Water courses through the works of William Shakespeare.

The sea carves out plots, turns the tide on characters' fates, and acts as a device for exploring a range of human emotions and experiences. Even in plays and poems not set by or on the water, tumultuous seas, shipwrecks, and maritime life still seep into Shakespeare's language.

The National Maritime Museum has assembled an international group of Shakespeare academics, authors, creators and directors. Each has selected one Shakespeare passage that draws on the language of the sea, teasing out the meaning behind the maritime allusion.

Keep scrolling to explore the whole list, or click the links below to jump straight to your favourite passage.

'Methoughts I saw a thousand fearful wrecks' - Richard III

'These roguing thieves serve the great pirate Valdes' - Pericles

'Ere we were two days old at sea, a pirate of very warlike appointment gave us chase' - Hamlet

'Keep your cabins! You do assist the storm.' - The Tempest

'There is a tide in the affairs of men' - Julius Caesar

'You will hang like an icicle on a Dutchman’s beard' - Twelfth Night

'But he that hath the steerage of my course direct my sail' - Romeo and Juliet

'Full fathom five thy father lies' - The Tempest

'Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea' - Pericles

'Lie where the light foam of the sea may beat thy gravestone daily' - Timon of Athens

Methoughts I saw a thousand fearful wrecks;

Richard III, Act 1 Scene 4

Ten thousand men that fishes gnaw’d upon;

Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl,

Inestimable stones, unvalu’d jewels,

All scatter’d in the bottom of the sea.

Some lay in dead men’s skulls, and in the holes

Where eyes did once inhibit, there were crept –

As ‘twere in scorn of eyes – reflecting gems,

That woo’d the slimy bottom of the deep,

And mock’d the dead bones that lay scatter’d by.

This violently beautiful passage occurs in Act 1, Scene 4 of Richard III. Richard’s brother George the Duke of Clarence is imprisoned inside the Tower of London on suspicion of treason against his brother, Edward IV. Clarence tells the Constable of the Tower, Sir Robert Brackenbury, about a vivid and disturbing dream he had the previous night.

In his dream, Clarence has broken from the Tower to cross to Burgundy with Richard. Richard entices Clarence up on deck, stumbles and pushes him overboard into the “tumbling billows of the main” (1.4.20) where he drowns a painful and prolonged death. The passage is prophetic—shortly afterwards, Clarence is stabbed and drowned in a barrel by assassins sent by Richard.

Shakespeare frequently employs the sea as a deadly force separating characters (Twelfth Night, The Comedy of Errors, Pericles) or splitting ships to ruin (The Tempest, Merchant of Venice). In an age of maritime exploration and expansionism in which the island nation relied heavily on the sea, drowning was a present danger.

What is particularly interesting about this passage is its peculiar juxtaposition of imagery. Alongside bones, gnawing fish and slime are gold, pearls and gems. These are not merely sprinkled but abundantly piled in dazzling opulence with “Wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl” (1.4.26). The image is horrific in its splendour—eyes are replaced with glimmering “reflecting gems” (1.4.31) and riches become sickening.

The passage embodies the play’s brutal thirst for the crown. Shakespeare’s sublime language also evokes the sea’s exquisite treasures and reminds us of its power. There is, however, another way to consider the text within our own era of material excess. Piled with once-valued refuse, the ocean, like Clarence’s dream, offers us a grim warning.

Dr Alys Daroy is Lecturer in English and Theatre at Murdoch University in Western Australia and Founder of biophilic eco-theatre company Shakespeare South.

These roguing thieves serve the great pirate Valdes;

Pericles, Act 5 Scene 1

And they have seized Marina. Let her go:

There's no hope she will return. I'll swear she's dead,

And thrown into the sea. But I'll see further:

Perhaps they will but please themselves upon her,

Not carry her aboard. If she remain,

Whom they have ravish'd must by me be slain.

