My Creative Research Fellowship aimed to explore the collections from new perspectives and to engage with audiences in different ways.

The project would also provide new inspirations, insights and ideas to feed into my own practice and personal development. However, I did not have a clearly defined project title. I had to trust Timehri’s navigational instinct and keep an open mind.

Timehri, as I covered in the first instalment of this blog series, was my starting point, my main navigator leading the way on this journey as ‘sojourner’. She is much more than a ship model, and reconstructing her was a very intuitive process. She encapsulates and embodies aspects of my ancestral heritage, creativity, values and artistry. Her creation is symbolic of an ongoing voyage of self-discovery, rediscovery, excavation, identity, re-memory and repair – to name but a few.

In a much wider context, this voyage of Timehri is also, on reflection, an ongoing journey from ‘enslavement to emancipation’ from an artistic, personal and socially engaged perspective. I recognised that this was analogous to the transatlantic slave triangle but in reverse: reconnecting to the Motherland…

With all that in mind, what might the next steps of my Fellowship be? Where was I going to start? It felt akin to exploring a vast ocean of treasures, which was overwhelming and exciting at the same time.

I think of the National Maritime Museum as a ‘global museum of the world’ . Everything arrived here by sea first and foremost, and the seas connect us all. The whole world is here – but not all our stories are visible. Where might my story be?

Early encounters

I wanted to fully immerse myself in the collections, and I had already started to reflect upon my practice as an independent artist and practitioner in relation to this opportunity.

It was interesting to view my starting point as ‘Artist Researcher’, coming into this space from an artistic perspective as opposed to a solely academic one. However, my practice and socially engaged work has always required research, which I love and which has fuelled me constantly. Libraries, museums, galleries, books and places of learning have always been hugely important to me as part of my intellectual, creative and cultural diet and also as a lifelong learner. I absolutely loved diving in and engaging with the collections at different sites within Royal Museums Greenwich.

My first stop of many was the Queen's House, where I had the opportunity to go on a guided tour with one of the curators.

The Queen’s House is a beautiful and a female space, having been Henrietta Marie’s homestead and domain. Although a woman of high status and wealth, she was not permitted to enter the political arena like her husband as she desired, simply because she was a woman.

However, Henrietta Maria established and asserted her own power as a patron of the arts and culture, commissioning artists and designers to make work. She even reshaped the Queen's House itself, instructing architect Inigo Jones to design a new north terrace facing the River Thames. I found this to be wonderfully empowering; her legacy lives on to this day.

I was also captured by the thread of blue, sailor craft and the materiality of artefacts such as the tapestries inside the House. The reverse of these works – what's going on at the back! – shed light on the process of making, and the complex weaving of visual narratives.

The Van de Velde studio, invoked as a workspace as part of a special exhibition, was also intriguing to me, featuring as it did a working ship model used for experimenting and testing. I noticed the numerous paintings of ships in storms and battles on the oceans. The violence, the drama, the expression of dominance and the navigation of power in all its forms were clearly evident.

Inside the Van de Velde studio

An evocation of the Van de Velde studio in the Queen's House. Around 1673 the room was given to the Willem van de Veldes, father and son, to use as an artist's studio. Very few details are recorded of how they used the space, which has seen various changes in the centuries since they were first here.

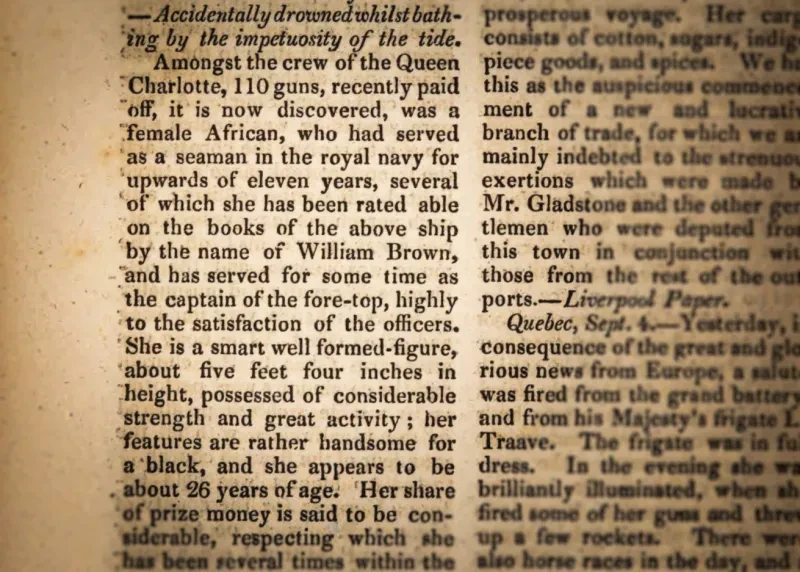

I knew from the outset that I was interested in seeing ship models, maps, illustrated logbooks and navigational charts, but I didn’t have a central theme or question yet in mind. I was also keen to explore different life experiences at sea, and I had the opportunity to listen to some oral histories experienced by black people. These powerful narrations conjured up deep visualisations for me. I recall feeling both excited and hugely overwhelmed by the magnitude of the museum as an archive.

Going on guided tours with key museum staff was a key part of my research journey, both to see what resonated with me but also to allow questions and thoughts to arise. I was happy to allow myself to be a learning observer, asking questions and collating notes from my observations.

