2026 has a wide range of astronomical sights in store, including the UK's best solar eclipse since 1999, a lunar eclipse, a planetary parade, Jupiter and Saturn at their best, meteor showers, and much more.

Explore 2026's space and astronomy highlights with astronomers from the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

For more in-depth guides to the night sky each month, bookmark the monthly astronomy highlights blog or get yourself a copy of the 2026 guide to the night sky book.

Written by Jess Lee and Imo Bell.

January

1 - 12 January - See the Quadrantid meteor shower

2026 kicks off with the Quadrantids, one of the strongest and most reliable yearly meteor showers. Active from 28 December 2025 until 12 January 2026, this shower is famous for its 'fireballs', exceptionally bright meteors.

In 2026 the Quadrantid shower peaks in the early hours of 4 January, with a possible rate of up to 120 meteors per hour at the maximum. Unfortunately the Moon will be full on this night, so moonlight will drown out a lot of the meteors.

To see this shower, bundle up nice and warm, find a dark location free from light pollution, and fill your eyes with as much of the sky as possible. To work out if you’ve seen a Quadrantid meteor, trace it back to its radiant point, which should be in the northern part of the constellation Boötes.

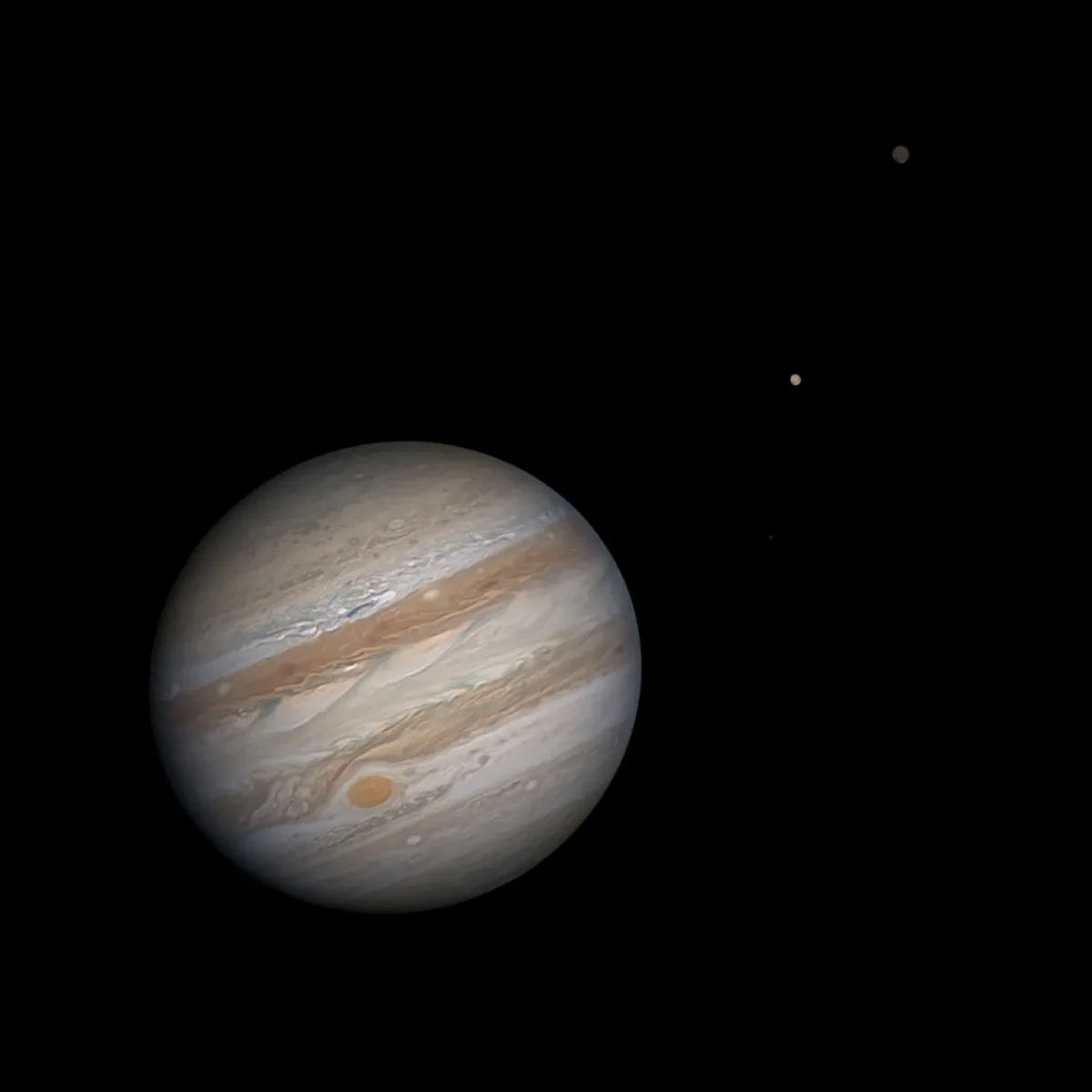

10 January - Jupiter at its brightest

When a planet is 'at opposition' it’s directly opposite the Sun in the sky, which fully illuminates the planet’s face and allows us to see it at its brightest.

On 10 January Jupiter will be at opposition, making this a great opportunity to set your eyes or telescopes on the beautiful gas giant. It will be visible in the sky all night, rising in the east around sunset and setting in the west around sunrise.

As it’s so bright, Jupiter will be easy to spot - even from a light-polluted area.

February

Search for another galaxy

February kicks off what is known as ‘galaxy season’ for the Northern Hemisphere, where we have the best opportunity to look at these stunning distant ‘cities’ of gases, dust and stars.

A new moon on 17 February gives you a chance to escape the light pollution of the Moon and get a good look at some galaxies.

An ever-popular astronomy and astrophotography target is the Andromeda Galaxy, one of our closest galactic neighbours at around 2.5 million light years away. You’ll find it near the Andromeda and Cassiopeia constellations.

For the best chance of observing the Andromeda Galaxy, get somewhere reasonably dark to look with a telescope, or especially dark to see it with a small pair of binoculars. Under very dark and clear skies, you can sometimes even make it out as a small smudge with the naked eye!

