Find some fantastic night sky sights you can only catch in June - you won’t even have to stay up late for the best of the June sky to reveal itself!

Top 3 things to see in the night sky in June 2024:

- Throughout the month - eerie noctilucent clouds

- Throughout the month - stars of the Summer Triangle

- Throughout the month - the colourful Ring Nebula

(Details given are for London and may vary for other parts of the UK.)

Look Up! Podcast

Subscribe and listen to the Royal Observatory Greenwich's podcast Look Up! As well as taking you through what to see in the night sky each month, Royal Observatory astronomers pick two space news stories to talk about.

This month Jess and Imo talk through some of the month's must-see cosmic objects and discuss results from ESA's Euclid mission, as well as the misrepresented June 3rd planetary alignment.

Noctilucent clouds

Welcome to the most challenging month in stargazing, where thanks to the tilt of the Earth we will be working with the shortest nights of the year. The Sun won't set until around 9pm, and a level of twilight will remain throughout the night. On the 20th of June, many people will continue the ancient human tradition of marking the longest day of the year by heading to sites like Stonehenge. But we're here to talk about the night sky!

To make up for these nighttime limitations, there is actually a spectacular phenomenon only possible in the summer during astronomical twilight – noctilucent clouds.

Originating from Latin roots, the word noctilucent means 'night shining'. This perfectly describes these clouds which appear to glow after the Sun has set, creating a magnificent spectacle visible mostly as eerie silver-blue whisps. These clouds form higher than any other at 50 to 85 km in a layer of the atmosphere known as the mesosphere, where they are still able to reflect the Sun's light even after it has sunk below the horizon.

Clouds don't often form this high up. Noctilucent clouds consist of a combination of dust particles and ice crystals, which rely on the mesosphere to reach its coldest temperatures. This occurs during the summer near the poles thanks to atmospheric disturbances pushing cooled air upwards due to the summer warming of air lower down.

The presence of dust is even more rare at this atmospheric height. Unlike other atmospheric levels where dust can come from the ground, in the mesosphere the fine particles are provided by specific events such as micrometeorites, volcanic eruptions, and even rocket launches.

Not only are they only possible in the summer, noctilucent clouds are only visible between 45 and 80 degrees north and south of the equator, which luckily includes the UK. Keep in mind that the further south you go, the shorter the visibility period of these clouds will be as the Sun sets lower below the horizon. Look west towards a flat horizon about an hour after sunset for the best chance to spot this rare phenomenon.

