When you walk into an art gallery, what do you see? Paintings and drawings of course, probably the information labels – but do you notice the frames? Do you consider the light levels and hanging heights, wonder about how artworks are actually fixed to the wall, or even think about how all these works get through the doors in the first place?

If you're not thinking about these things, that's probably a good sign: it means you can enjoy the art and the space free from distractions. But it also means that so much of the work that goes into creating an exhibition goes unnoticed and underappreciated.

Every year the Queen’s House closes in order to prepare for exciting new displays. In 2024, I went behind the scenes to find out what happens while the doors are shut.

‘It’s mental gymnastics in a way: you want to tell a story about the art collection we hold, tell a story about the history of the building, and try to find ways to make those two things speak to one another’

Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art

The first task in choosing what to hang from the thousands of artworks held by Royal Museums Greenwich falls to the curatorial team.

“I think one of the most distinctive challenges about preparing for a display at the Queen’s House is the fact that you’re working within a historic house, but you’re not working with a collection that is intrinsic to that house,” explains Dr Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art (Post-1800).

“With other historic houses, typically most of the collections will have once been bought or made specifically for those spaces. Whereas we have a house that has its own amazing story, but none of the original furnishings remain.

“We obviously can’t go about knocking down walls or installing a goods lift, so we have to work within the unique architecture of the building,” Katherine continues. “It’s like playing a game of Tetris, trying to get all of the paintings we want to fit.”

Those physical constraints however can offer up intriguing opportunities when it comes to choosing what to display.

“As art curators we talk a lot about ‘vistas’. If you’re looking through a doorway or walking into a room, what’s your line of sight? What’s your vista? It’s about using the natural framing devices of the architecture, encouraging visitors to peer further in and keep walking to see what’s next.”

It is this ‘dialogue’ between building and artwork, Katherine suggests, that is core to a Queen’s House display: “One of the prints we selected for display in 2024 for example was a woman on parade, satirizing an 18th century fashion for oversized bonnets. She is seen walking along the borders in Greenwich Park, with the Royal Observatory behind her. It was displayed in a room where, were you to look out the window, that’s exactly the view you would see. It was beautifully site specific.”

First-time visitors to the Queen’s House may not realise that what is on display is always changing. Historic items are conserved, new artworks are acquired, and research throws up fresh ways of seeing the collection.

“We only ever display a tiny, tiny fraction of the entire collection,” explains Katherine. “A rehang is a chance to highlight some of the discoveries – and rediscoveries – that research throws up.

“The collection keeps growing, new research is happening all the time, the Queen’s House is never static; we don’t want to get into a situation where we have a list of the ‘best’ paintings which are always on display and nothing changes.”

That said, it’s not quite as simple as a curator browsing the stores and picking out whatever they want to go on a wall.

‘Conservators are privileged to be able to work more closely with objects than almost anyone else. The only downside is, when it finally goes on display, all you can see are the details – you forget to stand back and take it all in!’

Francesca Whymark, Senior Manager, 2D Conservation

While a curator may develop an initial list of works for an exhibition or gallery, it is the role of museum conservators to prepare them for public display.

"It’s a compromise between the needs of curatorial and the condition needs of the object," explains Francesca Whymark, Senior Manager of 2D Conservation. "We received an initial longlist of more than 90 new objects including paintings, drawings, prints, textiles and 3D objects for this display. We had to reduce that a little bit due to the condition of some of the objects, which could not be treated in the time available. Full conservation treatment can only be carried out on a small number of objects as this kind of work takes time."

Perhaps most high profile of these conservation projects was a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough, the rediscovery of which prompted a fundraising campaign to preserve the painting for future generations. But the Gainsborough portrait is just one task in a rehang requiring many skills and specialisms.

“The conservation team includes 21 staff who specialise in conservation of paintings, frames, textiles, paper and books, metals, ceramics and glass, horology, wooden and organic objects, preventive conservation and shipkeeping,” says Francesca.

Most of the paintings earmarked for display in the Queen's House are in historic frames, which are objects in their own right and also require conservation treatment. Textiles, books and 3D objects all require bespoke mounts, while works on paper and some textiles are framed for display. The conservation team includes specialist technicians, who work alongside the conservators to construct these mounts.

Other crafts also come into play, such as the welding skills of one of the shipkeepers on board Cutty Sark, who has been helping to fabricate supporting brackets for some of the largest and heaviest paintings.

Much of this work is carried out in the controlled conditions of the Prince Philip Maritime Collections Centre, a state-of-the-art conservation and storage facility. Once an object goes on display however, a new series of conservation challenges arises.