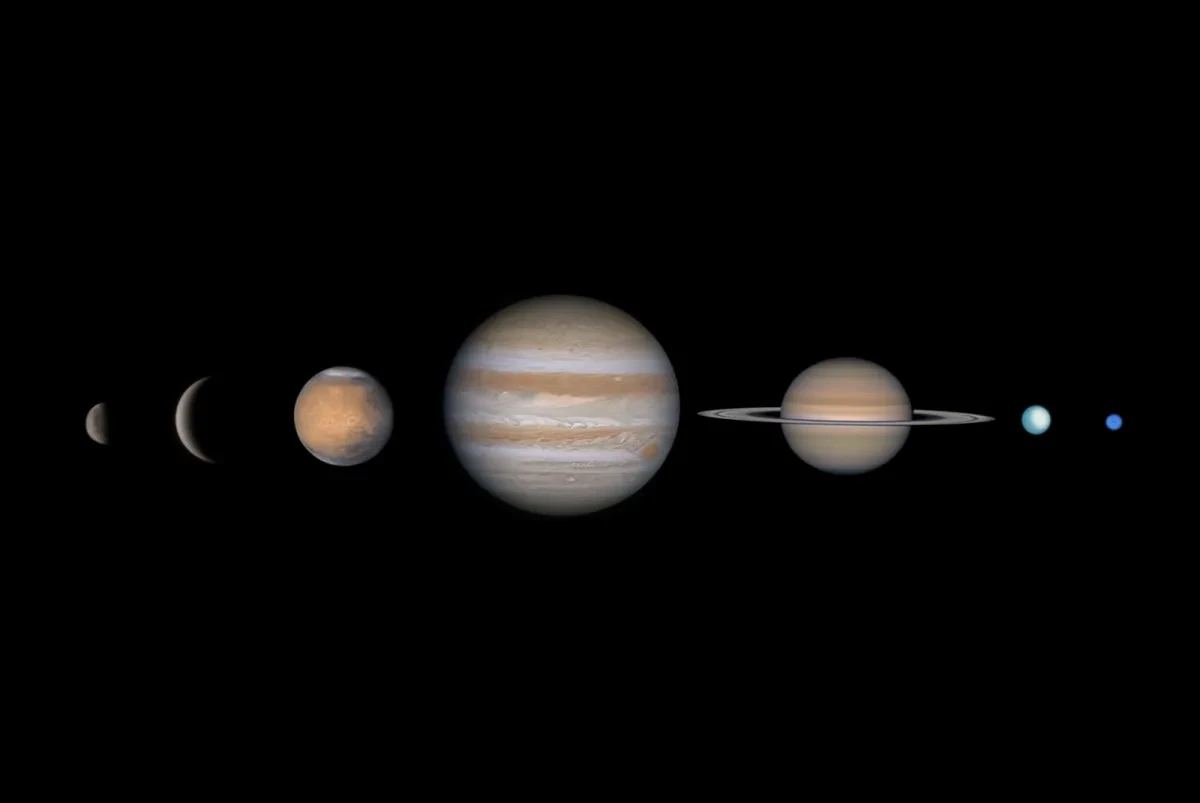

Late February – A parade of planets

At the end of February there will be six planets visible in the night sky, an event popularly known as a 'parade' of planets because they’ll all appear in a roughly straight line across the sky. As all the planets orbit the Sun at different rates, we see them in different positions in the night sky throughout the year.

On this occasion, Mercury, Venus, Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune will all technically be visible, but it’s definitely a challenge to see all six.

Mercury, Venus, Saturn and Neptune will be visible in the west very close to the horizon just after the Sun sets, making sunlight and anything on your skyline additional obstacles to spotting these planets. Neptune will also, as always, require a telescope to see.

Uranus is higher in the sky in the constellation of Taurus and will set around midnight, so you’ve got a better chance of finding the planet if you have a telescope.

Jupiter will be high in the sky for most of the night in the constellation of Gemini and will be the easiest of the six to find. It will be a bright point of light visible to the naked eye, even from a light-polluted area.

19 February - Mercury at greatest elongation

Mercury will reach its greatest elongation east, its farthest point from the Sun, for the first time in 2026 on 19 February. As it’s an eastern elongation this will be seen in the evening.

Its greatest elongation east will happen again on 15 June and 12 October, and it will reach its greatest elongation west (best seen in the morning) on 3 April, 2 August and 20 November.

As with any observation close to the Sun, make sure you don’t look directly at the Sun and, if observing with a telescope or pair of binoculars, wait until after sunset or before sunrise to avoid accidentally pointing your equipment at it.

March

20 March – The vernal (spring) equinox

Changes in the length of day and night are caused by the tilt of the Earth. When Earth orbits the Sun, at certain times of the year the Northern Hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun and the Southern Hemisphere is tilted away from it. For the other half of the year, the reverse happens.