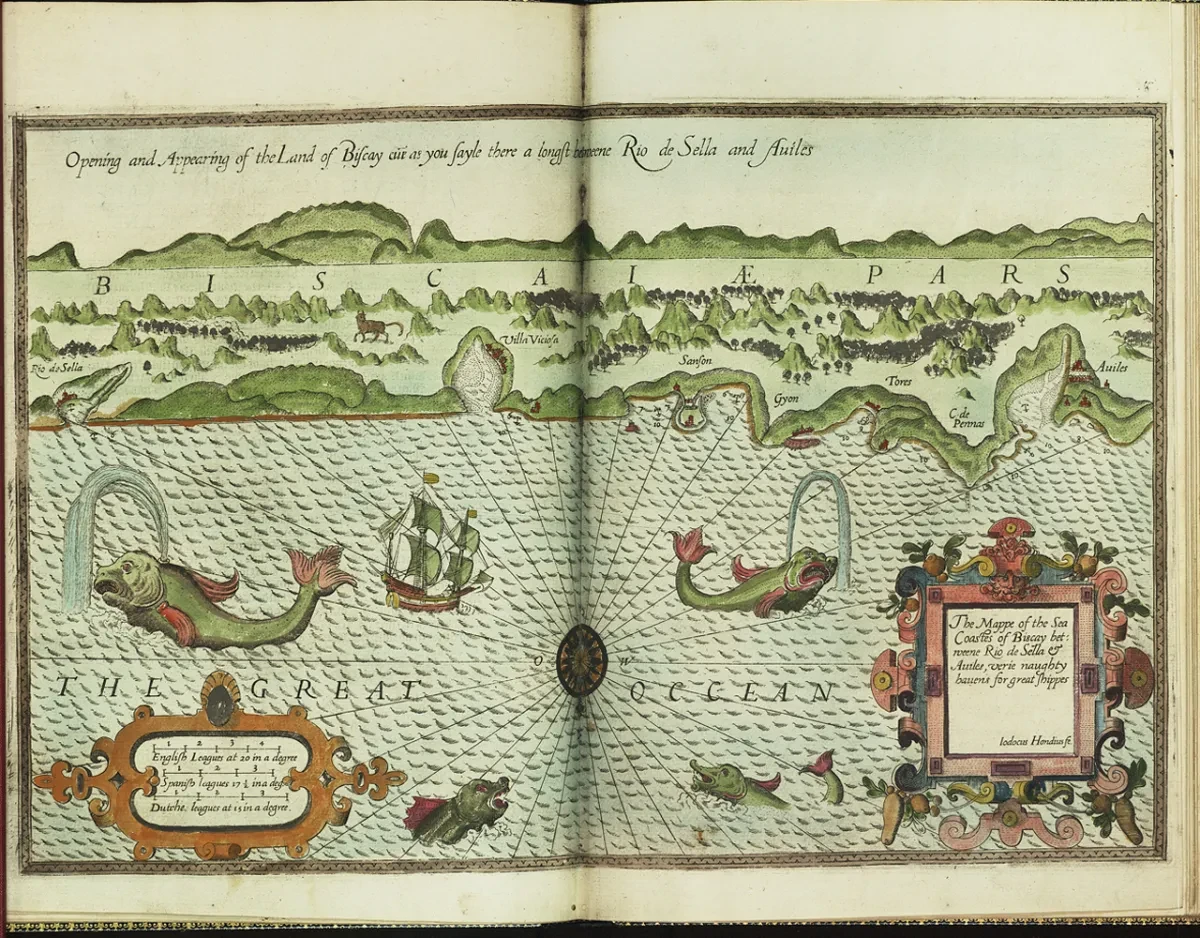

In the decades that followed the Spanish Armada of 1588, England managed to win the war of propaganda before an international audience: the Spanish were presented as a decadent power, and England as providentially destined to occupy their position of privilege.

The English fleet managed to capture only one Spanish ship during the opening skirmishes of the Armada, a vessel commanded by Pedro de Valdés. It is more than likely that his captor, Sir Francis Drake, gathered from him relevant information about Philip II’s secret plans while the battle was still in progress. Back in England, and for the three years that his imprisonment lasted, Valdés became the target of some prominent English propagandists who willingly assumed the task of undermining the prestige of Spain, both as a colonial and as a military power.

Valdés became both an emblem of Spanish perfidy and a harbinger of Spain’s ultimate defeat in favour of the English. This is precisely what William Shakespeare is doing in the play Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1608-9), where he does not hesitate to turn Valdés, one of the leaders of the Spanish Armada, into a vile pirate who first captures and then sells the heroine Marina to a brothel.

Unknowingly though, by doing this Valdés becomes the saviour of Marina, and the one ultimately responsible for the happy resolution of this celebrated Shakespearean romance.