"Objects are always at greater risk while on display,” says Francesca. “Light is a particular issue for works on paper. Everyone will probably have experience of something being left near a window and seeing it fade as it’s exposed to the light."

The windows in the Queen’s House have UV filtering film and blinds to control the light, while some shutters will be closed completely. Sensitive materials, such as paper, can only be displayed at a low light level and for a maximum of 12 months in any 10-year period.

Objects on open display also collect more dust: the team will carry out regular conservation cleaning of objects throughout the House.

Conservators, like curators, need to work within the physical constraints of the House.

“The Queen’s House is a historic building and scheduled ancient monument,” says Glen Smith, Senior Manager, 3D Conservation. “We use conservation heating which allows us to maintain a stable relative humidity in the range of 40-60%.”

Relative humidity means the percentage of the total amount of moisture the air can hold at a certain temperature. When relative humidity reaches 100%, the air cannot hold any more water vapour and condensation occurs – like when you get into a car on a cold day and the windows steam up.

Objects can be damaged if the humidity is too high or too low, as well as by large fluctuations in relative humidity. Some particularly sensitive objects are displayed in cases, and the majority of paintings are glazed and include a backboard to create additional protection.

Measures such as these allow visitors to enjoy the works on display while also ensuring the collection is preserved. But how do objects actually get from the stores to the gallery walls?

‘Being an art object handler means my experience of art exhibitions can be slightly ruined. I end up more interested in what kind of hanging systems they use – it can earn me strange looks from security guards!’

Antonia Mavromatidou, Collections Logistics Manager

One of the most important jobs during an exhibition install falls to the art and object handling team: the people tasked with packing, transporting, carrying and hanging all the works visitors see around the gallery.

Think about the last time you moved house. Did everything go safely into the van? How easy was it to get through the doors? Did everything fit and fix as you expected? Multiply that by 100 and you have some idea of the logistical challenges that art and object handlers face.

“Preparation is key, whatever type of object you're going to be working on,” explains Collections Logistics Manager Antonia Mavromatidou. “This rehang is mainly 2D objects – drawings and paintings – so we need to make sure we have the right equipment in the right place on the right day. But you also need to have thought through all the little details like fixings and hanging systems, wall materials and door heights.

“For particularly tricky paintings, we’ll prepare method statements in advance, just so everyone is clear how the install will happen: how many people are needed, who’s going up the ladders, who’s handling the stacker truck. It is like a dance – everyone needs to be coordinated for it to go smoothly.”