Equinoxes happen when neither hemisphere is tilted towards or away from the Sun and there are roughly equal hours of daylight and darkness. Solstices, on the other hand, happen when a specific hemisphere is tilted towards or away from the Sun, which results in long days or long nights.

The spring equinox will occur on 20 March in the Northern Hemisphere, and this is when astronomical spring is said to start.

April

April - See Artemis 2 launch

In December 2022, the Artemis 1 uncrewed test mission splashed down on Earth after successfully completing an epic journey to and around the Moon, where it made two lunar flybys and entered into lunar orbit.

Scheduled for launch in April 2026 (exact date to be confirmed), Artemis 2 is the next step in the ambitious Artemis programme, which aims to put humans back on the Moon, build a space station in lunar orbit, and lay the groundwork for sending humans to Mars.

Artemis 2 won’t put humans back on the Moon just yet – instead, the mission will involve a crewed flight just beyond the Moon which will take humans the farthest they’ve ever been in space. Forming the crew are decorated astronauts Christina Koch, Victor Glover, Jeremy Hansen and Reid Wiseman.

After being launched on the Space Launch System rocket, the crew will fly the Orion module 8889 km beyond the Moon, complete a lunar flyby and return to Earth.

Lasting between eight and ten days, the mission aims to gather valuable data on the Orion module, including how effective its life support systems are.

16 - 25 April - Look out for the Lyrid meteor shower

In 2026 the Lyrid meteor shower will be visible from 16-25 April, peaking on 22 April.

Although it's far from one of the most active yearly meteor showers, the Lyrids can still dazzle - some meteors have bright dust trails that glow in the sky for several seconds.

What’s more, at the shower's peak on the night of 22 and morning of 23 April the Moon will be just before its first quarter phase, so won't cause too much light pollution.

The Lyrids originate from Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, which does a lap of the Sun once every 415 years. It’s the oldest recorded meteor shower still visible today, having first been recorded in 687 BCE.

