I couldn't wait to explore the ship model collection as part of my Museum Fellowship.

Before I even made the trip to Chatham Docks I was going through the collection online, browsing the images and seeing what caught my eye.

The evidence of craftsmanship was astoundingly evident, and the attention to detail resonated with me. I went through the entire catalogue noting the ones I wanted to see on my visit. I was also made aware of the ‘World Cultures Ship Model Collection’ (previously known as the ‘Ethnographic Collection’…).

I wanted to find out what materials and making methodologies were utilised by model makers in other parts of the non-Western world, and what purpose they served. In comparison to the ship models that were made as private commissions, the ship models in the World Culture collection appear to be made for tourists, but they also denoted superb craftsmanship, utilising plant and animal material.

I was also intrigued to see whether I could find any female ship model makers. Timehri – my own ship model that led to this Fellowship in the first place – is a storyteller, and an integral part of her journey is about being 'visible': taking up space and narrating her story through reclamation of her identity. Were there any other pieces in the collection like her?

I went through the ship model records online again with a fine-tooth comb, but many simply stated the makers as ‘Artist unknown’.

Then, finally, I found one that didn't.

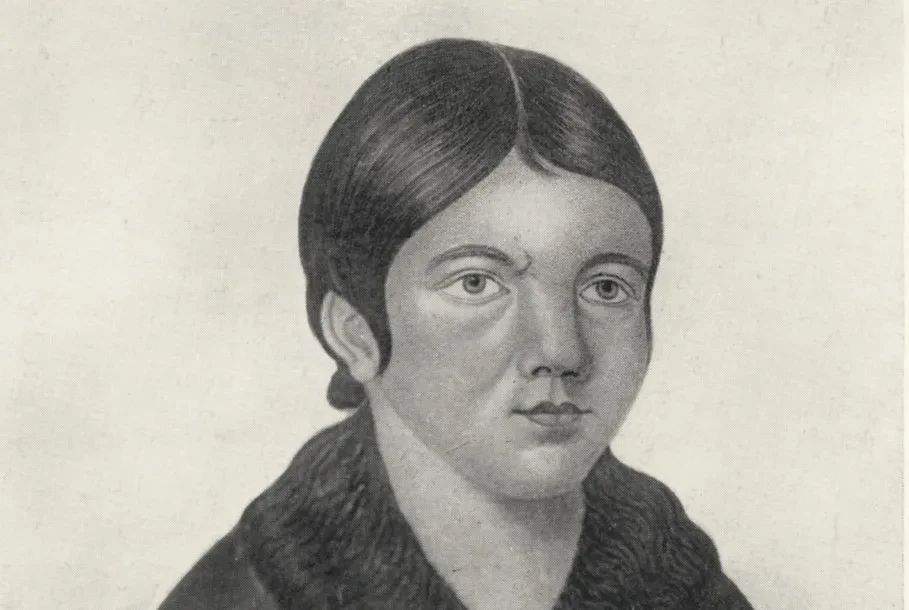

Shanawdithit: the female model maker

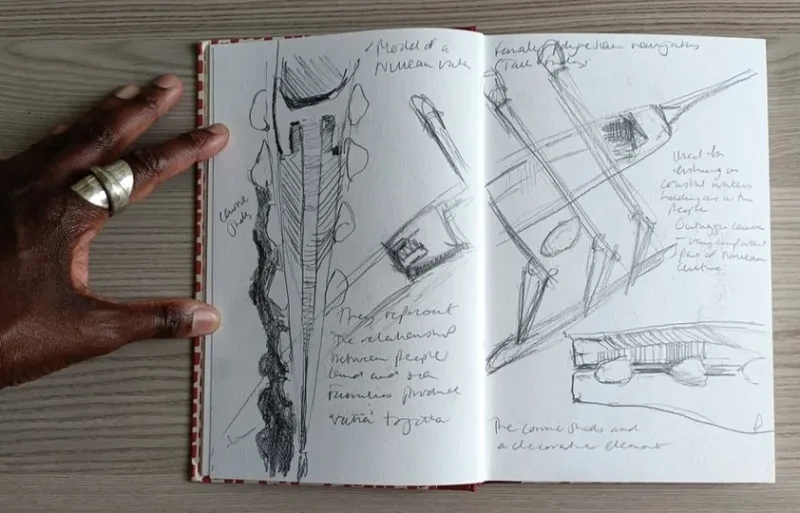

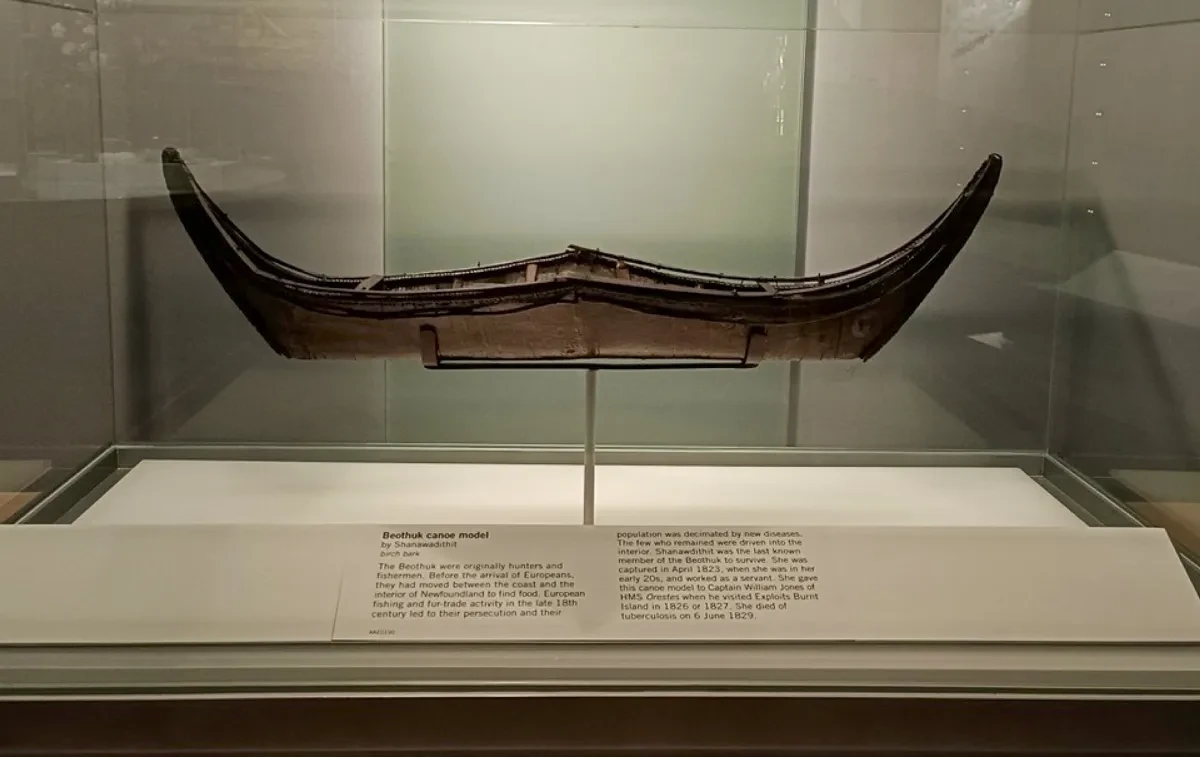

I came across a model with the creator's name listed as ‘Nancy Shanawdithit’. The description stated that the model was 'of a Beothuk or "Red Paint People" birch bark canoe (circa 1826), from Newfoundland, Canada'.

Intrigued by Shanawdithit (also noted as Shawnadithit, Shawnawdithit, Nance, Nancy or Nancy April) I started to uncover her story, and further discovered that she was also a mapmaker and draughtswoman too.

Shanawdithit was born at Red Paint Lake, Newfoundland in 1801. Many Beothuk people perished in battles against European colonisers, whilst other Indigenous peoples succumbed to tuberculosis. In 1823 her mother (Doodebewshet) and her sister were captured by English fur traders and taken to St John’s.

