On the night of 12 November 2019, Venice was hit by a tide of water over 1.8m high.

At its peak, more than 80 per cent of the city was underwater.

Historic buildings and monuments were flooded. Businesses and homes were gutted. It was the second worst flood ever recorded in Venice.

Built in the middle of a shallow lagoon, with the winds of the Sirocco blowing across the Adriatic, Venice has always been at risk of ‘Acqua Alta’, or high water.

However, storm surges like the one that hit the city in November 2019 have become uncomfortably frequent in recent decades.

Hasn't Venice always flooded?

Flooding in Venice is nothing new. Research by Silvia Enzie and Dario Camuffo has uncovered documentary evidence of floods dating back to at least the eighth century.

The Venetian lagoon is over 500km2 in total, but has an average depth of just one metre. High tides and storms can have a severe impact on this kind of wetland environment.

Then there is the city itself, built on wooden pillars driven deep into the lagoon mud. The lowest part of St Mark’s Square is just 55cm above the current average sea level.

“When you are this close to the upper limit of the tidal range, any meteorological event can be hazardous and cause an extreme flood,” says Piero Lionello, lead author of a report into the impacts of flooding on Venice for Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. “Small increases can have a large impact.”

Is Venice flooding getting worse?

According to official city records, there have been 324 very intense high water events since 1872. More than half (187) have happened in the past 30 years.

“For many years Venetians experienced the flooding as simply a nuisance,” says Shaul Bassi, professor of English literature at Ca' Foscari University of Venice. “For kids it was a sort of entertainment — wearing your Wellington boots, wading through the water. Then of course, things became more serious.

“Now I think we need to fully understand that flooding is not just at a local level,” he explains. “Venice is at the forefront of the battle against climate change.”

What causes flooding in Venice?

Venice is already at risk during high spring tides due to its position in a shallow coastal lagoon. Seasonal sirocco winds can also cause ‘storm surges’, driving water across the Adriatic Sea into the lagoon and towards the city. When high tides and storm surges combine, the flooding impacts can be severe.

When considering why flooding in Venice may be getting more extreme, it’s important to remember both that sea levels are rising and that Venice is sinking.

The city’s ground level is currently sinking by around 1mm a year due to natural processes. Human activities have in the past made this worse, particularly the practice of pumping groundwater from beneath the lagoon in the 20th century. This activity is now banned.

As Venice sinks, it becomes more exposed to tides and storms from the Adriatic. This, combined with sea level rise, has made flooding more frequent and more severe.

Venice’s average sea level is around 32cm higher now than it was when official records began in 1872. Climate expert Dario Camuffo has attempted to trace this even further back in time, drawing on details such as the city’s architecture and algae marks in the paintings of Canaletto to find ‘proxies’ for sea level. He concludes that the average sea level has risen by around 61cm since the 1750s.

Predictions for future rises vary, but scientists are in agreement that sea level rise is accelerating due to climate change. A 2021 report published in Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences suggested that the average sea level could be anywhere from 17cm to 120cm higher in Venice by 2100.

“These are the effects of climate change,” Venice’s Mayor Luigi Brugnaro said in response to the 2019 floods. “The costs will be high.”

How much does flooding in Venice cost?

More than 80 per cent of the city was underwater at the peak of the flooding on 12 November 2019.

Following further flooding later in the year, Mayor Brugnaro claimed that the total cost amounted to more than €1 billion, from damage to buildings and businesses to lost income from tourist cancellations.

The higher water levels are also having a long term impact on Venice’s buildings and heritage.

“Many buildings in Venice were built with waterproof basements made of white Istria stone. The upper levels however were made of bricks and mortar,” explains Dario Camuffo.

“Now the waterproof level is no longer high enough to withstand the high water level. The bricks are impregnated with salt from the sea water. When the air is humid, the salt draws in water. When the walls dry, the salt crystallises. This constant cycle is destroying the bricks and mortar of Venice.”