May

31 May – Blue moon

Fans of gazing at the Moon are in for a treat in May 2026 - there will be two full moons, one on 1 May and the second on 31 May.

As the second full moon in a month, the one on 31 May is a ‘blue moon’ according to one of the two definitions of a blue moon.

Sadly, the Moon won’t actually turn blue, it’s just a name!

June

8 June – Venus and Jupiter conjunction

While Jupiter and Venus are both fantastic sights independently, they’re going to be even more impressive side by side in the evening sky. This conjunction (or close approach) of the two planets will be visible in the southwest from sunset until they disappear below the horizon at around 11pm, assuming you have an unobstructed view in this direction.

If your horizon is clear and the weather is good they won’t be hard to spot, as both planets will be very bright points of light. They'll be approximately one finger width apart and just below the stars Castor and Pollux in the constellation of Gemini.

21 June – The summer solstice

The Northern Hemisphere will mark the summer solstice on 21 June, the 'longest day of the year', when there will be around 16.5 hours of daylight.

The exact time of the solstice is at 9.24am BST, and that is the moment when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted farthest towards the Sun. From here onwards the days will get progressively shorter until the winter solstice on 21 December.

July and August

17 July – 24 August - The Perseid meteor shower

In July and August the Perseid meteor shower will take place, caused by the debris stream from the comet Swift-Tuttle.

The Perseids are a highlight of many astronomers’ calendars due to their high hourly rate and bright meteors. At the peak you could see up to 150 meteors per hour, and you might even catch some fireballs too.

In 2026 the Perseid meteor shower is active between 17 July and 24 August, with the shower peaking on 13 August. Fortunately, this year the peak of the shower occurs during new moon, so conditions are ideal for seeing the best of the Perseids – moonlight won’t drown out the fainter meteors.

Meteors will appear to radiate from the constellation of Perseus, so find a dark spot and look there for the best chance of seeing some shooting stars.

12 August – Partial solar eclipse from the UK

At long last the UK is being treated to an almost total solar eclipse, and as the best solar eclipse seen in the UK since 1999, this truly is an event to clear the diary for.

Viewers in London will see the Moon touch the edge of the disc of the Sun at 6.17pm BST. The Moon will gradually cover more of the Sun until the maximum at 7.13pm, and finally leave the disc of the Sun at 8.06pm.

At the eclipse's maximum, 90% of the Sun will be covered by the Moon, which is enough to notice a difference in the weather and light levels.

Only the lucky handful of countries that fall within the path of the eclipse will be able to see it, as the Moon only casts a small shadow on the Earth when it moves between the Earth and Sun. Viewers in some parts of Iceland and Spain will be able to witness the first total solar eclipse in Europe since 1999!

Don’t go into this much-anticipated event unprepared. As you must never look directly at the Sun to protect your eyesight (even during an eclipse), make sure you have a pair of eclipse glasses, access to a solar telescope (check out your local astronomical society) or that you use a pinhole projector.

Here at the Royal Observatory we’ll be live streaming the eclipse - stay tuned for more details!

15 August – Venus at greatest elongation east

Venus and Mercury are bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye, but because they're closer to the Sun than Earth is, they rarely get far from it in the sky. This makes them difficult or even dangerous to see at times. This is especially true for Mercury, which is smaller, fainter and closer to the Sun than Venus.

If you’d like to see these rocky worlds for yourself, your best bet is usually to wait for their greatest elongation. This is the time when each planet is farthest from the Sun, and therefore more likely to still be above the horizon when the blinding Sun has set.

Venus will reach its greatest elongation east (and therefore seen in the evening) on 15 August, and its greatest elongation west (seen in the morning) on 3 January 2027.

28 August – Partial lunar eclipse from the UK

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon moves into the Earth’s shadow, either fully or partially.

This partial lunar eclipse in the UK will begin at 3.33am BST. The Moon will move further into Earth's shadow until the maximum of the eclipse at 5.12am, when approximately 90% of the Moon will be in Earth's umbra, the darkest part of its shadow.

After this, the Moon will slowly move out of umbra until the Moon sets and the eclipse is no longer visible - around 6.15am. The Moon will be increasingly low on the horizon as the eclipse progresses, so you'll need to find a high point with a clear view to the southwest to see the best of this event.

