A long-lost portrait by the acclaimed 18th-century painter Thomas Gainsborough has been discovered in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collections.

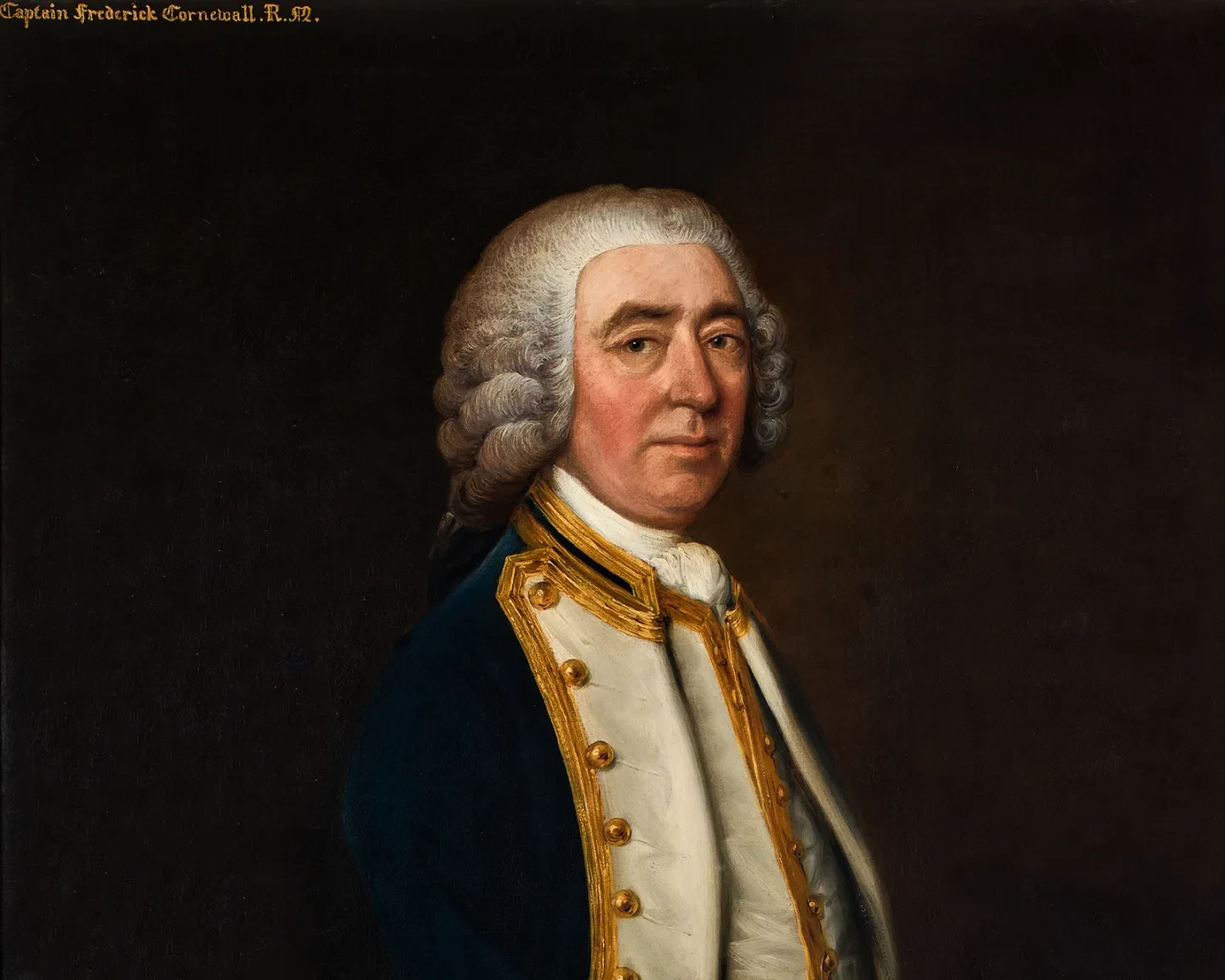

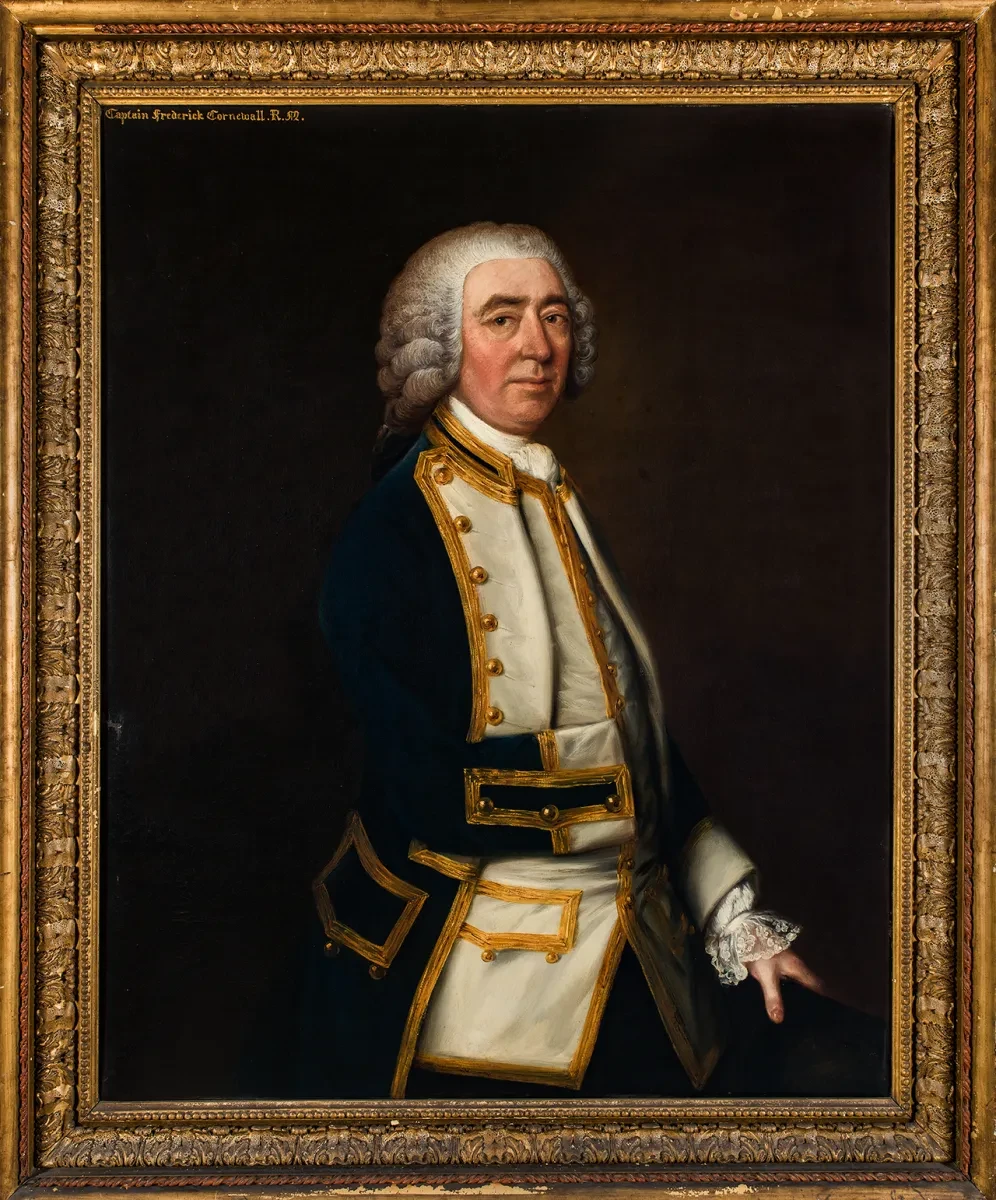

The painting, one of the finest surviving examples of Gainsborough’s early portrait work, depicts naval officer Captain Frederick Cornewall.

In 2023 the Museum launched a public appeal to conserve this historic painting. Your support helped raise a remarkable £43,000, allowing us to save this missing masterpiece from obscurity.

In March 2024 the portrait will go on public display for the first time in over three decades. It will hang in the Queen’s House alongside other important naval portraits, taking pride of place as one of the highlights of Greenwich's art collection.