Francisco J. Borge is a Senior Lecturer in English Language, Literature, and Culture at the University of Oviedo (Spain).

Ere we were two days old at sea, a pirate of very warlike appointment gave us chase.

Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 3

Finding ourselves too slow of sail, we put on a compelled valour and in the grapple I boarded them.

On the instant, they got clear of our ship, so I alone became their prisoner.

Chances are this isn’t the first quotation that comes to mind when you think of Hamlet. But this cool, beautiful piece of prose records what is arguably the most decisive event in this famously indecisive play.

Sent by sea to his death in England after confronting his uncle Claudius with a re-enactment of the murder of his father, Hamlet escapes the supervision of erstwhile friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in a skirmish with pirates. He returns with them to the coast of Denmark, and the sailors deliver letters on his behalf announcing his return to Claudius and Horatio. Both letters are read out on stage, in successive scenes.

The first, to Horatio, recounts this rather exciting episode from the swashbuckling thriller Shakespeare never wrote - though there might have been something like it in the play Tom Stoppard imagines him trying to write in the film Shakespeare in Love: 'Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate's Daughter'. Instead, he meets Viola de Lesseps and gets the inspiration for Twelfth Night, a play that similarly owes its plot to the kindly offices of a friendly pirate.

Twelfth Night and Hamlet were written within a year of each other in the last years of Elizabeth’s reign, 1600-1601, when the exploits of Elizabethan seadogs such as Francis Drake (pictured) and Walter Raleigh would have been well enough known to help Shakespeare keep his audience on the edge of their seats, even in a scene in which absolutely nothing happens except a man standing on stage reading a letter.

Erica Sheen's work on Shakespeare includes Shakespeare and the Institution of Theatre: The Best in this Kind (Palgrave 2009); Shakespeare in Cold War Europe: Conflict, Commemoration, Celebration, co-ed. with Isabelle Karremann (Palgrave 2015), and a forthcoming monograph, Geopolitical Shakespeare (OUP 2023). She teaches in the Department of English and Related Literature at the University of York.

Boatswain: You mar our labour.

The Tempest, Act 1 Scene 1

Keep your cabins! You do assist the storm.

Gonzalo: Nay, good, be patient.

Boatswain: When the sea is. Hence! What cares these

roarers for the name of king? To cabin! Silence!

Trouble us not.

Gonzalo: Good, yet remember whom thou hast aboard.

Boatswain: None that I more love than myself.

Shakespeare’s skill as a playwright is not only demonstrated in beautiful words, witty dialogue, and exciting dramatic plots—it also reveals a deep knowledge of how people really worked and lived in early modern England.

The opening scene of The Tempest shows the audience how skilled mariners respond to the deadly threat of extreme weather. The scene presents a clash of two social classes: the commoners who perform the hard work of sailing, and the idle aristocrats and King of Naples who are passengers returning to Italy from Africa. While the mariners endeavour to control the ship and keep it afloat, the frightened blue-bloods only get in the way. All of their power and social superiority melts away in the face of Nature’s greater power.

It is a scene, in a play about power and knowledge, that reveals the limits of upper-class power when it depends on the labour-value provided by workers. And in this case, it depends quite desperately on the skills of the sailors and their officers, the working men who run the ship.

The normal protocols of obedience and deference to aristocratic power are simply no longer pertinent when survival is at stake. Here, the language is plain prose, declaimed in curt syllables over the roar of the wind and waves. And yet, these are carefully crafted lines that use a strong rhythm and a sibilant consonance (for example, in "You do assist the storm") to accentuate the urgency of this shouting above the roar of winds and crashing waves. The simple language expresses a basic, proverbial truth: Nature is a great leveller; it is social-class hierarchy that is “unnatural.”

And yet a further complexity is revealed in the next scene—this storm was not 'natural' at all. It was raised by Prospero, whose knowledge of magic allows him to manipulate Nature herself through the elemental spirits he controls.

Daniel Vitkus holds the Rebeca Hickel Endowed Chair in Early Modern Literature at the University of California, San Diego, and is the author of Turning Turk: English Theater and the Multicultural Mediterranean, 1570-1630 and numerous articles and book chapters on early modern literature and cultural history.

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Julius Caesar, Act 4 Scene 2

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

This moment in Julius Caesar is rich in imagery, music – and irony. Here, the cyclical pattern of the Wheel of Fortune familiar to Shakespeare’s audience becomes a tide, rising and ebbing outside of Man’s control, which must be seized at the opportune moment or missed forever.