How can Venice protect against flooding?

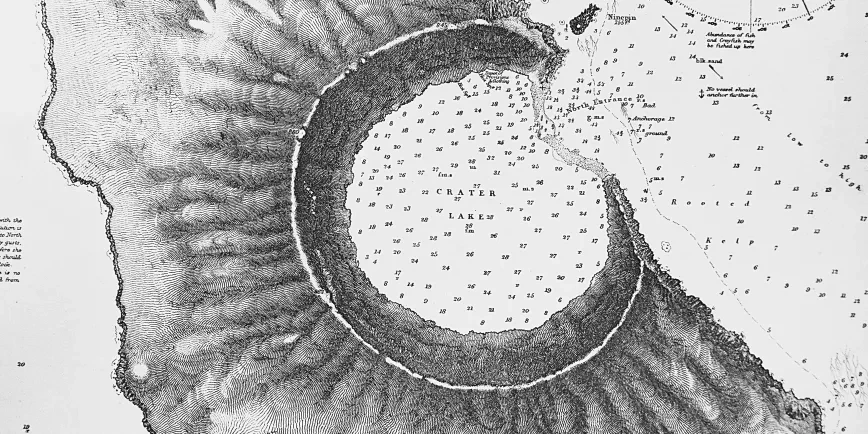

The dam system MOSE – short for Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, or Experimental Electromechanical Model – is Venice’s answer to extreme flooding.

A series of retractable barriers have been placed along the entrances to the Venetian lagoon. When high tides and storm surges are forecast, the barriers can be closed, temporarily sealing off the lagoon from the Adriatic Sea.

The project has been in the works since 1984, but has been blighted by delays and corruption scandals.

MOSE was deployed for the first time on 3 October 2020, shielding the city from a forecast high tide 135cm above normal limits. It was successful.

On 8 December 2020 however forecasters underestimated the tide level and left the barriers down, exposing the city to yet another storm surge.

The system is controversial. By closing off the inlets, even temporarily, there is concern that MOSE could cause long term harm to the lagoon habitat. There is also potential for disputes between port authorities wishing to keep the barriers open as much as possible to shipping, and residents and businesses in Venice hoping for a more conservative approach in order to safeguard the city.

Finally there is anxiety that, with sea level rise accelerating due to climate change, even this 21st century engineering solution will be unable to keep up with the pace of change.

What does the future hold for Venice?

“Sea level is rising almost everywhere on Earth. Not only is sea level rising, it’s happening faster and faster,” climate scientist and IPCC lead author Michael Oppenheimer said in 2020. Venice, he suggested, was the “canary in the coalmine” when it comes to climate change and coastal flooding.

“The rest of the world should take the message that this is what the situation is going to look like in places that they live in,” he said.

According to Shaul Bassi, this places Venice in a unique position.

“The grim scenario is that Venice will be one of the first cities in the world to succumb to the implacable rising of sea level, and will become a new Atlantis,” he says.

“Then there is the best-case scenario, which is that Venice becomes a sort of a world laboratory to think about climate change and the solutions to climate change," Bassi continues. "Not only technical solutions, but political and economic solutions, artistic solutions.

“Venice has always cherished the balance between the human and the ecological in its lagoon. It could still provide lessons, not only for itself but for all coastal cities in the world.”

For centuries, Venice has thrived thanks to its unique position in the heart of the lagoon. But if you look at the sun-drenched views of Canaletto and imagine an unchanging city, think again.

“Venice was born on water and survived on water,” says Dario Camuffo. “Water meant protection for Venetians against invaders. Instead of streets they built canals, and so from their city to the sea they could reach every part of the world. Their lives were built on water.

“Venice cannot live without water. Now it is being killed by water.”

Editor's note: This article was first published in 2022 to coincide with Canaletto’s Venice Revisited, an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum that considered the apparently timeless views of the artist Canaletto in the light of the challenges facing the city today.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.

Main image by Jonathan Ford on Unsplash