16 July 2023 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Sir Joshua Reynolds, one of the most celebrated artists of the 18th century.

Reynolds made his name painting dramatic society portraits, and is best remembered as the first President of the Royal Academy. There are 15 paintings by Reynolds in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection.

Reynolds's contemporary Thomas Gainsborough was also a talented and successful portrait painter, but he and Reynolds approached their art in very different ways. Gainsborough’s portrait of Captain Frederick Cornewall was recently discovered in the collection.

Katherine Gazzard, Royal Museums Greenwich’s Curator of Art (Post-1800), takes a closer look at the rivalry between these two great British artists.

Who was Joshua Reynolds?

Joshua Reynolds was born in Plympton, a small town near Plymouth, in 1723. He moved to London at the age of 19 to train as an artist with portrait painter Thomas Hudson.

When his apprenticeship ended, he returned to his hometown, establishing a portraiture studio close to Plymouth’s naval dockyard in the mid-1740s. Many of his clients were naval officers, though he also painted other members of local society.

In May 1749, Reynolds travelled to Italy with Commodore Augustus Keppel, a rising star in the Royal Navy who granted the young artist passage on board his warship. This was the opportunity of a lifetime for Reynolds. It enabled him to improve his art through first-hand study of Renaissance masterpieces and ancient sculpture. The voyage also marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship with Keppel.

After returning from his travels in autumn 1752, Reynolds established a studio in London and quickly became one of the city’s leading portrait painters. He continued to work in London for the rest of his life.

Reynolds was a founding member of the Royal Academy, which was established in 1768 to provide a space for artistic debate and education. His fellow Academicians selected him as their first President. He held this role until his death in 1792, delivering annual lectures on art theory and becoming one of the most influential voices in British art.

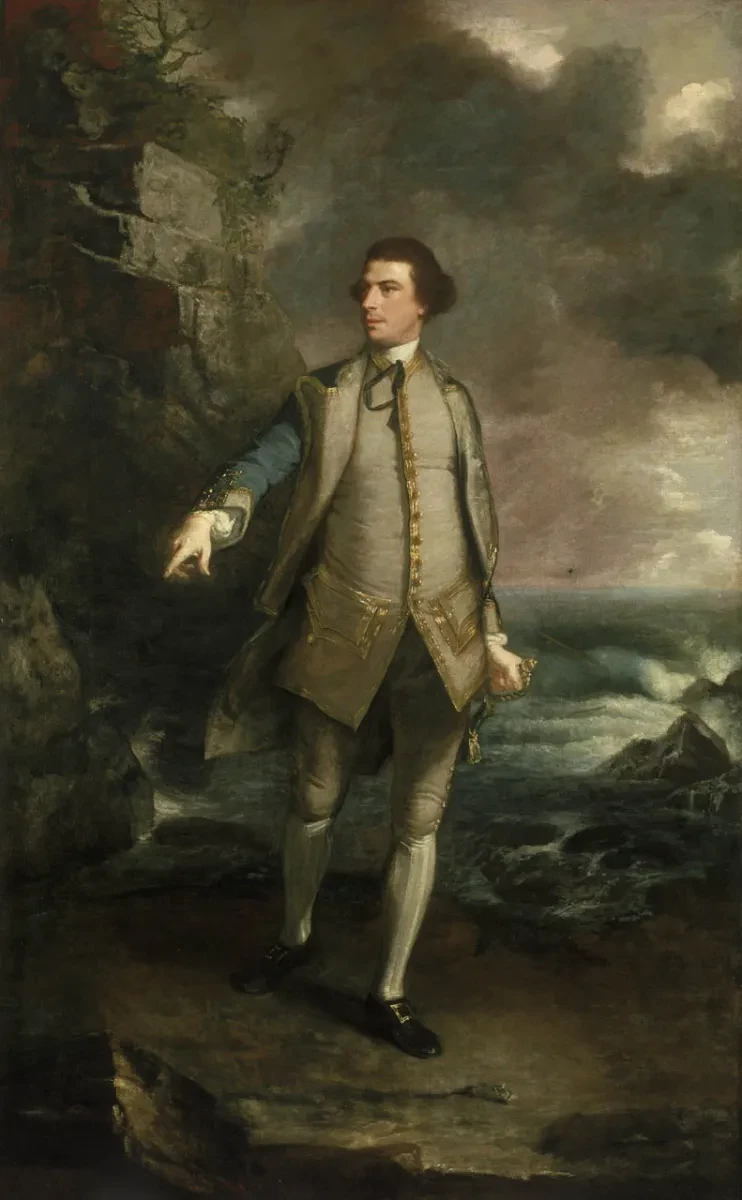

Reynolds’s artistic ambitions are expressed in this portrait of his friend Augustus Keppel that he painted after returning from Italy and establishing his London studio in 1752.

