The six-pip time signal was introduced on 5 February 1924. During 66 years of collaboration between the BBC and the Royal Observatory Greenwich, the major global news headlines of the day were preceded by the six Greenwich time 'pips'.

When the BBC broadcast the news of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon, President Kennedy’s assassination, and the destruction of the Berlin Wall, the reports followed the familiar sound of the Greenwich pips.

What’s the time? The need for standardised time

When you need to know the time, what do you do? Do you check your smartphone or smartwatch? Ask someone nearby? You might look at your oven clock, your car clock, or the time displayed on your computer. You could even google ‘what’s the time’! It is fair to say that today we are surrounded by accurate time.

One hundred years ago, many of these things did not exist and public clocks in towns and cities could all show different times. Around 1908, several articles appeared in the newspapers where writers complained about ‘lying clocks’, as too many clocks showed different times and it was hard to know which one was right.

London was seen to be the worst offender. Back then, astronomers at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich determined Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), which had been legal time in Britain since 1880. They had a system of electric clocks, where each clock connected by wires showed the same time. These wires extended beyond the Observatory and shared time signals with the railways and post offices, who needed accurate time for their timetables and scheduling.

Companies needing accurate time subscribed to the General Post Office (GPO), who for a fee distributed the Greenwich Time Signal. Other businesses and municipalities also relied on ‘synchronised systems’ in which all their clocks ran at the same time.

A well-known supplier of electric clocks was the Synchronome company, led by electrical expert Frank Hope-Jones who played an important role in the history of the six pips. Many businesses got their time from the Standard Time Company, who subscribed to the GPO service and then sold it on through their own networks.

But this did not guarantee it was the right time, as errors could creep in along the way. Only those with a direct line to the Observatory could claim to show accurate Greenwich time.

The BBC and the Royal Observatory team up

In 1924 Lord John Reith, director of the newly formed BBC, felt the company should supply the public with an accurate time signal. Initially, in 1922 the BBC replicated the chimes of Big Ben on tubular bells to signal the time. Later it received an hourly signal from the Standard Time Company.