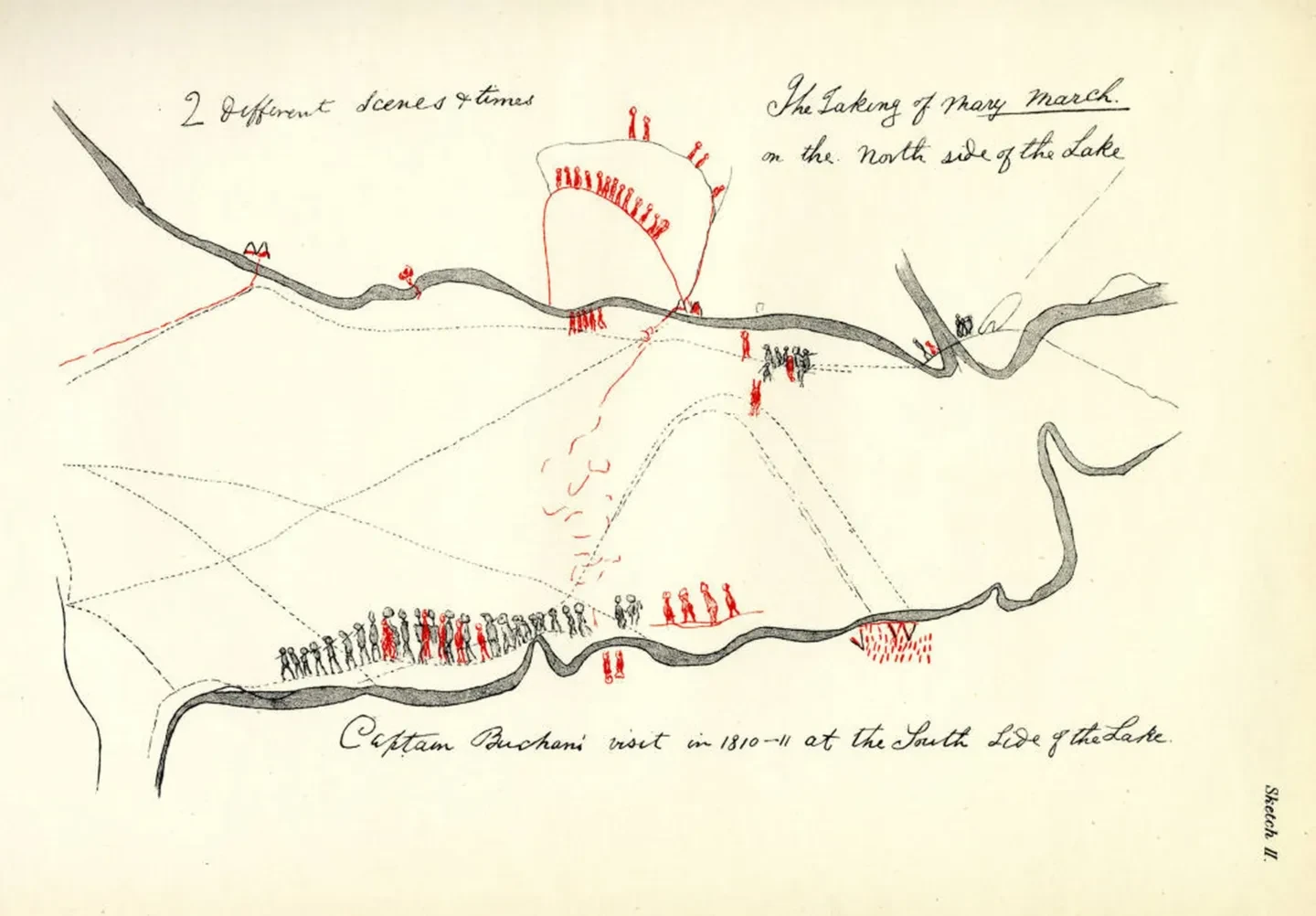

Shanawdithit worked as a domestic for Sir John Peyton. Later on, she was commissioned by the scholar William E Cormack to create drawings for the Beothuk Institution, depicting the history, cultural customs and way of life – such as religious rituals, living quarters and diet – of her nearly extinct people.

She also captured through her drawing a brutal encounter between her village and a convoy of English troops, and another occasion when Beothuk women were murdered in 1828. According to my research, she was one of the last of the Beothuk people to have interacted with the Europeans later in life.

In 1829 Shanawdithit passed away from tuberculosis. In 2000 she was recognised as a National Historic Person in Canada. Without Shanawdithit's accounts of her nation’s life, the Beothuk voices would nearly be absent from historical record.

Her craftswomanship was absolutely exquisite and I found her vessel in the Atlantic Worlds gallery at the National Maritime Museum. This was both a pleasant surprise and truly a unique experience meeting her model vessel face to face. There is absolutely nothing compared to seeing artefacts in the flesh as opposed to through a digital interface; it’s a totally different experience.

Beothuk Birch Bark canoe model

On display in the Atlantic Worlds gallery at the National Maritime Museum.

'William Brown' – the first black woman in the Royal Navy

Having discovered Shanawdithit, I continued to research women at sea with a focus on black and indigenous women.