This portrait demonstrates Reynolds’s admiration for ancient sculpture and Renaissance painting, both of which he had studied during his travels. Keppel’s striding pose is derived from a classical statue, while the painting’s dramatic use of light and shade echoes the work of 16th-century Venetian artists like Tintoretto.

The painting also showcases Reynolds’s interest in depicting moments of significant action. Keppel is shown taking command in the aftermath of a shipwreck. Thin strokes of brown paint in the storm-churned waves represent the shattered planks of his lost vessel.

For many years, Reynolds displayed this portrait in his studio to show potential clients what he could achieve. It played a key role in establishing his reputation and is one of his most important paintings.

Who was Thomas Gainsborough?

Gainsborough was four years younger than Reynolds. He was baptised in the Suffolk town of Sudbury on 14 May 1727. Like Reynolds, he came to London in the early 1740s to seek artistic instruction, which he received from the French engraver Hubert-François Gravelot.

After studying with Gravelot, Gainsborough went back to Suffolk to paint portraits of the local gentry. This mirrors Reynolds’s return home to Plymouth following his own apprenticeship in London. However, whereas Reynolds went on to visit Italy, Gainsborough never left England.

While Reynolds was growing his popularity in London in the 1750s, Gainsborough moved to the West Country. He established a profitable studio in the fashionable spa town of Bath, where he painted portraits of wealthy individuals who came to take the waters.

From Bath, Gainsborough sent paintings to be exhibited in London, where they vied with Reynolds’s pictures for public attention. Then, in 1774, he moved to the capital, bringing himself into direct competition with Reynolds.

Like Reynolds, Gainsborough was invited to become a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768. However, his relationship with the Academy was distant and conflicted. He boycotted the Academy’s annual exhibitions between 1773 and 1776 and again from 1784 until his death in 1788, complaining about how his paintings had been displayed.

Gainsborough’s mastery of subtlety is displayed in this portrait of naval officer Frederick Cornewall. This portrait was made in Bath in 1762 and may commemorate Cornewall’s retirement from active naval service the previous year.

The painting is not dynamic, like Reynolds’s portrait of Augustus Keppel. It has a quiet dignity appropriate for a retirement portrait. Cornewall stands in his wig and naval uniform in front of a plain background.

Gainsborough brings this simple composition to life with scintillating brushwork. Cornewall’s features appear careworn, and his lace cuff looks delicate.

A key feature of the portrait is the empty right sleeve of Cornewall’s coat. The captain had lost his arm at the Battle of Toulon in 1744. Men in the 18th century were often painted tucking one hand into their waistcoats to symbolise self-restraint and modesty. Gainsborough mirrors this familiar pose in his depiction of Cornewall’s missing limb, presenting the captain’s disability as proof of his fortitude, humility and dedication to duty.

This portrait was recently rediscovered, having been miscatalogued as the work of an unknown artist since 1960.

What was their rivalry about?

As portraitists, Reynolds and Gainsborough competed with one another for commissions, but their rivalry went deeper. They held fundamentally different ideas about art.

Reynolds believed in taking inspiration from earlier art, particularly the classical forms of Greek and Roman statuary. He also thought that artists should capture grand moments from history and imbue their paintings with intellectual and moral complexity.

By contrast, Gainsborough aspired to record the fleeting light effects and sensory impressions of everyday life. He wanted to delight the eyes and appeal to the emotions, not stimulate the mind.

Gainsborough once described his style of painting as 'a flash in the pan'. This self-deprecating statement implies that his portraits are all style and no substance, but this is not true. While his paintings emphasise texture, colour, pattern and other decorative details, they also offer sensitive representations of character. What they lack are the classical poses and art-historical references that Reynolds favoured.

Despite their differences, Reynolds and Gainsborough held each other in high esteem. In 1788, Gainsborough was dying from cancer and sought reconciliation with Reynolds. He wrote a letter to his rival stating that, 'I can from a sincere heart say that I always admired – and sincerely loved – Sir Joshua Reynolds.'

After receiving this letter, Reynolds visited Gainsborough in his studio. He later said of this meeting that 'if any little jealousies had subsisted between us, they were forgotten'.

Explore the collection

Find more artworks by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough at Royal Museums Greenwich