By Ema Sala | Published 10 Feb 2026

How can historical research be an act of solidarity with working people in the past? How does gappy archival material benefit from being looked at in a queer way?

I've been a researcher at the National Maritime Museum for three years with the Queer History Club, a collective of queer researchers and artists. My latest obsession are sailors' writings – not officers, but common sailors. The Caird Library has several of these, in the form of diaries (JOD/224/2), and letters (AGC/B/26), but the celebrity in the group is definitely the one known as the Peglar Wallet (ACG/36).

Henry Peglar is a known figure because he participated in the Franklin expedition, which set off to discover the Northwest passage in 1845 and was lost sometime in 1849.

Peglar was a petty officer, which is a sort of middle management figure on a ship: he was Captain of the Foretop on HMS Terror. He was born in Westminster, where his dad John was a gun maker. He had a sister called Sarah. He was only 38 when he died, but he'd had a long career aboard ships that started when he was 14 years old. His papers were found in the 1850s during the Fox rescue expedition, one of the many rescue missions sent from England to discover the destiny of the Franklin expedition.

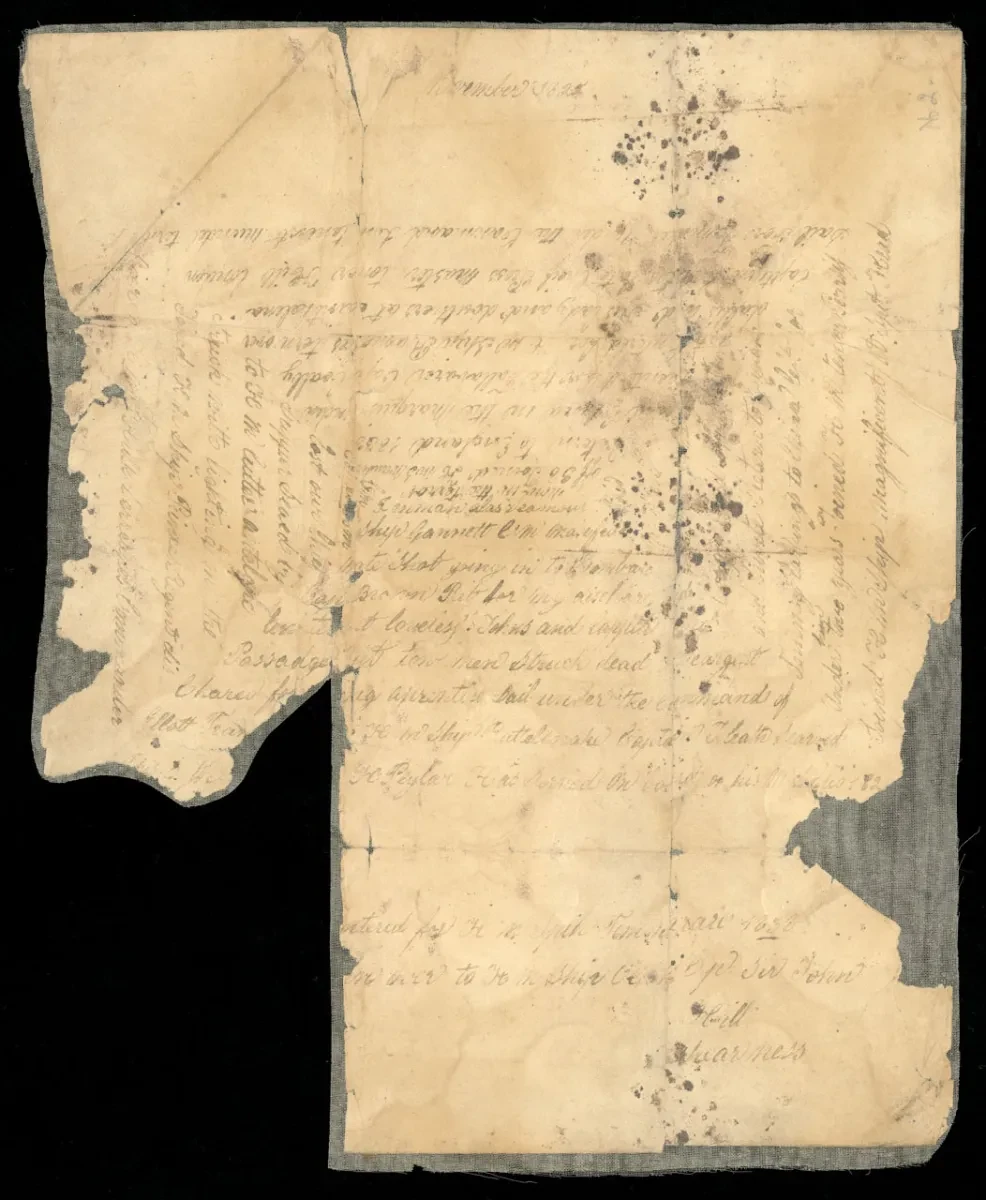

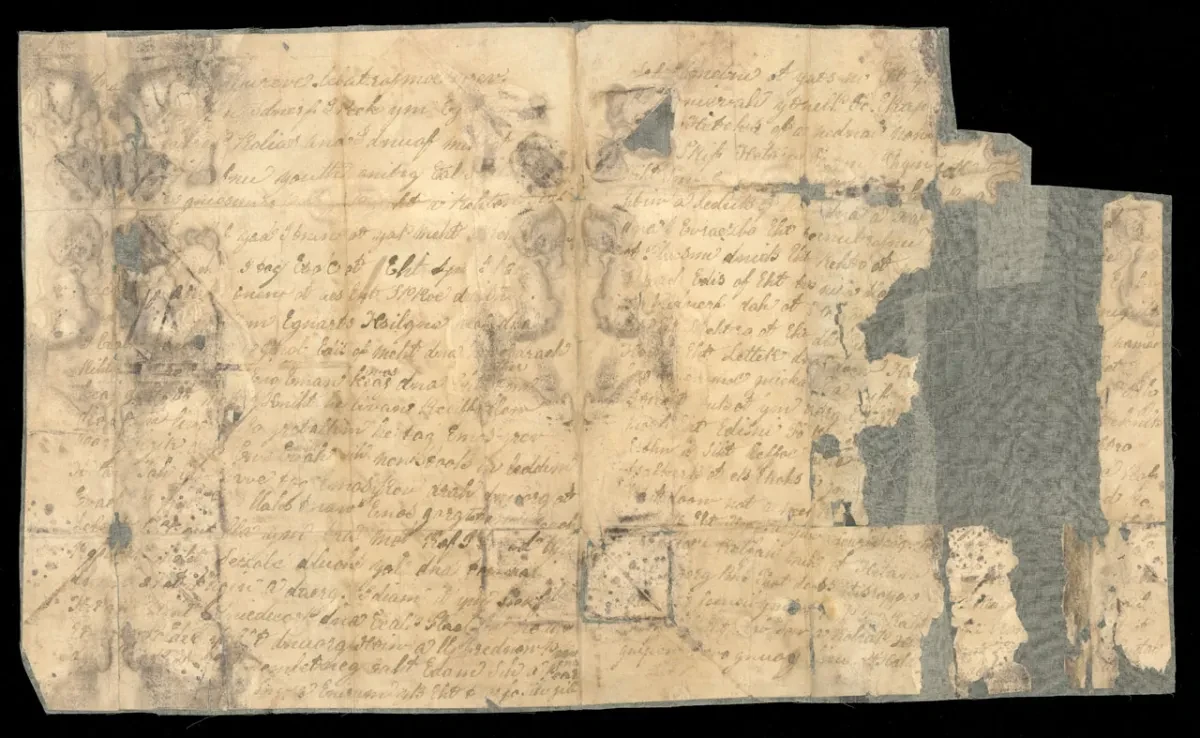

The wallet itself tells us no hard facts about the fate of the expedition. Its contents, however, say a lot about who Peglar was as a person. For instance, they contain an account of his career. He chose to write this in a square shape, or rather like a square spiral curling around itself, like a labyrinth. The list of his appointments starts on the outer edge, written economically but vividly. In the middle of the labyrinth sits the sentence: now in the Terror.