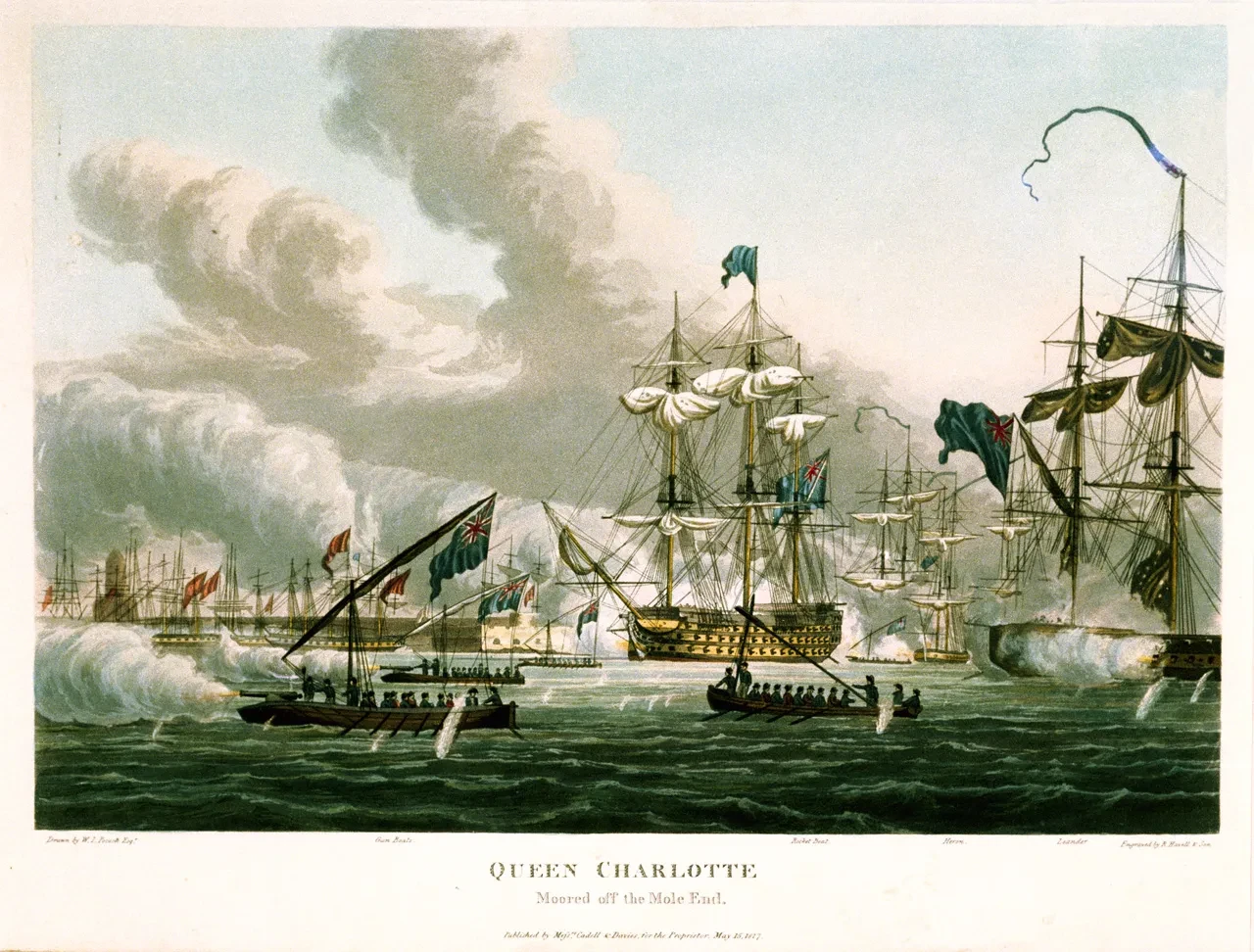

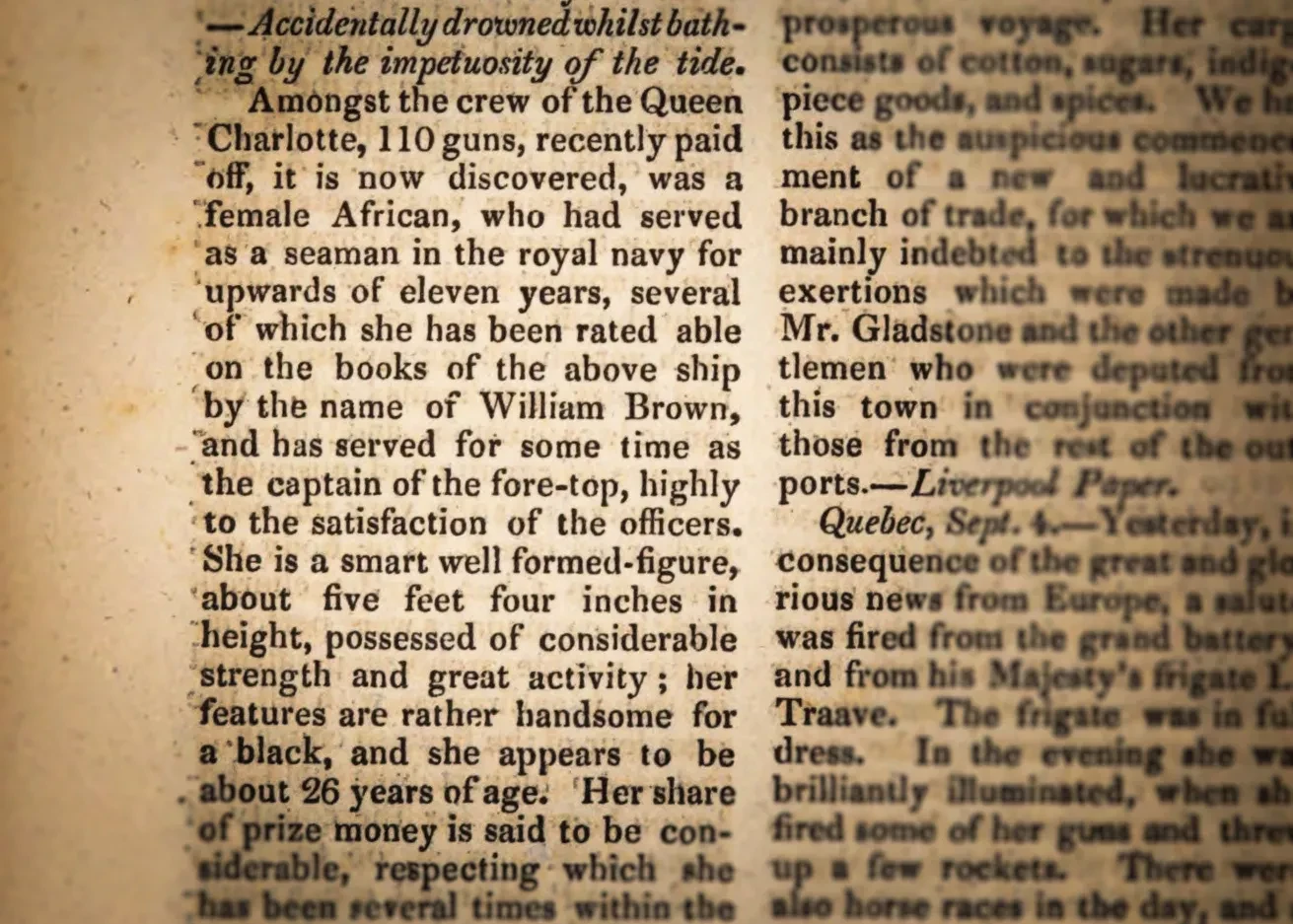

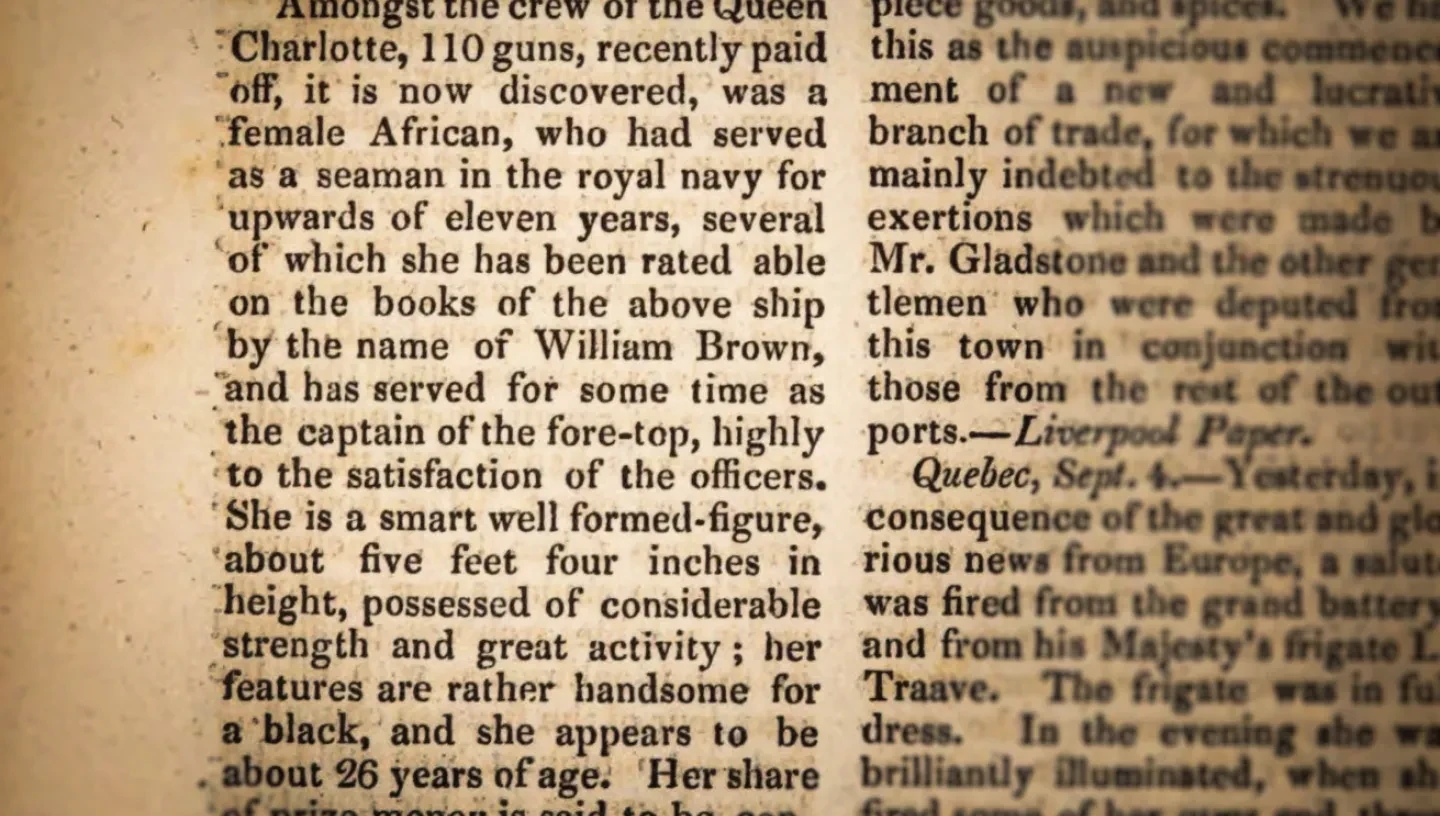

I was curious to see if there were any black female sailors and started to investigate. I discovered 'William Brown', who was female and disguised herself as a man (real name unknown) from Grenada, West Indies. She was the first black woman to be in the British Royal Navy on board the Queen Charlotte in 1815. She was subsequently dismissed upon being discovered as a woman.

However, there are a few varying accounts and conflicting reports on her service. The muster list for this ship states that the 21-year-old William Brown joined the crew on 23 May 1815 and discharged on 19 June the same year. The Annual Register of 1815 however described William Brown as ‘a female African, who had served as a seaman in the royal navy for upwards of eleven years’.

The Times report printed 2 September 1815 stated: ‘She is a married woman; and went to sea in consequence of a quarrel with her husband, who, it is said, has entered a caveat against her to receiving her prize money.’ I also discovered a potential plaque to commemorate her achievement which has yet to be fully realised, but I will be keeping my ears to the ground!

Having had conversations with key curators about women at sea, it was mentioned that women also kept their households in order on the domestic front for their families, raising children whilst the men were at sea. They are not listed or recorded, but played an important role nonetheless.

