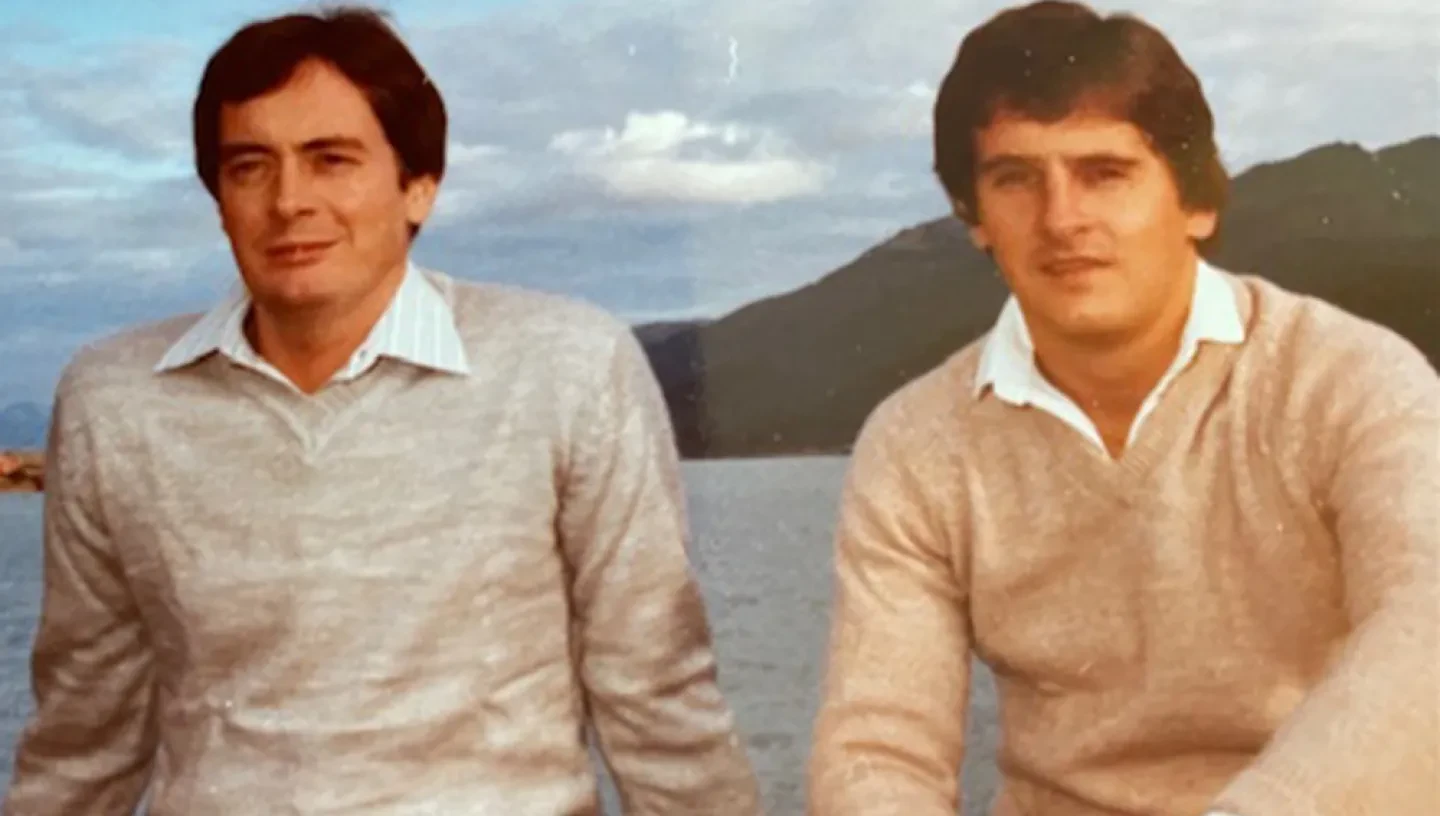

Michael and Dominic have shared their story with the National Maritime Museum as part of an ongoing oral history project, recording the experiences of people connected to, living or working at sea.

Donald Mullis, Curatorial Assistant (Oral History), takes up their story.

'Why don't you get a job on a ship?'

Michael Rudder’s parents were surprised when he told them that he wanted to work at sea. It was quite the change from his childhood upbringing: living on a farm in Enfield, a shop in rural Essex, a pig farm in Camberley before finally settling near Guildford in Surrey.

‘I had a very normal education. At school I took some “O” levels, but I wanted to take cookery,’ Michael recalls. ‘But I went to a boys’ school, and they didn’t teach cookery. They made enquiries at the girls’ school, and I took Domestic Science at the girls’ school.’

A hotel management and cookery course followed at Guildford Technical College, which Michael, to use his own words, ‘passed with flying colours’.

It was one of his teachers at the college who first suggested the idea of a career at sea. Michael recalls their conversation: ‘He said, “I tell you what boy, why don’t you get a job on a ship? I can help you. You’ll go away to sea, see the world, earn a few bob: you’ll love it.”’ I thought, “That sounds good.”’

The teacher gave Michael a glowing reference for his application with P&O, and he got his first job at sea at the age of 17.

‘My mother said to me, “Oh you’re joining the Merchant Navy”. I said, “Oh no, it’s nothing like that Mum, it’s a floating hotel and I’m going to be a waiter and afloat.” I was so naïve.’ Listen to the full clip below.

Dominic Brown's route was somewhat different.

He had grown up in an area of Belfast known as Sailortown, close to Belfast docks, and his father and other family members had already worked at sea.