The placement is haunting, an immediate reminder that working in the Terror caused Peglar's death; that in a sense, the Terror was Peglar's tomb.

In general, Peglar was an artsy guy: the wallet also contains a poem or song, Barry Cornwall's The sea, that he reworked into a maybe-sexy parody, and a small piece of writing in the shape of a circle, perhaps also a poem.

There are, too, several pages recording his adventures which are written backwards, with every word starting with the last letter and ending with the first. These documents are very damaged, turning a narrative which must have once been clear into a halting, enigmatic one.

Together with the letters is Peglar's seaman's certificate, an official document attesting his service in the Navy. The certificate is fleshy, made of leather: it looks like mummified skin because it is. It tells us about Henry's physical appearance: his eyes were hazel, his hair was brown, and his complexion was "sallow". It's just enough to start painting a picture in your head, but one that is elusive.

Reading the existing scholarship on Peglar, I can see that their gappiness is often seen as frustrating, hampering our knowledge of the Franklin expedition's fate. I really like it, though. As a researcher in queer history, I am used to wrestling with mystery, and the Peglar papers are certainly queer: in the way that they invite oblique readings to fill in the gaps, how they hold back information in a winking, slippery way, and in how playful and fun they can get.

In addition, Peglar's disinterest for the big muscular events of history and his interest in practical and beautiful things, described effectively and poetically, deeply resonates with me.

When I saw the wallet in person for the first time in Autumn 2024, I knew I wanted to show it to more queer people, to hear what they thought and how they would fill those gaps.

I asked my Queer History Club gang if they would like to join me, and a few of us formed the Peglar Papers Reading Group. Our groupchat, by the way, is called P-P-P-Pick Up a Peglar, which we think Peglar, who was a funny guy, would enjoy.