Your donations are also supporting research to enhance our understanding of the portrait’s significance and engagement activities designed to share its story with visitors and local communities.

From Museum store to gallery wall, visit the Queen's House to see this rediscovered masterpiece for yourself.

How was the painting discovered?

The portrait of Captain Frederick Cornewall entered the National Maritime Museum collection in 1960. While the painting had previously been recognised as a work by Gainsborough, when it arrived at the Museum it was re-attributed to an unknown British artist.

In 2022 art historian and Thomas Gainsborough expert Hugh Belsey contacted Royal Museums Greenwich with a request. He was on the hunt for a missing portrait that Gainsborough was known to have painted, and believed the answer could lie in the Museum stores.

Belsey requested to view the portrait for himself. Upon seeing it, his instinct was confirmed: this work was not by an ‘unknown’ artist at all. It was, in fact, a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough, and one of the finest examples of his work from his Bath period.

Both the quality of the painting and its provenance leave no doubt that Gainsborough is indeed the artist.

Who was Thomas Gainsborough?

Thomas Gainsborough (1722-88) was a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, and is considered one of the most important British artists of the 18th century.

His popularity soared during the mid-1700s, and his studio was thronged with fashionable sitters, including Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and the actor David Garrick. His spirited brushwork, unique for the time, helped bring his subjects to life.

The rediscovery of this Gainsborough portrait – one of only two artworks by Gainsborough in Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection – has great historical significance, and we are keen to preserve it for future generations.

An important example of 18th century naval portraiture, the artwork provides an opportunity to compare how he and his rival, Joshua Reynolds, approached the task of portraying naval officers.

Who's in the painting?

Captain Frederick Cornewall was a naval commander, who had recently retired from active service when he sat for this portrait.

“It was made in 1762, when Gainsborough was working in the fashionable spa town of Bath,” explains Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich.