Penelope Steel: London's 19th century mapmaker

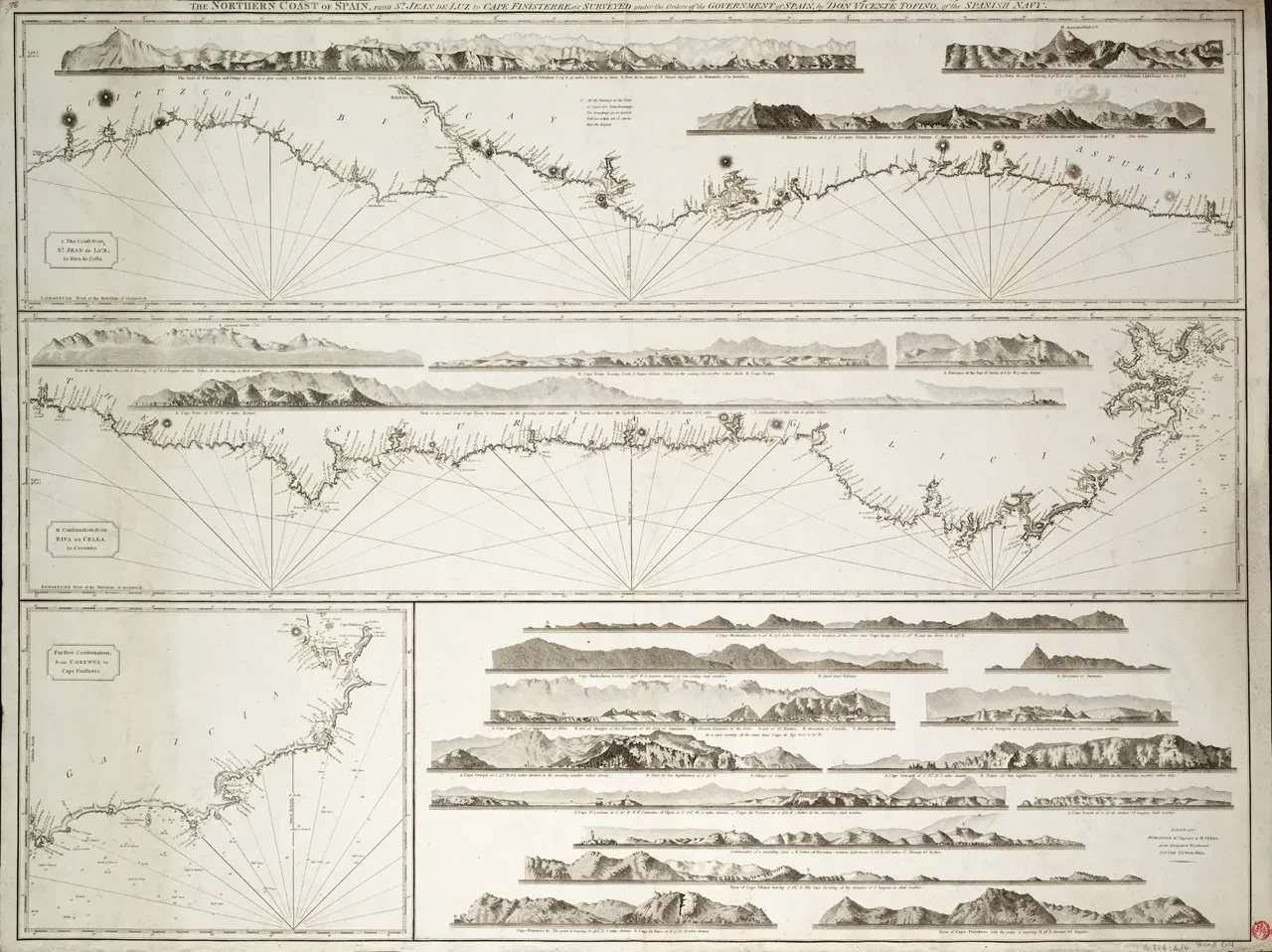

Each new discovery started with a question, curiosity and an open mind. My quiet obsession with maps had an opportunity to be channelled through my question: Were there any black and/or indigenous women map makers or nautical chart makers in the collection? Let’s see and find out...

Whilst delving deep into the collections I discovered the mapmaker Penelope Steel – I recall it was very late in the evening at the time! I immediately wanted to follow this new branch of research, and find out more about Penelope's complex, intriguing life story.