‘I was brought up by my grandmother, who even lived in a street called Dock Street,’ he says.

As a result, Dominic's father's reaction to his son deciding to go to sea was very positive: he believed that it would expand his mind through meeting people across the country’s ports, at sea and around the world.

He found his first job on board a ship in 1969 aged 15 and a half, having left school at just 15.

Thrown in at the deep end

Michael’s first ship was the cruise liner Oriana sailing from Southampton.

'To go to sea and never have any training at all, I was thrown in at the deep end,' he recalls. 'I was absolutely petrified.

'But everybody was very kind and very helpful, and, you know, could see I was naïve and green.' Listen to the full clip below.

Dominic’s first voyage was on the cargo ship Port Montreal sailing from Liverpool. He started work as a deck boy, but because he didn’t attend National Sea School (which usually trained boys in maritime trades) he learned on the job. In order to rise through the ranks he would have to pass a test with the Board of Trade.

‘You had to learn all these knots, how to splice ropes and that type of thing because you had to go there and demonstrate that you could do this,’ he says. ‘And then you were given your EDH [Efficient Deck Hand] certificate, and you went away as a deck hand. And after so many months of that you’d go and get your Able Bodied Seaman, which was really respected, you know.’

Michael's working day with P&O would start at 6am. He recalls being woken with a cup of tea by the ‘peak boys’ – Indian ratings who supplemented their wages by looking after the crew. Their cabins were positioned at the bow or 'peak' of the ship, hence the name.

Work would start at 6.30am on the passengers’ breakfast. There were two sittings, one at 7.30am and the second about an hour later. Morning domestic jobs were followed by lunch service, afternoon tea, and dinner service.

Working days were long and Michael maintained this regular daily routine on passenger ships from 1969 to 1974, before moving to cargo ships for a special and personal reason which will become clear. His progression through the Merchant Navy ranks took him from deck boy to Able Seaman, and from cruise liner Oriana through Canberra and the QE2.

A typical working day for Dominic as a deck boy on cargo ships was eight hours long, with an expectation of regularly being required to do up to three hours' overtime.

For Dominic there wasn’t much to dislike apart from the long hours, and there was a lot to like, such as the general camaraderie on board ship and the extensive travel.

‘In them days if you wanted a pair of jeans you could go to the federation and get a ship to America where jeans were cheap,’ he says. ‘But ships changed from cargo ships in the 70s. I think I seen the last of the Merchant Navy properly, because containerisation was coming in, so a lot of cargo ships was actually getting scrapped.’

Dominic eventually left cargo to work on passenger ships, progressing to Bosun – which is how he met Michael.

In the bar of the 'Northern Star'

Michael and Dominic met in 1974. Michael was working on the cruise liner Northern Star and Dominic was working on the Oriana in Lisbon.

‘My cabin mate said to me, "Why don’t we go down to the Northern Star and have a drink at lunch time?"' Dominic recalls. ‘So we did. We went up to the crew bar, had a few beers and what have you. I’d seen Michael, and was attracted to him.’

They ended up going for dinner together on shore before returning to Michael’s ship.

‘I was in a four-berth cabin, but I shared it with other gays,’ Michael says. ‘We had curtains all alongside the side of the bunk for privacy, so if you wanted to “entertain a gentleman...”’

Staying on the Northern Star overnight, Dominic missed the departure of his own ship in the morning and spent some time in the ship’s prison accused of being a stowaway.

It was left to Michael to speak with the captain.

‘I knocked on the door and he said, “Oh hello Michael, come in,”’ Michael remembers. ‘I said, “Erm, you must know that I’ve accidentally stowed away a friend of mine on here,” and he said, “Ah, yes, I know all about it Michael.”’

The captain quickly reassured Michael that neither of them would be in trouble as a result. Listen to his full account below.

Dominic and Michael both feel that there was more acceptance of gay people at sea in the 1970s and early 80s than there was ashore.

‘"Shoreside people" as we call them, their attitude was probably old-fashioned,' Dominic says. ‘At sea it was always “live and let live”’.

Michael adds, ‘I knew I was gay at an early age, about 14, but of course I couldn’t do anything about it in those days because it was against the law until 1967. And even after the new law came in it was still taboo.

‘But when I got on the ship I could see there were some gay people on board who couldn’t care less who knew they were gay, made it quite obvious! And it was quite a learning curve, and lovely: people just accepted everybody else.’

Their life at sea was fun and enhanced further with the use of the secret gay language Polari, a form of slang that allowed gay men to subtly identify each other while making themselves unintelligible to those outside their community.

After the stowaway incident, both Michael and Dominic’s ships docked in Southampton on the same day. They completed their individual contracts before signing on together on a BP tanker called the British Merlin.

There followed a period of working together on the same ships but also apart on different ships until they both retired from life on the sea in the mid-1980s. They then started a successful bus company until they both retired from four wheels in the mid-2000s.

Michael and Dominic ‘tied the knot’ on 21 December 2014, the same day as Elton John and David Furnish – nine months after same-sex marriage took effect in England on 29 March that year.

Elton and David now live happily in any number of homes. Michael and Dominic live happily in the landlocked town of Shirley in the East Midlands.

In June 2025 Michael released his first book of recollections of his life at sea, Anything Goes at Sea: A Gay Seafarer’s Memoir, published by The Book Guild. For more details, visit Michael’s blog at anythinggoesatsea.com.

The recordings featured in this story are part of an ongoing oral history project at the National Maritime Museum. The project intends to record people's experiences at sea and memories of maritime events. If you think you may have a story to share, email research@rmg.co.uk. Please note that the team is small so may not be able to respond immediately.