Never miss a shooting star

Sign up to the Royal Observatory's space newsletter for exclusive astronomy highlights, night sky guides and out-of-this-world events.

September

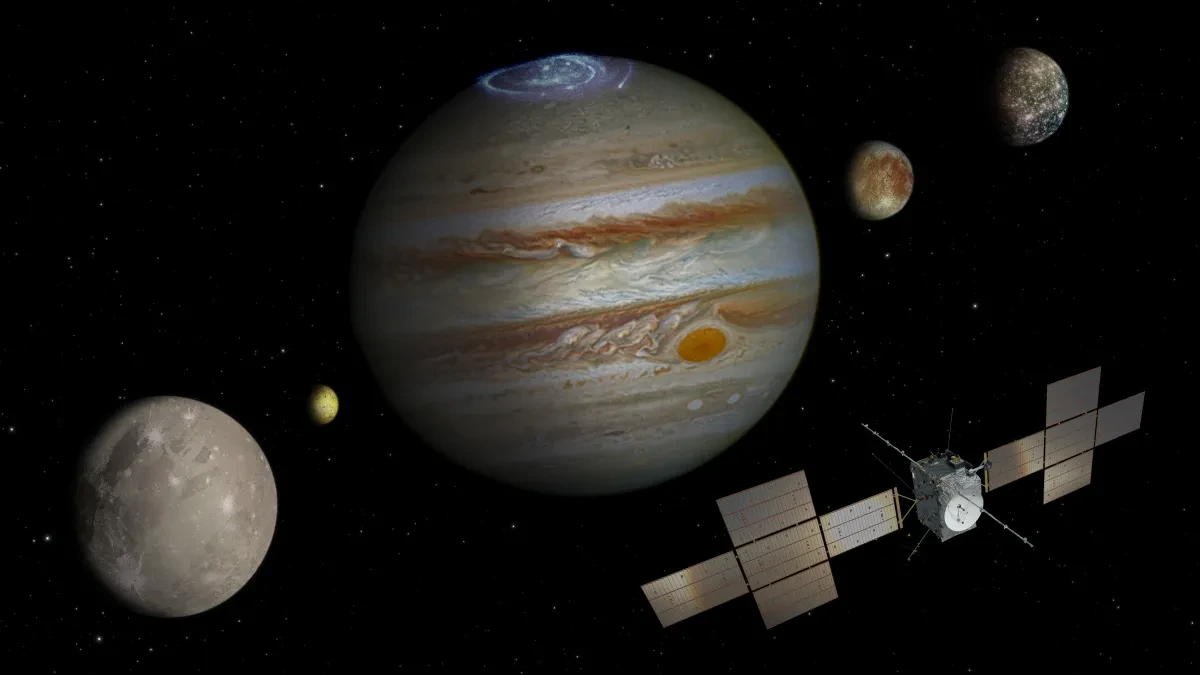

September – JUICE makes a gravity-assisted boost

On 14 April 2023, JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) began its intrepid voyage towards Jupiter, a mission that intends to uncover any secrets hiding beneath the surfaces of three of Jupiter’s Moons - Ganymede, Europa and Callisto.

However, JUICE isn’t able to zip straight over to the Jovian system, and will need to swing by the Earth and Venus to get a boost from their gravity. The first of two Earth flybys by JUICE will take place in September 2026, with JUICE coming within 9,000 km of our planet.

23 September - Autumnal equinox

In 2026 the autumnal equinox will occur on 23 September at 1.06am BST. On this day the Sun will illuminate the northern and southern hemispheres equally, and day and night will be roughly the same length.

The full Moon closest to the autumnal equinox, which usually falls in September, is popularly called the Harvest Moon. It is thought that this name was used by historic Europeans because the light of the Moon helped farmers work late into the night harvesting crops. In 2026 the Harvest Moon will be on the night of 26 September.

October

2 October – 7 November - The Orionid meteor shower

With a maximum rate of around 15 meteors per hour, the Orionid meteor shower is active from 2 October until 7 November and peaks with a broad maximum lasting about a week around 21 October.

In 2026 the Moon will be in its waxing gibbous phase during the peak, so moonlight will unfortunately interfere with seeing the best of this shower, but its long duration means you’ll have other chances to see Orionid meteors.

Orionid meteors tend to be particularly fast with persistent trains, and they originate from Comet 1P/Halley, famously known as Halley's Comet.