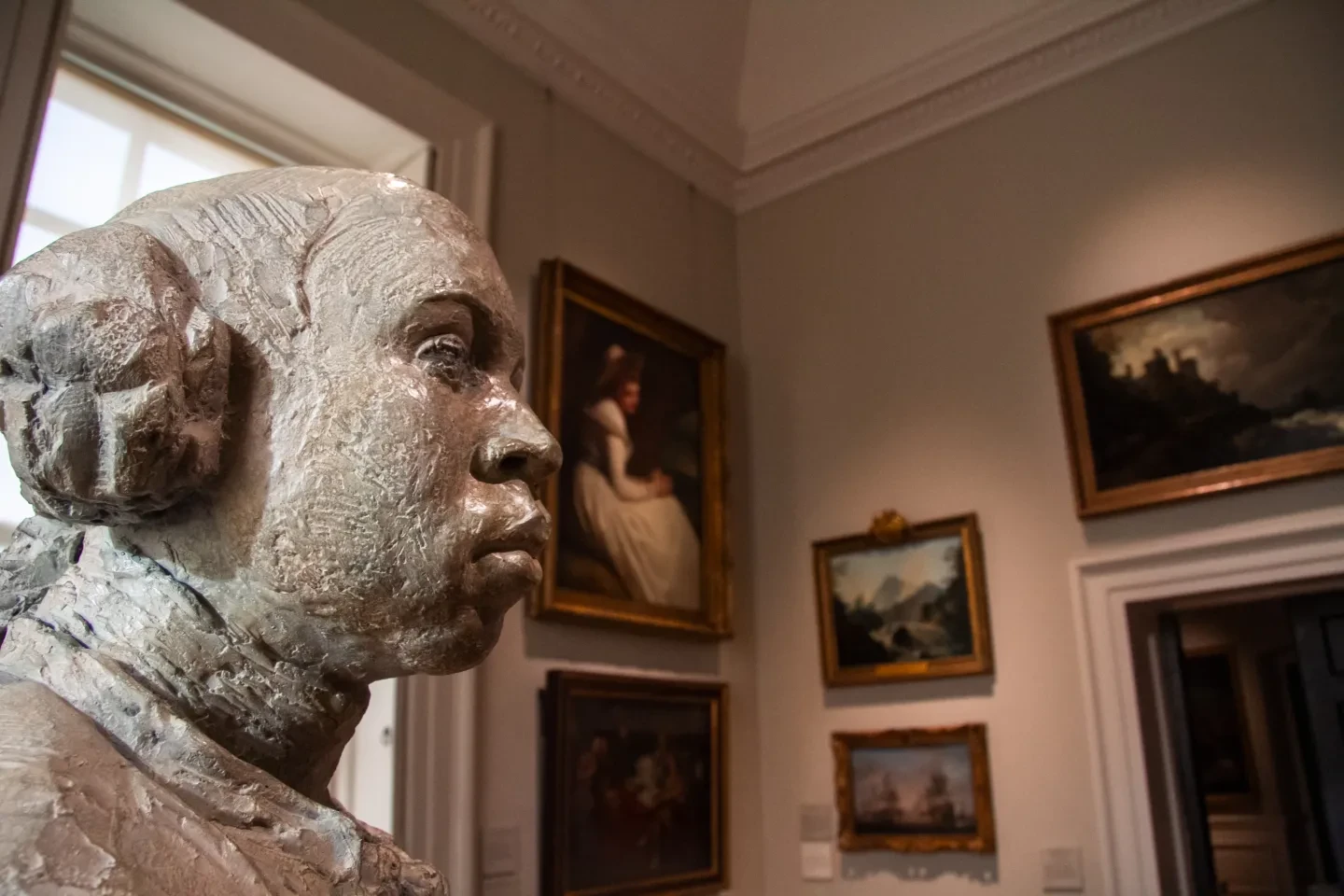

The Queen's House display in 2024 included 127 separate object moves, from paintings and drawings to woodcarvings, sculpture and even items of clothing. This is where all the different specialisms come together.

“During installation a curator’s role is essentially to answer one question: ‘Is it straight?’” laughs Katherine. “I suppose in some ways I’m there as the visitor’s proxy: trying to figure out whether the display looks and feels right, and what the eye will be drawn to once the room is complete.”

Keeping things straight is easier said than done in the Queen’s House however.

“The spirit level will tell you that it’s hanging perfectly, but then you take a step back and it just doesn’t look right,” says Antonia. “Your eye sees it differently, plays tricks on you. That’s where you need the curator’s input.”

“That said,” adds Katherine, “there are definitely times when I need to shut up and let the handlers get on with it…”

At over three and a half metres wide, the painting A Royal Visit to the Fleet in the Thames Estuary was so large that it could not be moved up and down stairs in one piece. Conservators therefore removed the frame, art handlers carried both frame and painting separately through the galleries, then conservators reframed the painting in the room just before handlers lifted it into place. Next time you see a large-scale painting hanging in the House, spare a thought for the people who moved it there in the first place.

It is not only the large objects that come with challenges. A portrait of an (as-yet-unidentified) Wren officer appears unassuming at just 55cm high, but because the portrait was made in pastel, the slightest movement could have damaged the fragile medium.

"Pastel consists of very finely ground pigment, and a white filler such as chalk. There is almost no binder, meaning there’s nothing holding the pigment on the page. For this reason, pastels are always framed under glass," says Francesca. "Pastels are also quite sensitive to changes in humidity, so it will be mounted within a sealed package, with some modifications made to the original frame, allowing us to enclose the whole safely within."

The pastel was transported horizontally in a padded box to limit vibration. For both Antonia and Katherine, it’s this kind of work that underlines the care that goes into a Queen's House display.

“We are conscious of our shortcomings and the stories we are not representing,” Katherine says. “We already had a room full of wartime portraits, but until now it’s been almost entirely men represented. Being able to add this woman in a naval role adds hugely to that display.

“The wall is covered as high as you can see with portraits; we are positioning her in the bottom left-hand corner,” she adds. “Partly that’s because it gives her a real prominence: she will be at eye level, right opposite the door, an anchor point for the whole display.

“But that position also means nobody needed a ladder to hang her. It was a helpful alignment between what is practical and manageable, and also truly impactful. I think that’s how I got away with it!”

“The Wren was a new acquisition, and I always love being able to display new objects,” adds Antonia. “I love to be able to bring something out of storage and onto public display: the more we can share with visitors, the better.”

See it for yourself

Art in your inbox

Sign up to our newsletter to discover more great stories about art, culture and the collections of Royal Museums Greenwich