The two forces of choice and destiny meet in the scales at this point: the tide will rise and fall whatever we do, but we can act, asserting our will within this greater cosmic balance. The contrasting images reflect this: first a ship cresting the waves at their height, evoking the excitement of Elizabethan seafaring and exploration, then the mirror-image of being ‘bound in shallows’, which suggests the stymieing of movement, foundering on England’s treacherous sands.

Shakespeare builds a mesh of sound to contain this moment: the natural rise and fall of the vowels’ inflection in ‘tide’ and ‘affairs’ reiterate the tide’s cycle, given extra force in the alternating length of short and long vowel-sounds (‘tide in’ and ‘affairs’) that tug the audience onward. Meanwhile, the fricatives throughout echo the hissing rush of the sea, the alliteration of ‘flood’ and ‘fortune’ suggestive of the swelling tide, doubling in height, shifting to more treacherous sibilance as the ship becomes stuck.

Shakespeare’s structure is also telling: the heavy use of caesura and end-stopping in the first two lines suggest control, but the enjambment of the final two lines suggest the slipping away of opportunity, leading inevitably to that final, end-stopped ‘miseries’. At this moment, as Brutus eagerly urges Cassius (despite his consistently better judgement) to commit to a final, fateful battle at Philippi, the audience knows the conspirators’ forces will fall to those of Antony and Octavius. Their destruction is fixed, and Brutus’ belief in their ability to affect their fate rings, therefore, with tragic irony.

Emily Green studied English Literature at undergraduate and Master’s level at the University of Durham, and now teaches English to teenage boys at The City of London School. She is currently undertaking a MSt in Creative Writing at Oxford University.

The double gilt of

Twelfth Night, Act 3 Scene 2

this opportunity you let time wash off, and you are

now sailed into the north of my lady’s opinion, where

you will hang like an icicle on a Dutchman’s beard un-

less you do redeem it by some laudable attempt either of

valour or policy.

Midway through Twelfth Night, Fabian teases the hot-blooded Sir Andrew Aguecheek, telling him that he has “now sailed into the north of my lady’s opinion, where you will hang like an icicle on a Dutchman’s beard unless you do redeem it by some laudable attempt either of valour or policy” (3.2.24-27). Like the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz (pictured) in his hapless Arctic exploration, Sir Andrew’s endeavour in pursuit of Olivia has run aground and become caught in the ice of her frozen demeanour, where he will be forced to winter unless he frees himself by a heroic masculine effort.

Barentsz was well known in Shakespeare’s time for attempting a north-east passage by sailing directly toward the North Pole. He and his crew were forced to winter north of the Arctic Circle, miraculously returning to Amsterdam dressed in frozen Russian garb. Fabian’s reference places Sir Andrew’s attempt in the lexicon of the voyage narrative in which masculine achievement was measured by survival on hostile seas.

While early modern voyage narratives provided a dubious model of masculinity for English gentlemen to perform, Shakespeare also uses Fabian’s remark to poke fun at those European explorers who sailed off into the far north in order to test themselves. In Twelfth Night, Sir Andrew has as much of a chance of wooing Olivia as Barentsz did in navigating a sea passage across the North Pole. Fabian mocks the masculinity of Sir Andrew, who has been sent off to prove himself in a location far from the object of his affection.

Frozen seas in Shakespeare’s language often obstruct characters’ expectations, revealing early modern associations, reaching back to Virgil’s time and forward to our own, of wildness and incivility in regard to the coastal peoples of the Far North, depicted as non-English with rough icicles hardening on their unkempt beards.

Dr. Owen Kane is a SSHRC postdoctoral research fellow at Brock University in Canada, researching seventeenth-century English and Canadian Arctic contact literature.

But he that hath the steerage of my course

Romeo and Juliet, Act 1 Scene 4

Direct my sail.

Romeo says this in Act 1, Scene 4 of Romeo and Juliet, just before he and his friends Benvolio and Mercutio sneak into the Capulet party. Having stated that his "soul of lead" pins him immovably to the ground, and then that "Under love’s heavy burden do I sink", he shifts from a stubborn landlocked perception of his lovelorn state to a maritime metaphor: his life as a ship on Destiny’s seas, paralleling human ontology to the natural environment as his friends unconsciously lure him to the event that begins his end.