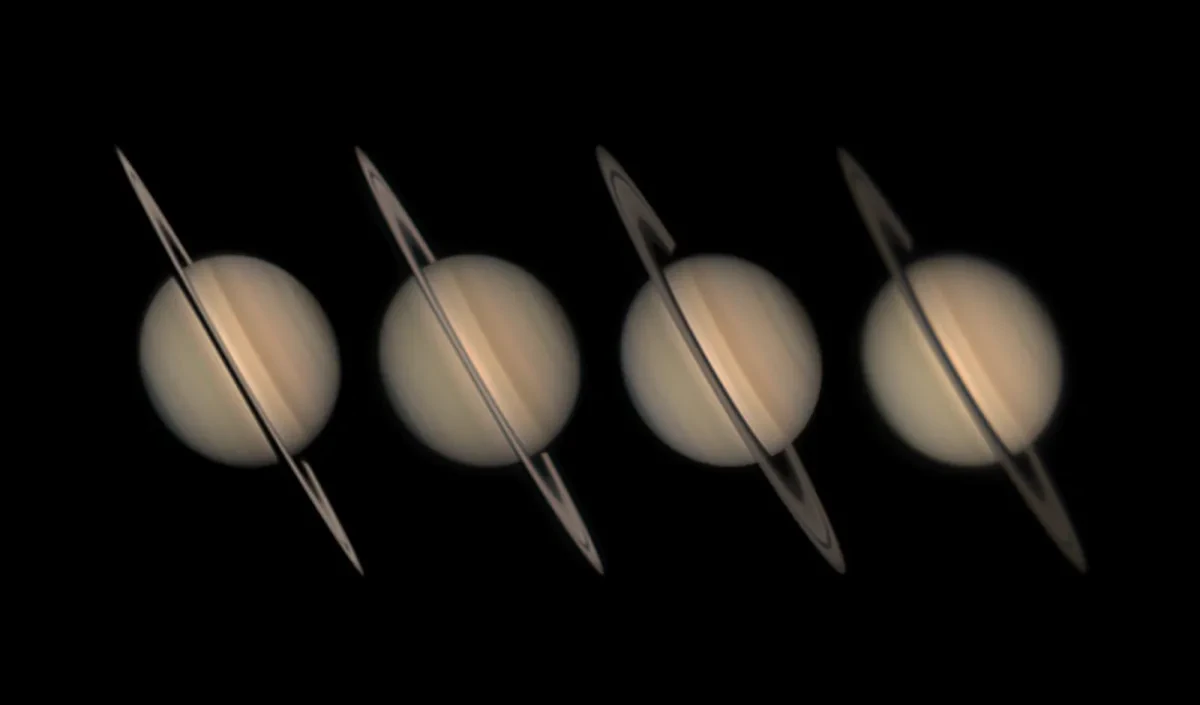

4 October – See Saturn at its best

Saturn reaches opposition on 4 October, meaning it’ll be directly opposite the Sun in the sky and therefore look especially bright to us.

As one of the more visible planets to reach opposition, this could be a good opportunity to try to capture some photos of the beautiful ringed planet.

Around this date, Saturn will rise in the east around sunset and set in the west around sunrise, meaning it’s visible in the southern sky all night long.

November

The Pleiades, the ‘Seven Sisters’

November is a great time to observe the Pleiades star cluster, one of the most easily recognisable asterisms (pattern of stars) to spot in the night sky during the winter.

This open star cluster sits within the constellation of Taurus the Bull and is visible with the naked eye. While you may assume there are only seven stars in the cluster, there are actually over 1,000, but only six are usually visible with the naked eye. Stargazers with sharper eyes, however, may be able to spot more members of the family.

No viewing equipment is needed to see the sisters, but taking a look with binoculars or a telescope will allow you to look closely at individual gems within the cluster.