The Summer Triangle

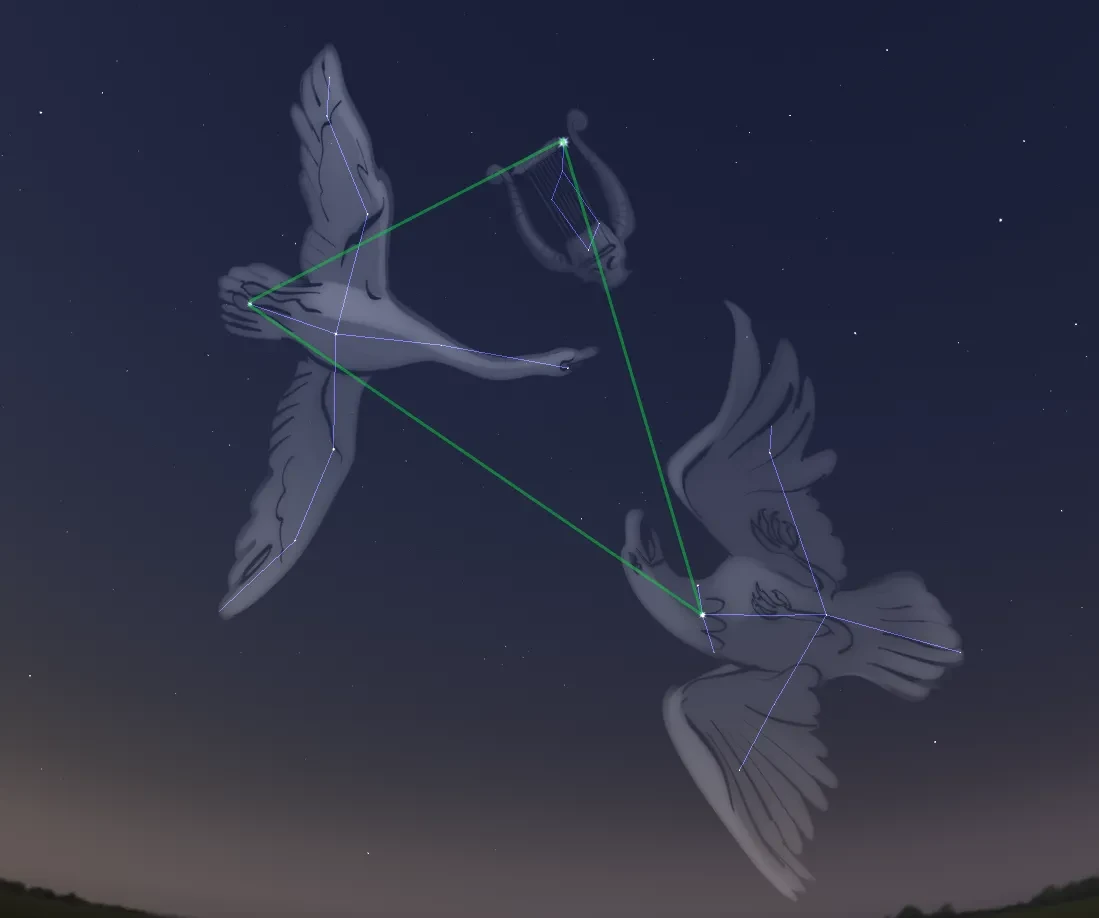

It wouldn't be summer observing without the Summer Triangle!

Hanging in the eastern sky, this is an asterism in the shape of- you guessed it- a triangle, formed from the brightest stars across three different constellations. Many constellations or asterisms date back many thousands of years. However, mentions of the Summer Triangle only started appearing in guidebooks just over a hundred years ago. This by no means makes it any less iconic. Deneb, Vega and Altair, the three stars making up the Summer Triangle, are some of the brightest in the night sky - making it well suited for summer observing when dimmer objects become increasingly difficult to make out.

Deneb

Deneb, meaning 'tail', represents the tail of the constellation Cygnus, the swan. Though it's the faintest of the three, in real terms Deneb outshines Altair and Vega once its 2.5 thousand light year distance has been accounted for. Deneb is a blue-white supergiant, an extremely powerful star likely on its way to the red supergiant stage of its life.

Vega

Not only the brightest in the constellation of Lyra, Vega is the 5th brightest star in the night sky. This very heavily studied star was the first target of spectrographic imaging and has been used as a calibrator to measure the photometric brightness of other stars. Like our Sun, Vega is about midway through the main sequence and is relatively close to us at just 25 light years away.

Altair

Altair forms part of the head of Aquila, the eagle constellation. It is the 12th brightest star in the night sky as it is one of the closest stars visible to the naked eye at a mere 16.7 light years away. Altair is a young main sequence star rotating so rapidly at over 210 km per second that it has flattened at its poles to form an oblate spheroid, like a tennis ball squished on opposite ends. This itself is not unusual, even all the planets in our Solar System are flattened somewhat due to their rotation, but the effect is so exaggerated on Altair it is an impressive 14% wider in diameter at its equator.

The Ring Nebula in Lyra

Once we’re looking in the direction of the Summer Triangle, we can take a closer look towards Lyra with a pair of strong binoculars or a telescope.

South of Vega, you can find the descriptively named Ring Nebula, also known as M57, the 57th Messier object, as discovered by Charles Messier in 1779. Around this time astronomers described M57 as resembling a fading planet, as well as theorising it was a collection of unresolved stars.

We now know the Ring Nebula to be the remnants of a star that was once not too dissimilar from our very own Sun.

Once an intermediate to low mass star has reached the end of its red giant phase, its outer layers spill out into the surrounding space. Remaining at the centre is an extremely hot, dense star known as a white dwarf. Viewing this star in the Ring Nebula is challenging and requires much more powerful telescopes than those required to spot the rings. Viewing the rings, however, is all thanks to this tiny central star, which emits ultraviolet radiation, ionising the surrounding gases, causing them to glow their distinct and beautiful colours. These colours paint a picture of the nebula’s chemical composition; blue, green, and red representing ionized helium, oxygen and nitrogen, respectively.