Who is the ‘he’ that steers his course? Is this figure God, or Fate? Is Romeo making a sarcastic analogy between these entities and one or the other of his friends forcing him to go to the party, or is it simply himself? Depending on how you stage it, any of these can be true, allowing for vast interpretive liberty. When you consider the element of fate in Romeo and Juliet, a play pre-scripted by its own prologue, Romeo’s submission to its power becomes significant; by conceding himself to be a human vessel on the waters of life, his metaphor of steering is an unknowing truism of the all-encompassing fate that governs the play; an unconscious, quiet but powerful yielding to the love and death that reconciles the two families.

In the end, Romeo does sink under love's heavy burden, but one might argue that his ship is destined to fail — the ‘course’ that it has charted for him is not one with a happy ending.

Annabelle Higgins is a 17-year-old writer, director, performer and young scholar who hosts the podcast A Teenager’s Take on Shakespeare.

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

Sonnet 60

So do our minutes hasten to their end.

The opening lines of Sonnet 60 present Shakespeare’s sea as a conceptual space, rather than a geographical one – likening the waves relentlessly making towards the shore to the fleetingness of human lifetimes, thus blurring together spatiality and temporality, and establishing a parallel between maritime imagery and death.

The sea and the land meet in rich metaphorical spaces, foregrounding transience and liminality. These images invite readers to contend with the discomfort of the indefinable, through exploring the everchanging spatiality of the ocean – the shore is the terminus of the sea, but still inextricably connected to it, just as death is by necessity linked to life. The human dream of truly conquering the sea – though said conquest presents a constant, dangerous and ultimately impossible endeavour, rather than an accomplishable goal – is equated with the pseudo-immortality that Shakespeare’s speaker imagines might be granted to both him and his love through literary greatness.

Attempting to stop time might be as futile as trying to stop the sea from reaching the shore, but it is precisely through this struggle – through the exploration of boundaries, pushing of limits, and a desperate striving for the impossible, all stemming from the human unwillingness to accept inevitability – that great accomplishments are made possible, and new spaces are opened up.

Theodora Loos is a postgraduate English Literary and Cultural Studies student, focusing on maritime literature at the University of Regensburg, and currently studying abroad at Auckland University.

His mother was a votaress of my order:

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act 2 Scene 1

And, in the spiced Indian air, by night,

Full often hath she gossip'd by my side,

And sat with me on Neptune's yellow sands,

Marking the embarked traders on the flood,

When we have laugh'd to see the sails conceive

And grow big-bellied with the wanton wind;

Which she, with pretty and with swimming gait

Following,—her womb then rich with my young squire,—

Would imitate, and sail upon the land,

To fetch me trifles, and return again,

As from a voyage, rich with merchandise.

But she, being mortal, of that boy did die;

And for her sake do I rear up her boy,

And for her sake I will not part with him.

My favourite passage in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, infused with the sea, brings a reflective pause to the action, re-focussing our attention on the warmth of female friendship between Titania, the Queen of the Fairies, and her votaress. In place of competition and aggression, a nostalgic serenity is evoked through sensuous images taken from the simple pleasures of life: sitting on the sand, taking in the night air, breathing in the heady scent of spices, gossiping, laughing, and watching merchants setting off on their long sea voyages.

The state of pregnancy is described in a remarkable image of lightness: a sail, billowing, swelling, and brought to full capacity for life through the power of the amorous wind. Subtly underscoring the dreamy atmosphere is the use of sibilants that dot the passage: spiced, gossiped, side, sat, sands, sails, swimming, squire, trifles, sake.

The “But” signals the abrupt change in mood with a poignant reminder of the mortal perils of labour. The anaphora (the repeated phrase of the last two lines) brings the whole reverie to an end with an assertion: Titania will not give up the “young squire”, the physical reminder of the bond of friendship, the “riches” brought to “port”.

The extraordinary interpenetration of sea and land through image, metaphor, and internal rhyme (Marking – embarking) emphasizes England as a maritime mercantile state. Neptune rules the shores as well as the sea. The votaress not only deliberately imitates the sailing ship in her appearance but also in her actions: her “swimming” gait suggests gliding, smooth movements. The “trifles” she brings back to Titania are likened to the merchandise of traders returning from their hazardous sea travels. Hovering occluded in the background is Queen Elizabeth I, who encouraged – sometimes actively, sometimes surreptitiously – exploration and piracy in the pursuit of power and supremacy on the seas. The far-distant, exotic India was one of the great prizes that beckoned.