December

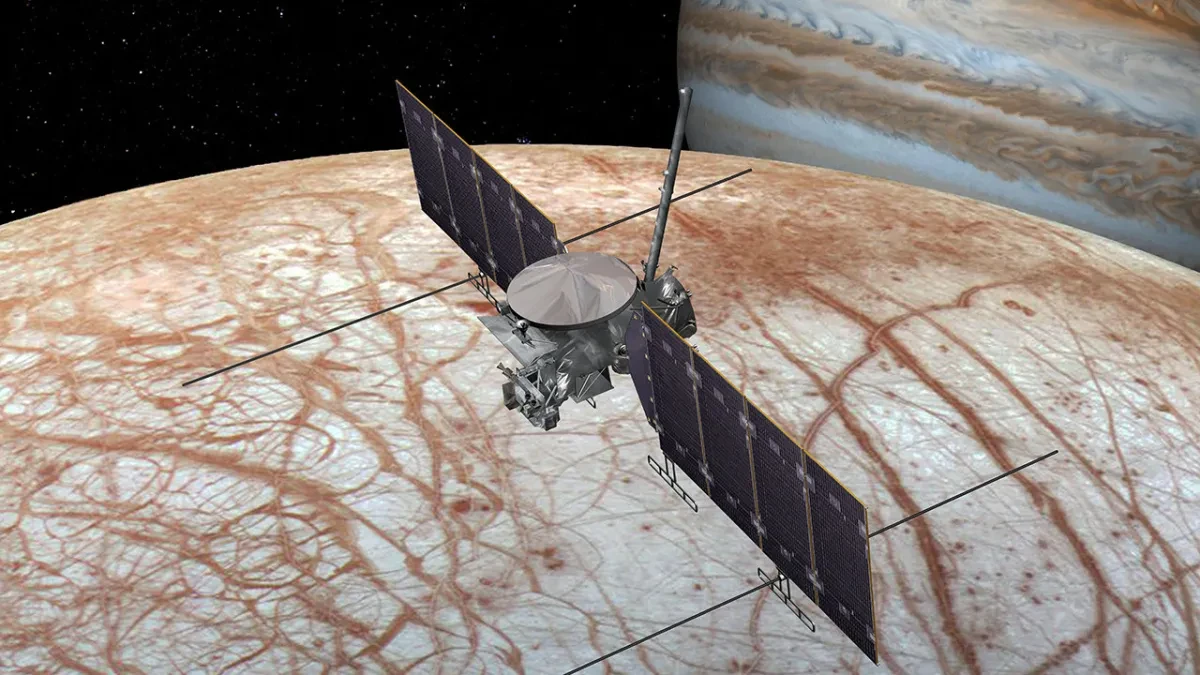

3 December - Europa Clipper makes a gravity-assisted boost

The Europa Clipper has been on its way to Jupiter since October 2024, when it launched from the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida. However, just like the JUICE spacecraft, it isn’t travelling straight there.

Both spacecraft are taking journeys that loop them around the Sun and past other planets for ‘gravity assists’ before finally arriving at the Solar System’s largest planet.

The Europa Clipper will return close to Earth on 3 December, passing around 3,200 km above the surface before continuing on to Jupiter.

4 - 20 December - Spot the Geminid meteor shower

The Geminid meteor shower, with a possible rate of 120 meteors per hour at the peak, is usually one of the best meteor shower displays you can see all year. This wintry shower makes the long hours of December darkness a little more enjoyable.

In 2026 the Geminids will be active between 4 and 20 December. The shower reaches its maximum on 14 December, when the Moon will be a waxing crescent and set at around 9pm, so lunar light pollution luckily won’t interfere with seeing the peak.

Geminid meteors are often slower than those from most other meteor showers, and so they can appear to last longer.

Fill your view with the sky and wait for the lights to appear. And, given this is a midwinter wonder, don’t forget to wrap up warm!

21 December - The winter solstice

The winter solstice, the point at which the Northern Hemisphere will be tilted farthest away from the Sun, will occur on 21 December.

On this day there will be slightly less than eight hours of daylight in London. Whilst many people celebrate the whole day, the exact moment of the solstice will occur at 8.50pm.

24 December - Marvel at a supermoon

Have you ever looked up at the Moon and thought it looked particularly big and bright? Your eyes probably weren’t deceiving you; sometimes the Moon is closer to us in its elliptical orbit, making it look especially large.

The Moon's closest approach to us is called perigee, and when a full moon happens very close to perigee we call it a supermoon. At this time, the full Moon will appear up to 14% bigger and 30% brighter than when it’s farthest away (apogee). There will be one supermoon in 2026, right at the end of the year on 24 December.

2026 guide to the night sky

What’s on

See events at the Royal Observatory.

Header image: Navigating Through the Deep Blue © João Yordanov Serralheiro, shortlisted in ZWO Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2025