Planetary nebulae are some of the most gorgeous and varied art pieces the universe has to offer. The Ring Nebula appears to be one of the most symmetrical, but this is only due to our angle of observation. What appears to us as the central blue circle is actually the shape of a rugby ball, pointy end facing us, encircled by the outer red ring.

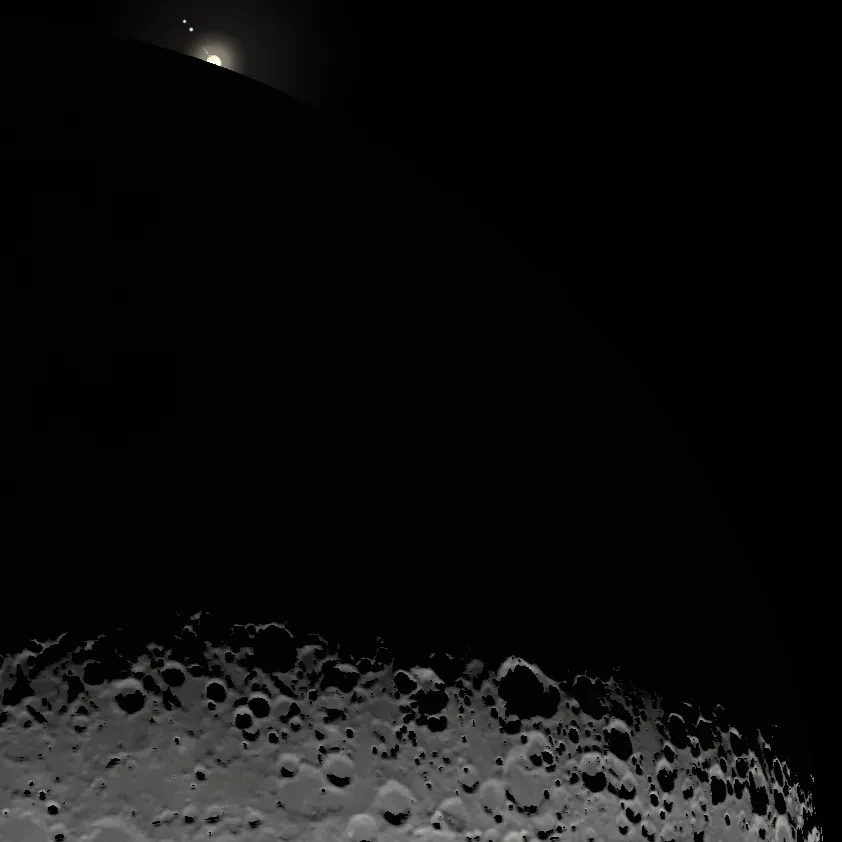

Lunar occultation of Saturn

On the 27th of June the Moon will appear to move in front of Saturn in an event known as a lunar occultation. People in eastern Australia, northern New Zealand, and other nearby areas will be able to see Saturn hide behind the Moon, reappearing after about an hour.

Lunar occultations are only visible from small parts of the globe at a time due to the proximity of the Moon, the same reason you have to be in the right place to catch a solar eclipse (which can also be described as a lunar occultation of the Sun).

If you are in the right place, you’ll want to look towards Aquarius, the water bearer, in the eastern sky. If not, you’ll still be able to see Saturn close by the waning gibbous Moon.

The Moon's phases in June 2024

New Moon: 6th June (12:38)

First Quarter: 14th June (05:18)

Full Moon: 22 June (01:08)

Last Quarter: 28 June (21:53)

Stargazing Tips

- When looking at faint objects such as stars, nebulae, the Milky Way and other galaxies it is important to allow your eyes to adapt to the dark so that you can achieve better night vision.

- Allow 15 minutes for your eyes to become sensitive in the dark and remember not to look at your mobile phone or any other bright device when stargazing.

- If you're using a star app on your phone, switch on the red night vision mode.

You may also be interested in

Header image: Webb captures detailed beauty of Ring Nebula (NIRCam image): ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, M. Barlow, N. Cox, R. Wesson