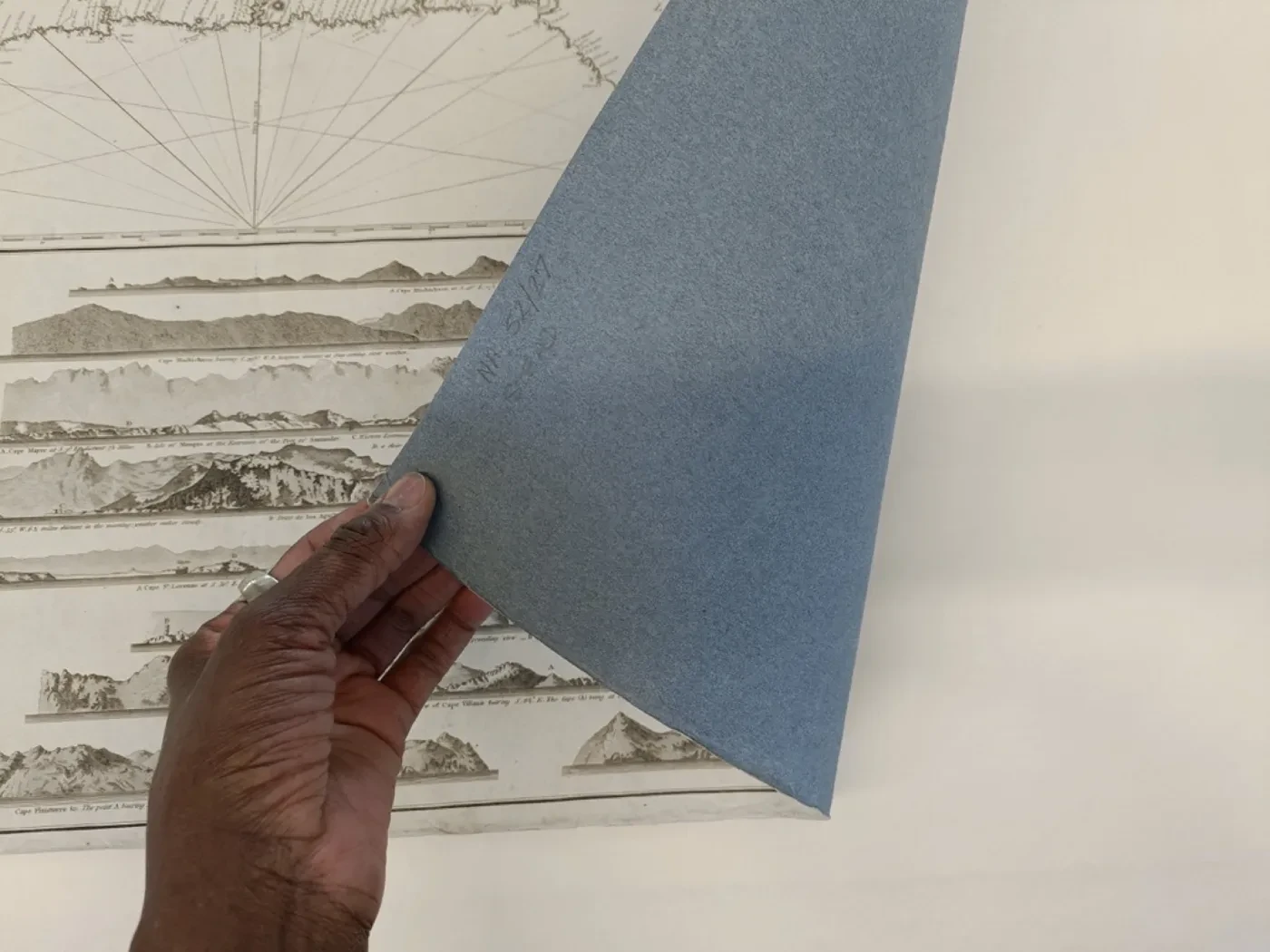

I arranged to view some of her maps at the Caird Library. Online catalogues are great, but you cannot beat the experience of handling these kind of items in person. I looked at her map of the River Thames, a blue-backed example and a linen-backed one. This really was a moment: holding a map made in 1804. As a walker, I could identify locations familiar to me, but also imagine Penelope herself exploring the foreshore on a walk. I also started to think about her life as a mixed race woman in a predominantly male working environment.

Threading the stories together

I fully embraced an opportunity to curate my own one woman show at a gallery called ‘Making Space’ in Aberfeldy Village.

I wanted to create a ‘living map’ installation: experiential exhibition that brought the different threads and narratives together, including both works from my riverwalking practice and my journeys during the Creative Research Fellowship.

On reflection the term Rhumblines was born out of this ongoing journey and process: a creative, metaphorical narrative device that threads complex river-related stories together. This was also the title of my exhibition and the continuation my project work around the river currently.

I prepared the space, created a pop-up shop selling handmade artefacts, organised a Private View and hosted many guests including curators from Royal Museums Greenwich. I also designed conversational workshops, connecting with a diverse range of visitors from local businesses and community members. My door was open!

The journey continues

There is much more to be revealed through the commissioned piece I have recently created, which is now on display in the Queen’s House. The Rhumblineage of Penelope Steel is inspired by Penelope's life, and is a collaged narrative that explores some of the complex knotted threads within herstory. Learn more about the artwork here.