Professor Irene (Irena) R. Makaryk, Distinguished University Professor, University of Ottawa, Canada, is currently working on her next book project, Arts for Survival: Performative Strategies and the Search for the Lost Franklin Expedition.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them—Ding-dong, bell.The Tempest, Act 1 Scene 2

I chose this quotation in honour of my ancestor, William Strachey. His first-hand eyewitness account as a shipwreck survivor of The Sea Venture, which ran aground off the coast of Bermuda, formed the basis of The Tempest. The fourth, fifth, and sixth lines of the quotation are particularly moving as he became a castaway in Bermuda for 10 months, before he was travelled to Jamestown, Virginia after constructing two small vessels ‘Patience’ and ‘Deliverance’.

The "sea change" refers not only to the shipwreck but Strachey’s metamorphosis as a man moving from tragedy to triumph (and tragedy again). The quote "something rich and strange" refers to Shakespeare’s rich legacy as one who was inspired by Strachey’s account to produce The Tempest, which formed part of a portfolio of work which has sold more than four billion books worldwide – yet few know of Strachey as an unknown writer, who struggled for 10 years to get his writing published in London.

Strachey became the secretary and recorder of Jamestown under Lord De La Warre, recording the exploits of Pocahontas and was one of two historians to record the indigenous language of the Powhatan people. However, he died in abject poverty in London in 1621 after speaking out about the harsh conditions of Jamestown under the British government.

Lying in a pauper’s grave on the grounds of St Giles, Camberwell, the ‘ding-dong bell’ conjures up the image of the church bell of St Giles ringing after the end of service.

Lynsey Ford is a journalist, librarian and researcher, having written for publications including Discover Your Ancestors, The Museums Journal, The British Film Institute and The Arts Newspaper. Lynsey is also a Fellow of The Royal Society of Arts, an Associate Fellow of The Royal Historical Society, and an undergraduate in English Literature, Film and History of Art at The University of Oxford.

Third fisherman: Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea.

Pericles, Act 2 Scene 1

First fisherman: Why, as men do a-land; the great ones eat up the little ones.

This conversation in Pericles between two fishermen guides the direction of the text towards a parable of the inherent struggle of human civilization: between the powerful and the powerless, the haves and the have nots, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, so on and so forth.

The maritime struggle between big and small fish symbolically tends to uphold the invasion of the Human-whales to the Anthropocene, gobbling up the small fish of our social and environmental world. The dissected, mutilated flesh of the small fish by the sharp teeth of the whale-agents of the socio-political, economic power hierarchy transcends the corporeality of dissected flesh to the realm of life-less repression of those human actors who live in the margins of the Anthropocene, and also different nonhuman environmental bodies of the social world.

The flesh of different small fish-human and environmental actors then get refurbished with the saliva of the dominant hegemonic culture, preparing the flesh to be digested in the oppressor's stomach. It produces and reinforces a certain degree of life-force to the whole body of the oppressor, and recalibrates the systematic civilizational wheel of suppression trans-spatiotemporally.

Sayan Parial is an Independent Scholar from Malda, India whose interests lie in Science Fiction, Partition Studies, Posthuman Studies, and Science and Technology Studies.

I am sick of this false world …

Timon of Athens, Act 4 Scene 3

Then, Timon, presently prepare thy grave:

Lie where the light foam of the sea may beat

Thy gravestone daily; make thine epitaph,

That death in me at others’ lives may laugh.

Act Four of Timon of Athens opens with its protagonist cursing the inhabitants of Athens as he departs the city to live as a recluse. Timon chooses a wood near the sea for his new home, though his self-imposed isolation does not grant him peace from humankind.

His caustic exchange with the cynic Apemantus later in this Act does, however, lead Timon to a pivotal insight. If he is so “miserable”, as Apemantus declares, then Timon “shouldst desire to die” (4.3.247). Timon considers the pertinence of this idea later in the scene.

Timon’s desire to commemorate his misanthropy is tinged with a sense of futility. Carving out an epitaph would indeed help him communicate his distaste for the world. His headstone would represent a place where he “may laugh” at the lives of others. This impulse is, nevertheless, undercut by the effect that the “light foam of the sea” would have upon this monument. The waves, beating his “gravestone daily”, would erase the very epitaph that carries Timon’s disdain for “all living men” (5.5.70).