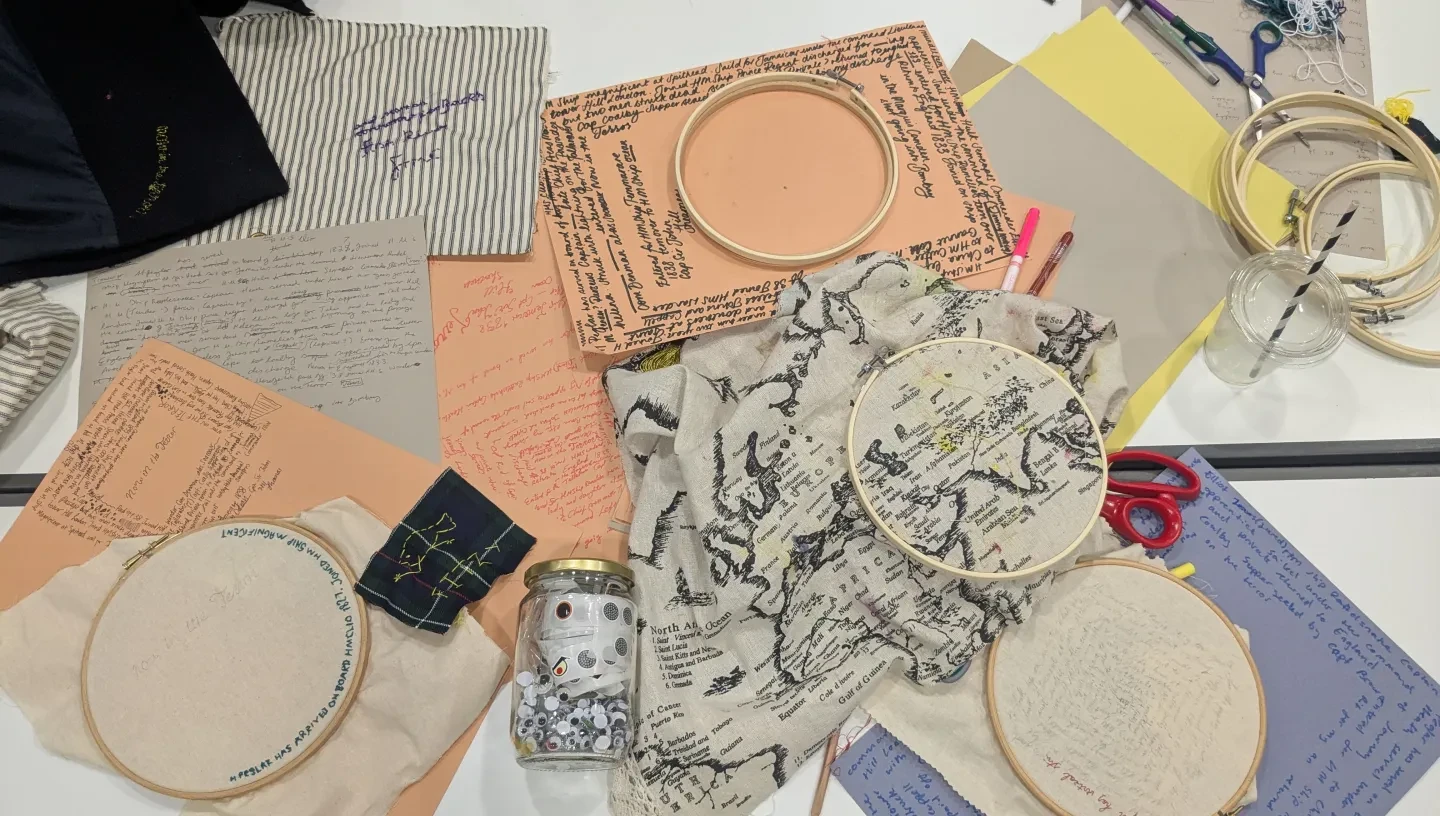

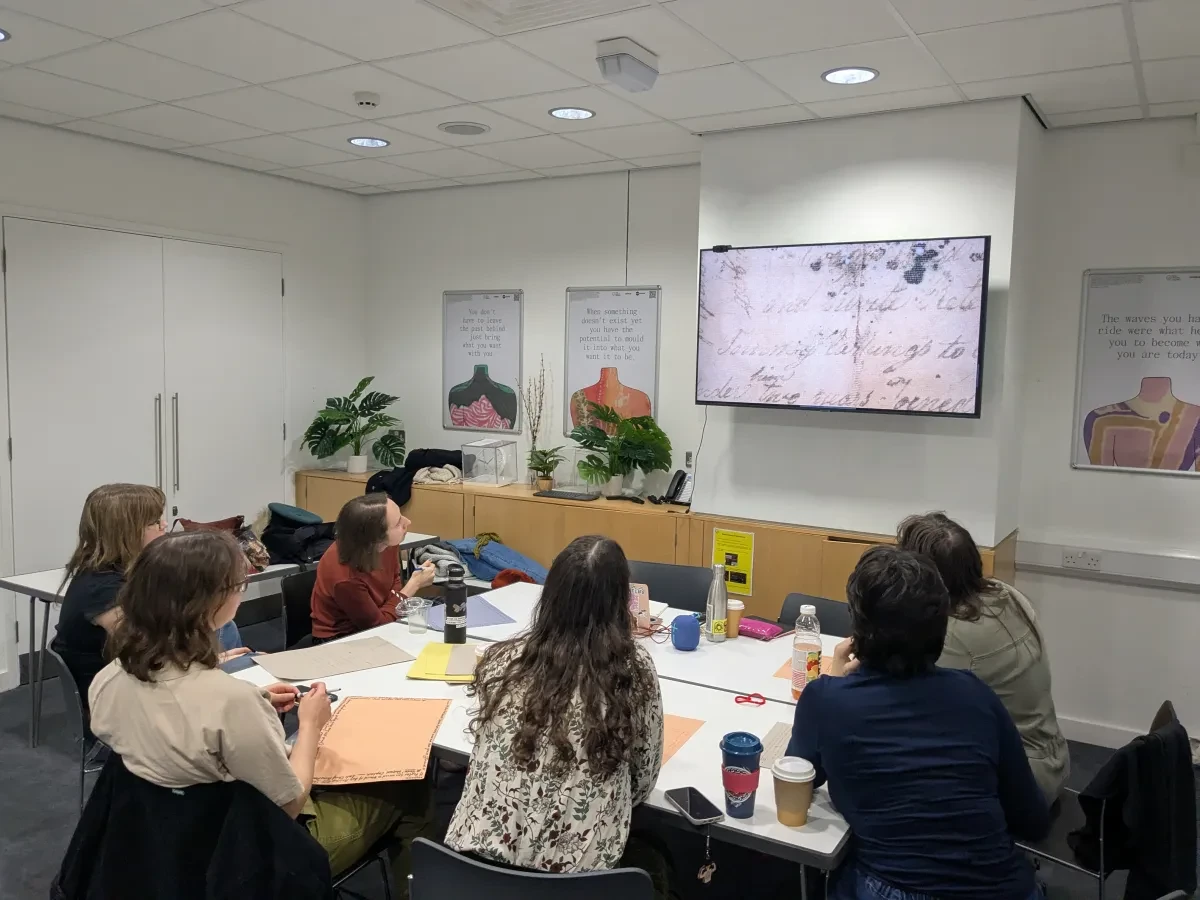

We had four meetings during March and April, working on the papers for a total of 12 hours, with four to seven participants.

Because the papers themselves are quite small and fairly fragile, the Caird Library mediated for us to get high-resolution reproductions of some of the contents of the wallet. In the meetings, we often commented on the crispness of the files, which let us feel that we were getting up close and personal to Peglar.

We regularly expressed how we felt we knew Peglar in person: we often joked about 'Zooming' him in to our meetings ask him about the bits of his writings we couldn't decipher. We did this while giggling, picking up an imaginary phone – but this was also us facing the deep stuff of historical research: a yearning for a relationship with long-dead people, the same reaching-out as a necromantic act.

Throughout, Peglar's creativity and artsiness really jumped out of the page for us. For instance, while reading his rendition of the poem The sea, we noticed that he annotated it with letters that made us think of musical notation. We imagined a Peglar who made music, like many sailors did.

Indeed, I later found the original poem in a book of broadside ballads at the British Library, evidence that it was sometimes sung. Reading the Peglar wallet with another group, we found a section of backwards writing that reads like a ballad, perhaps one he was composing.

While most of our conversations about the papers came about organically, I also prompted the group with questions and warm-up exercises, where I invited us to compare the Peglar papers to other documents reminiscent of his style: a letter written by a sailor in 1796 (AGC/B/26), Emily Dickinson's envelope poems, and a letter written by Jane Austen in reverse, as a joke, to her little niece.

