By Steph Morris | Published 14 Jan 2026

It began with a love of singing shanties, but also with queries – could the lyrics be queered? They could and should.

Sea shanties have always been chopped and changed, communal property passed back and forth and adapted to suit.

In other choirs I’d sung shanties and songs of the sea, but I was often bothered by lyrics which seemed colonialist, sexist or normative, while others were already quite queer and just needed resonance.

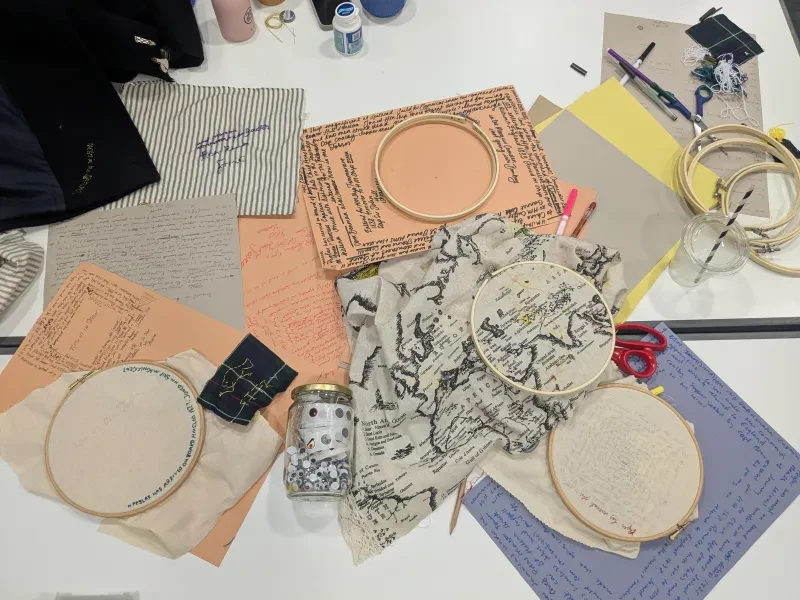

Could we rise to the creative challenge and add new words of our own as a group?

Queer History Club Choir

Queer History Club (QHC) is a coalition of queers meeting at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich to support each other in their investigations of the collection.

We often need support because of the obstacles to queer research and the new Queer Research Guide provides the advice and inspiration we felt was needed. The QHC Choir has now become one of the club’s side quests, including QHC members and singers drawn from other local groups.

Musician Sonny Brazil has been performing and adapting folk music, including songs of the sea, for years, and led us as musical director in our queer quest. We had just three rehearsals before we were booked to sing at the Sea Shanty Festival on Cutty Sark.

About sea shanties

Actual shanties, as opposed to sea songs, were traditionally sung to aid repetitive, physical tasks, so we had already lifted them from their original context by singing them in workshops and concerts for fun.

Singing, however, is uplifting, and could help us with our own work – in this case reclaiming songs, righting wrongs and making sure queer stories are told. Shanty lyrics were often very anti-establishment, and when we came to change them, we leant into that.

Shanties were often first written down and standardised long after they were originally sung, and there are multiple versions of each, so it made sense to continue this tradition by creating new variations.

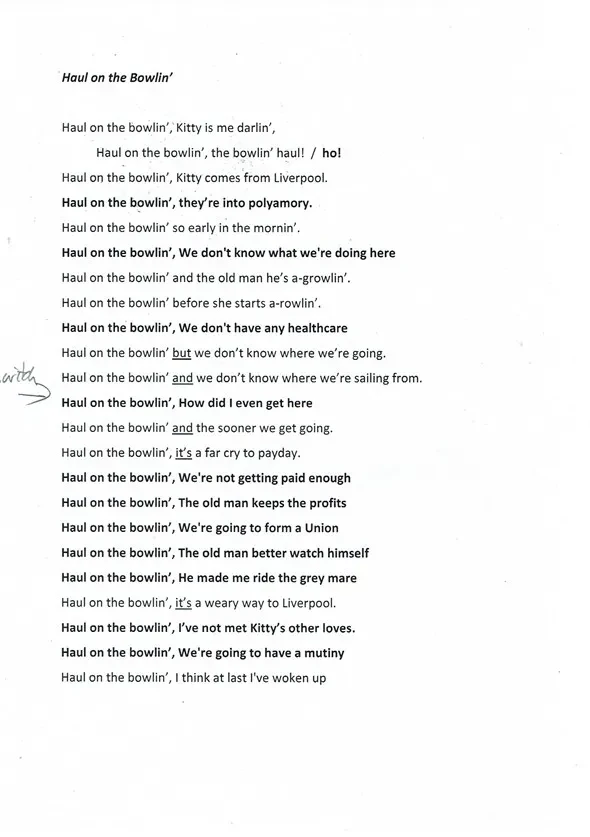

For ‘Haul on the Bowline’, we started with the words sung in the 1960s by The Young Tradition. A bowline is a rope that pulled a sail towards the bow of the ship. The song is driving, ceaseless and circular; the verses and chorus overlap with no breather so at least two singers are always needed. We divided into two groups and swapped roles half way. The song already included some hints of the sailors’ dissatisfaction with their working conditions, and general bewilderment so we took this to its logical conclusion and asked, 'Who was Kitty from Liverpool? And what relationship did the singer have with them?'