Although he imagines that his grave will represent an “everlasting mansion / Upon the beached verse of the salt flood” (5.2.100–101), the enduring power of the sea seems set to wash away the detail from this site and, thus, erase any physical evidence of his life. Rather than being “everlasting”, Timon’s posthumous legacy is poised to be fleeting. “Neptune”, as the warrior Alcibiades remarks in the play’s conclusion, may “weep” in “memory hereafter” (5.5.76), but no human memorial can outlast the elements.

Dr Douglas Clark is a Senior Research Fellow in Early Modern English literature at the Université de Neuchâtel in Switzerland.

Edgar: Hark, do you hear the sea?

King Lear, Act 4 Scene 6

Gloucester: No, truly.

When Edgar asks his blinded father Gloucester in Act 4 of King Lear whether he can "hear the sea", Gloucester answers genuinely: "No, truly." As the audience, we know that there is no sea around.

At this part of the tragedy, all key players either move towards Dover (Edgar, Gloucester, the Fool, and Lear) or have crossed the English Channel (Cordelia). Yet a physical encounter with the sea does not occur. Edgar simply wants to save his suicidal father by making him believe that they are on the cliffs of Dover when they are not. No jump will hurt his father.

The emphasis on sound in Edgar's question underlines the tragedy's interest in appearance and the fickleness of human perception. The exchange also links the sea to the domain of the unknowable. As elsewhere in Shakespeare's plays, water is an unstable symbol in King Lear. Sea imagery hosts a variety of meanings. In the storm scenes Lear believes he is battling 'hurricanoes' (3.2.2), i.e. Caribbean windstorms, which adds to the play's notorious spatial uncertainty and signifies that Lear is transgressing the boundaries of his known terrain.

Cordelia calls her father "As mad as the vex'd sea" (4.2.2) and Lear talks about the "flight lay toward the raging sea" (3.4.13). In all these cases, the sea denotes a liminal space where reality meets the imagination. In this way, the sea becomes an allegory of the theatre itself. As the audience, we must suspend our beliefs in reality. To experience the magic of the theatre, we have to be able to hear the sound of the sea.

Kirsten Sandrock holds the Chair of English Literature and Cultural Studies at the University of Wuerzburg, Germany, and is especially interested in Shakespeare's Atlantic imagination.

See you now;

Your bait of falsehood takes this carp of truth:

And thus do we of wisdom and of reach,

With windlasses and with assays of bias,

By indirections find directions out:

So by my former lecture and advice,

Shall you my son.Hamlet, Act 2 Scene 1

Polonius claims to be an “assistant to the state” (2.2.167), but as we see in these instructions to Reynaldo, his statesmanship amounts to nothing more than manipulation.

Unconcerned with what is really true, Polonius’s “wisdom and reach” only uses lies and indirection to find out what others think. This brand of statesmanship is exactly like the inept seamanship of the one who calls himself “the true navigator” in Plato’s image of the ship of state in Republic (488c-489c).

Polonius is frequently associated with nautical imagery: “Yet here Laertes! Aboard, aboard, for shame!/ The wind sits in the shoulder of your sail,/And you are stayed for” (1.3.55). When he encounters Hamlet reading in the lobby he says “I’ll board him presently” (2.2.169). He speaks to Reynaldo of “finding/ By this encompassment and drift of question/That they do know my son” (2.1.9-11), and repeats the word “drift” shortly after (2.1.38).

The depiction of Polonius and Hamlet cloud-gazing (3.2.355-61), is a further reference to this trope that illustrates how thoroughly Polonius has misunderstood Hamlet’s “antic disposition”. Just as in Plato’s image of the ship of state, each thinks the other is a stargazer and mad fool. The word translated as “stargazer” is meteoposkopos (Republic, 489c); one who stares at the heavens or clouds. This scene concisely illustrates the disjunction between the perspective of the manipulative politician and that of the true statesman. Hamlet is the one who should rule, but the lying, fratricidal Claudius has stolen his rightful place, and enjoys Polonius’s full— if thoroughly inept— support.

Erich Freiberger teaches Philosophy and Public Policy at Jacksonville University and is writing a book on Shakespeare and Plato’s Political thought.

Main image courtesy of Dulwich College