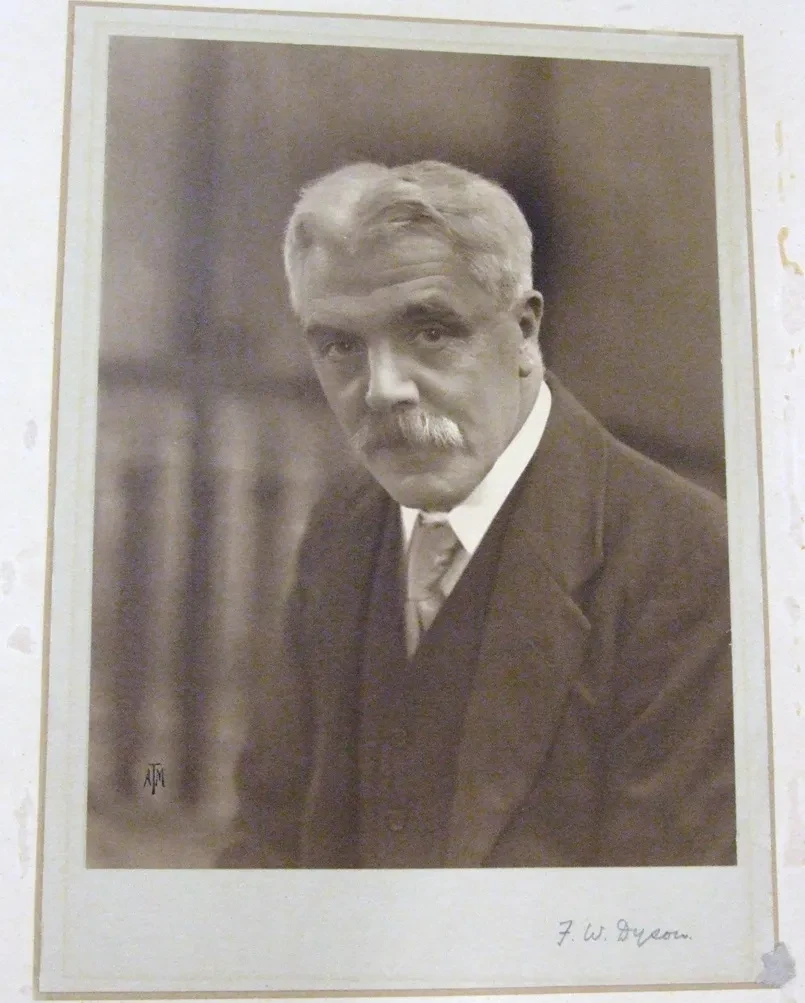

But, following a suggestion by Frank Hope-Jones, John Reith thought the public deserved the best time signal available: one that came directly from the Royal Observatory. The BBC approached Astronomer Royal Frank Dyson, who agreed to connect an accurate clock at the Observatory with the BBC.

The observatory fitted out one of their regulators, known as 'Dent 2016' (pictured above), with control switches that sent a time signal to the BBC every 30 minutes. By this time, the regulator was already 50 years old with an impressive career.

'Dent 2016' had been to New Zealand in 1874 for the Transit of Venus, and in 1882 travelled to Barbados for the same purpose. In 1892 it spent time in Waterville, Ireland, to help measure the longitude. After that, the regulator was used at the Observatory for another 30 years before it became the six-pip clock.

The firm Dent were well-known for helping the public get accurate time. They made the clock for Big Ben, whose ‘gong’ was initially used by the BBC, and some years earlier, a clock for the Royal Exchange. A year after the Observatory adopted 'Dent 2016' for the pips, they upgraded another clock, 'Dent 2012', as a backup.

The first broadcast of the BBC pips

Timed by 'Dent 2016', the six pips were first broadcast live from the BBC on Tuesday 5 February 1924 at 9.30pm, with special guest Frank Dyson, Astronomer Royal at the Royal Observatory.

Earlier, in 1923, Frank Hope-Jones had helped listeners get ready for daylight saving time by counting down the last five seconds of the hour just before 10pm, instructing them to adjust their clocks at the last second to 11pm – British Summer Time. It was this countdown that Frank Dyson replicated with an additional sixth pip.

The live broadcast lasted 15 minutes, with Dyson delighting listeners with a history of the Royal Observatory before counting ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6’, with ‘6’ indicating the exact hour.

Initially the pips were not known as the pips: for the first several years newspapers called them the ‘ticks’ or ‘dots’.

Then in 1929, one newspaper referred to them as the six pips. During a broadcast to celebrate the move to the new Broadcasting House on Savoy Hill, Frank Hope-Jones counted down the hour again, but this time repeating the word ‘pip’. The name has stuck ever since.

The end of the BBC pips from Greenwich

By the 1960s timekeeping technologies were rapidly developing.

In the 66 years of collaboration between Royal Observatory Greenwich and the BBC, timekeeping moved from relying on the most accurate pendulum clocks through quartz technology to atomic timekeeping. Leap seconds were introduced, and time was redefined.

In 1972, almost 50 years after the first BBC pips, a major change occurred that not everyone would have noticed. On 1 January listeners no longer received GMT when listening to the six pips. Instead, listeners tuned into Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which was introduced at midnight.

The UTC system was a new timescale based on the Earth’s rotation and International Atomic Time. It was far more precise than GMT. Time was no longer determined by astronomers looking at the stars with clocks and telescopes.

By the 1990s this technology had developed even further, and it was possible for the BBC to buy its own equipment to supply accurate time signals. The Royal Observatory was also downsizing, and during its move to Cambridge in 1990 the time department was disbanded.

The last six pips were transmitted from the Royal Observatory on 5 February 1990, on the 66th anniversary of the pips. The BBC marked the occasion by offering the Royal Observatory a presentation microphone.

But this was not the end for the Dent clocks: they are now cherished objects in the Royal Museums Greenwich collections and if you’d like to see them and learn more, do visit the Royal Observatory in Greenwich where 'Dent 2016' is proudly on display.

Dr Emily Akkermans is Curator of Time at the Royal Observatory