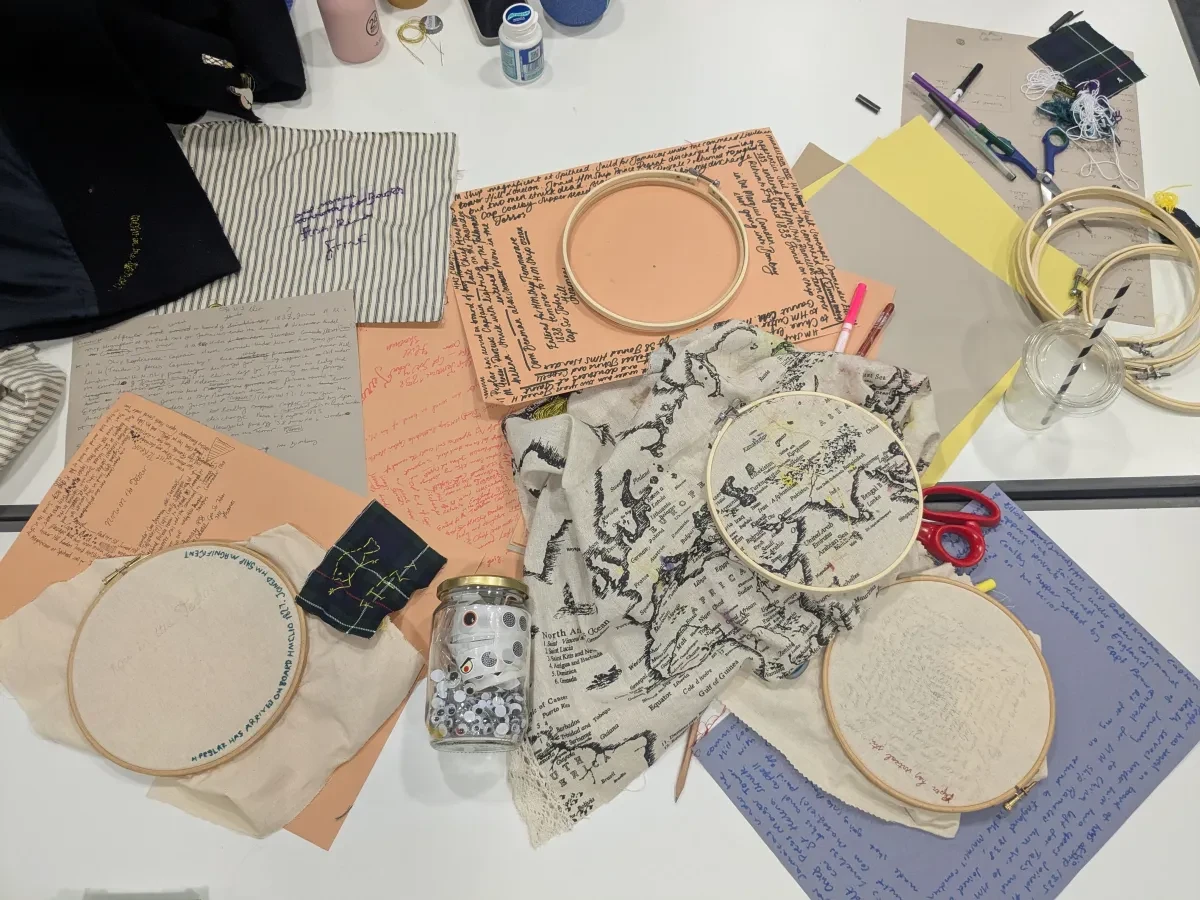

An autobiographical embroidery sampler stitched by a maid called Elizabeth Parker in 1830, now held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, inspired us to embroider our thoughts at the end of the day.

During this activity, a group member pointed out how Peglar's square writing of his appointments allows us to map his travels, which resulted in them embroidering his travels on a map. We also tried our hand at backwards writing.

Comparing the Peglar papers to other material made them feel less weird: it grounded them firmly in their historical context, and put them in communication with a broader literary and epistolary culture. It let us imagine him not as a dying sailor huddling in the arctic, but as a living part of the expansive real world.

In our four sessions, we read most of the wallet. By the end we knew each other better, and could read difficult archival material with effortless confidence. We felt close to Peglar in a way that almost felt like touching him, which made us think about how we archive ourselves and our stories. We established a relationship with the past, close and full of affection, but also with each other. This is the whole point of the Queer History Club, and, I would argue, the entire point of studying history.

The plan for the near future is to revive the reading group, perhaps with a field trip to the Caird Library to see the papers in person. I also hope to run the workshop again, this time opening it to people outside the Queer History Club: what will bringing other people to the table allow us to see? What kind of necromantic or archival practices will their readings engender?