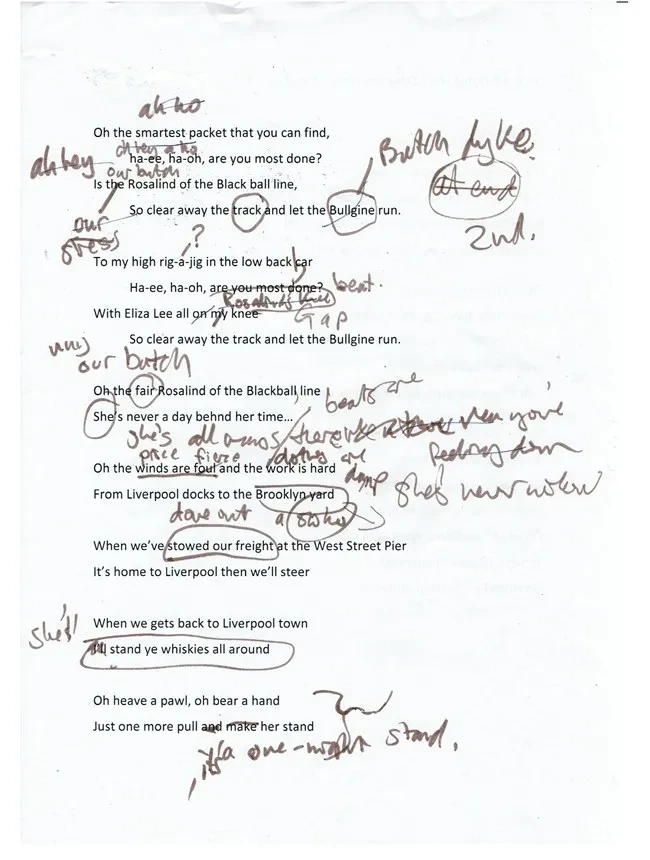

Our starting version of the song variously known as ‘Let the Bullgine Run’, ‘Clear the track’, or ‘Eliza Lee’, was already of mixed provenance: based on the version I had sung in another choir but altered to make it closer to the version Sonny knew.

Perhaps more a docks' song than a shanty (a ‘bullgine’ is a railway engine), it travelled the world, picking up global influences, and was certainly sung in port towns in the American South, where African Americans contributed to it. Now it had docked with a group of queer singers in south London. We were grateful for the material passed to us and got to work adding our own influence.

The ship Rosalind, or Margaret Evans in some versions of the song, was described as ‘fair’. After a brief discussion we made her a person instead and found the best adjective for her had to be ‘butch’. And it was Rosalind’s knee Eliza Lee was going to sit on. The rest of the song became a narrative of partying, queer solidarity, and admiration. When we landed on the refrain ‘Let the butch dyke run’ we knew we had arrived.

As we only had time for a couple of workshops before the performance, we weren’t able to change every song. Some shanties gained a new dimension simply by being sung by a queer choir; we sang the version of ‘Roll the Old Chariot’ by Danny Spooner, as found here, unaltered, keeping a straight face. It is a lot about what is between the lines anyway but we will likely be reworking this one in the future…

When we performed our songs at the Cutty Sark Sea Shanty Festival on board an actual ship, on the ‘Tween Deck and then below the bows in the Dry Dock, backed by a chorus of figureheads, the effect was sharpened, with added realness and also otherness. The raised eyebrows, out-loud-laughs, joy, astonishment and discussion we provoked put fresh wind in our sails.

More on sea shanties

The Caird Library and Archive at the National Maritime Museum has books (and LPs!) of sea shanties, including:

- Stan Hugill's Shanties from the Seven Seas (PBF1980) and other books by Hugill

- A sailor’s life: The Life and Times of John Short of Watchet 1839-1933 (PBH6958): John Short collected shanties and passed 57 on to Cecil Sharp

- Many books by sailor-poet John Masefield such as A Sailor’s Garland (PBC8086), an anthology of poems and shanties