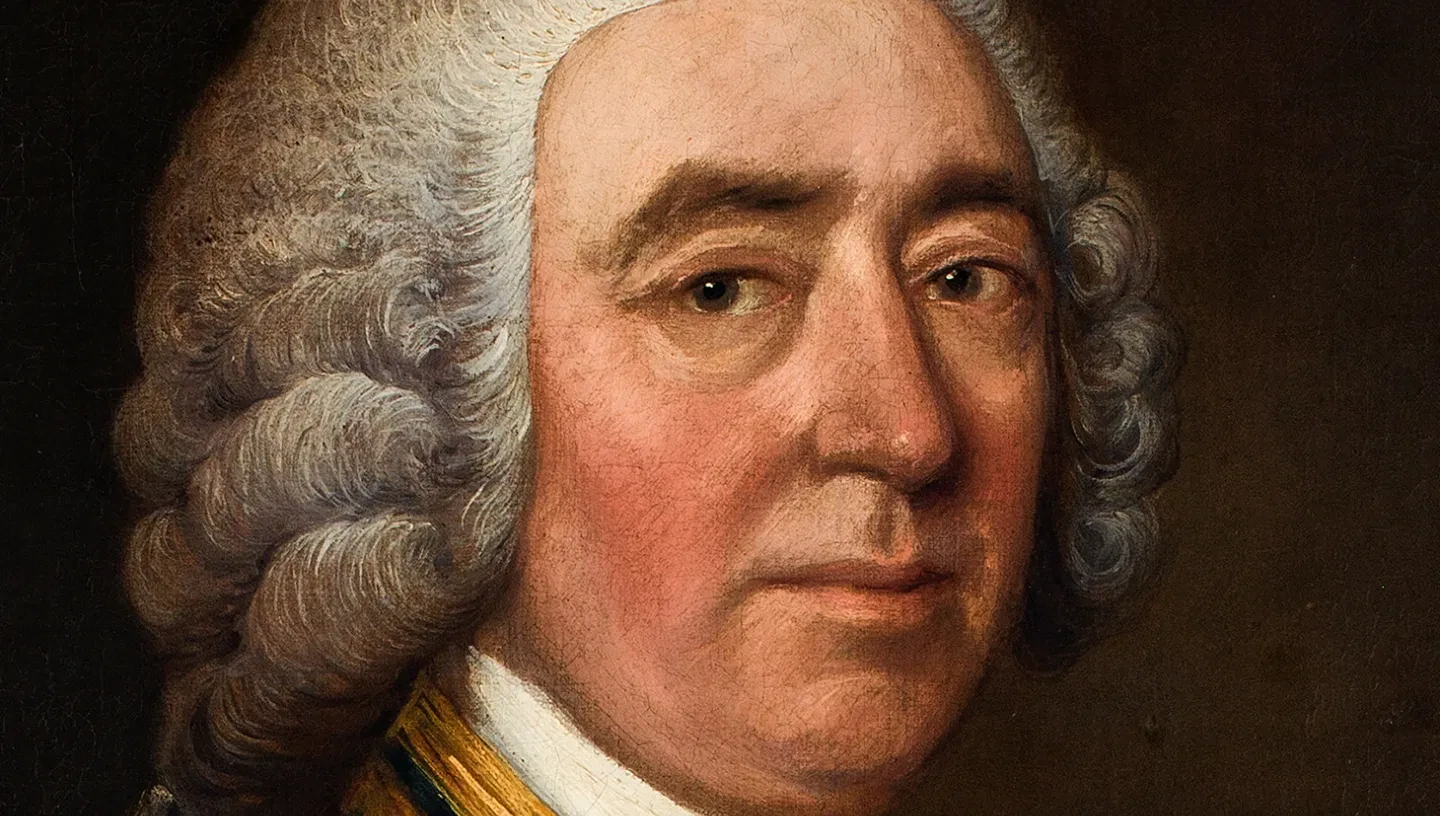

“His style was evolving rapidly at this time. In this portrait, you can see how he used rapid, flickering brushstrokes to enliven his subjects, particularly evident in Cornewall’s careworn face and his delicate lace cuff.”

One of the most interesting elements of the painting is Gainsborough’s central placement of Cornewall’s empty sleeve – a reference to the loss of his right arm at the Battle of Toulon in 1744. This depiction of Cornewall’s missing limb was painted some 40 years before Lord Nelson was depicted in the same way.

How was the painting conserved?

The portrait had been housed in the Prince Philip Maritime Collections Centre, Royal Museums Greenwich's state-of-the-art conservation and storage facility.

Before the work could go on public display however, both the portrait and its frame required urgent conservation.

Conservators identified that the background of the painting had areas of vulnerable and flaking paint, which needed to be stabilised. They also needed to clean both the front and the back of the portrait in order to remove an acidic layer of dust and surface dirt.

"There is also a varnish layer present on the painting, which as it has aged has degraded and become yellow," explains Miranda Brain, Paintings Conservation Manager at Royal Museums Greenwich. "Although it was typical of artists to apply varnishes to their paintings during this period, this is not the original varnish. This has the effect of distorting the tonal qualities and disguising Gainsborough’s true intention for the work."

The paint layers have now been stabilised, and the dust, surface dirt and discoloured varnish removed.

Following the removal of the dirt and varnish, details showing Gainsborough’s approach to painting could be better seen. It revealed the use of spontaneous brushwork in areas such as the waistcoat, emphasising the confidence and skill of Gainsborough’s paint application.

It also better highlighted the use of the ground layers as a mid-tone. The use of a warm brown ground layer was unusual in 18th century portraiture, with white-grey colours more typically seen. Gainsborough, however, uses this to full affect in this portrait, with the mid-tones in Cornewall's face comprised solely of the ground layer with no additional paint on top.

The portrait's frame was also treated as part of the conservation process. The decorative surface has been consolidated to secure any flaking and prevent further losses to the gilding.

There was previously a thick glue layer on top of the frame's gilding, which was slowly contracting, cracking and pulling off the gilding. This was leaving an alligator skin effect across some areas of the surface as well as bright patches in others. This glue has now been removed.

Losses to the surface have been filled and a previous loss to the pine carving replaced and fitted. Conservators gild these new fills and areas of damage, before toning the bright gilding so that it matches the age of the painting.

A build-up to the back of the frame has also been added, making it deep enough to fit both the painting, its new museum glass and a backboard to protect the back of the canvas.