Crozet and Kerguelen) while engaged in surveying duties or searching for evidence of missing ships.

One vessel that disappeared in the southern Indian Ocean was the iron ship Knowsley Hall (1873), which departed from London bound for New Zealand at the beginning of June 1879. Nobody spoke with or heard of this vessel in the following months and no evidence of its fate was ever found.

A search of the island of Amsterdam made by boats from the iron screw frigate HMS Raleigh (1873) is recorded in the journal of Robert Arthur Simpson (MSS/77/121) and letters by Thomas Murray Parks (PKS/154). Simpson’s entry for 27 May 1880 mentions the firing of guns to make any castaways present on the island aware of the ship’s arrival. They only succeeded in upsetting a herd of feral cattle, still in residence almost a decade after an unsuccessful attempt to create a farming settlement:

After spending some time looking for an anchorage and finding none and after hoisting the ensign and firing guns we stood on under steam to steam around the island, continuing to fire guns occasionally. We got a splendid view of the shore in clear fine sunny weather for some time and among other things, noticed a herd of five fine bullocks or cows, probably quite wild, who were startled by our guns.

As part of the operations on remote islands, depots of clothing and provisions were set up for the use of castaways who might survive the future wrecking of passenger ships employed in the New Zealand and Australia trades.

Unique scientific sites

During the 20th century, France took formal possession of the two islands. Île Saint-Paul and Île Amsterdam now form part of an overseas territory known as the French Southern and Antarctic Lands. Recent narratives about the islands focus on the important research carried out by a seasonal staff of scientists, not the exploits and misadventures of seafarers.

The remoteness and relative ‘clean’ environment of the islands make them suitable sites for monitoring the effects of human activity on planet Earth, including atmospheric pollution. In addition, they are important breeding grounds for rare bird species and sanctuaries for biodiversity.

Further reading

Barlow’s Journal… by Basil Lubbock, Hurst & Blackett Ltd., London, 1934.

The page of Barlow’s journal covering a visit to the island of St Paul during his third China voyage, 1699-1701, is transcribed in Vol. II, pp.510-511 (RMG ID: PBD1653/2).

Narrative of the Wreck of the Lady Munro on the Desolate Island of Amsterdam October 1833 by John McCosh, printed by W. Bennet, Glasgow, 1835 (RMG ID: PBB4695).

The Story of the Scoltock Family and their Journey to Port Phillip Settlement in the Colony, 1853… by Joy Shepherd, published by the author, Barrack Heights, New South Wales, 1991 (RMG ID: PBP4011).

A Narrative of the Wreck of the Meridian by Alfred Lutwyche, Sydney, 1854.

A reproduction is included in the above book by Shepherd and it can also be accessed online via the catalogue of the National Library of Australia.

The Voyage of HMS Herald to Australia and the South-west Pacific 1852-1861… by Andrew David, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 1995 (RMG ID: PBP4269).

Observations on the island of St Paul during the visit of HMS Herald in 1853, together with an account of the loss of the Meridian on the island of Amsterdam in the same year, published in The Nautical Magazine, Volume 23, 1854, pp.68-81 and 260-265.

More information on the scientific work undertaken on Île Saint-Paul and Île Amsterdam can be found on the website of the French Polar Institute.