I also had to navigate how I was going to undertake the actual research, employing my own tools and methodologies for recording and collating my findings.

As an artist and educator, and being naturally curious, I already had a range of tools in my arsenal. 'Researching' is essentially another act of rummaging: a quest for adventure, exploration and discovery!

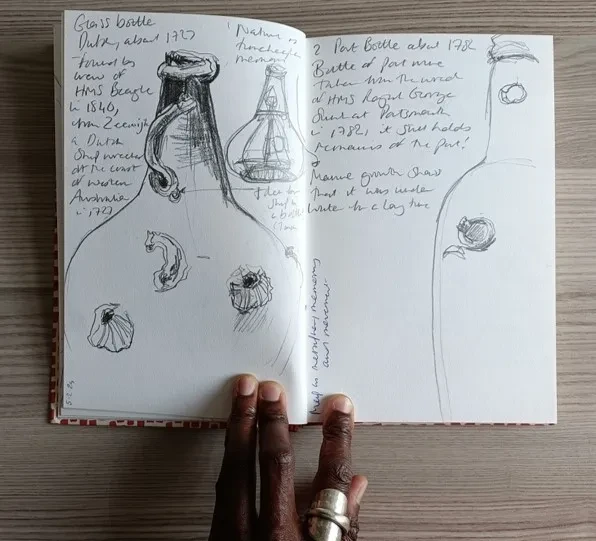

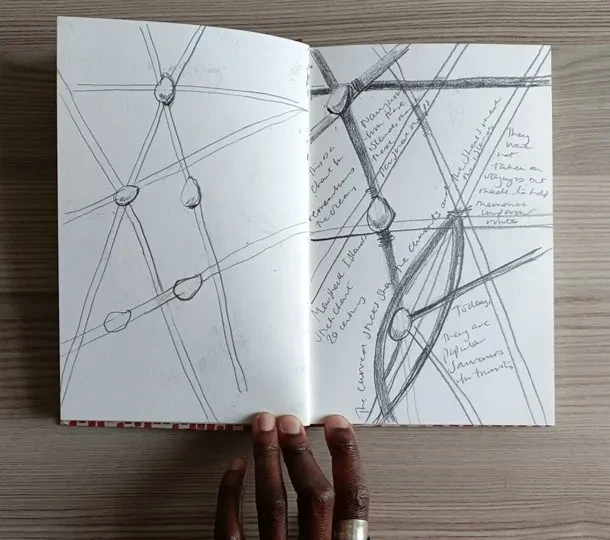

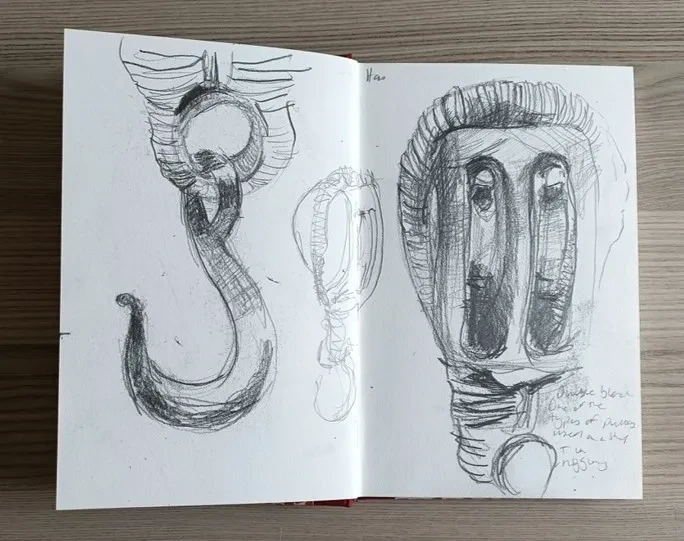

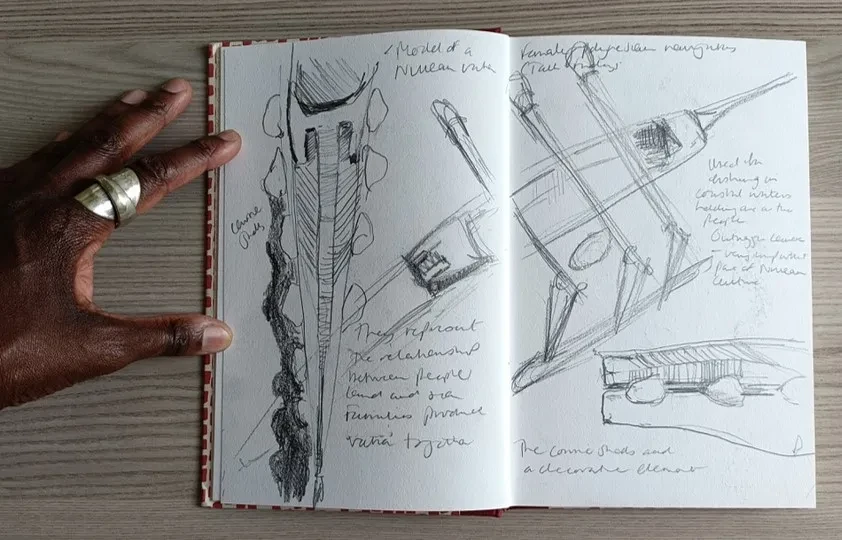

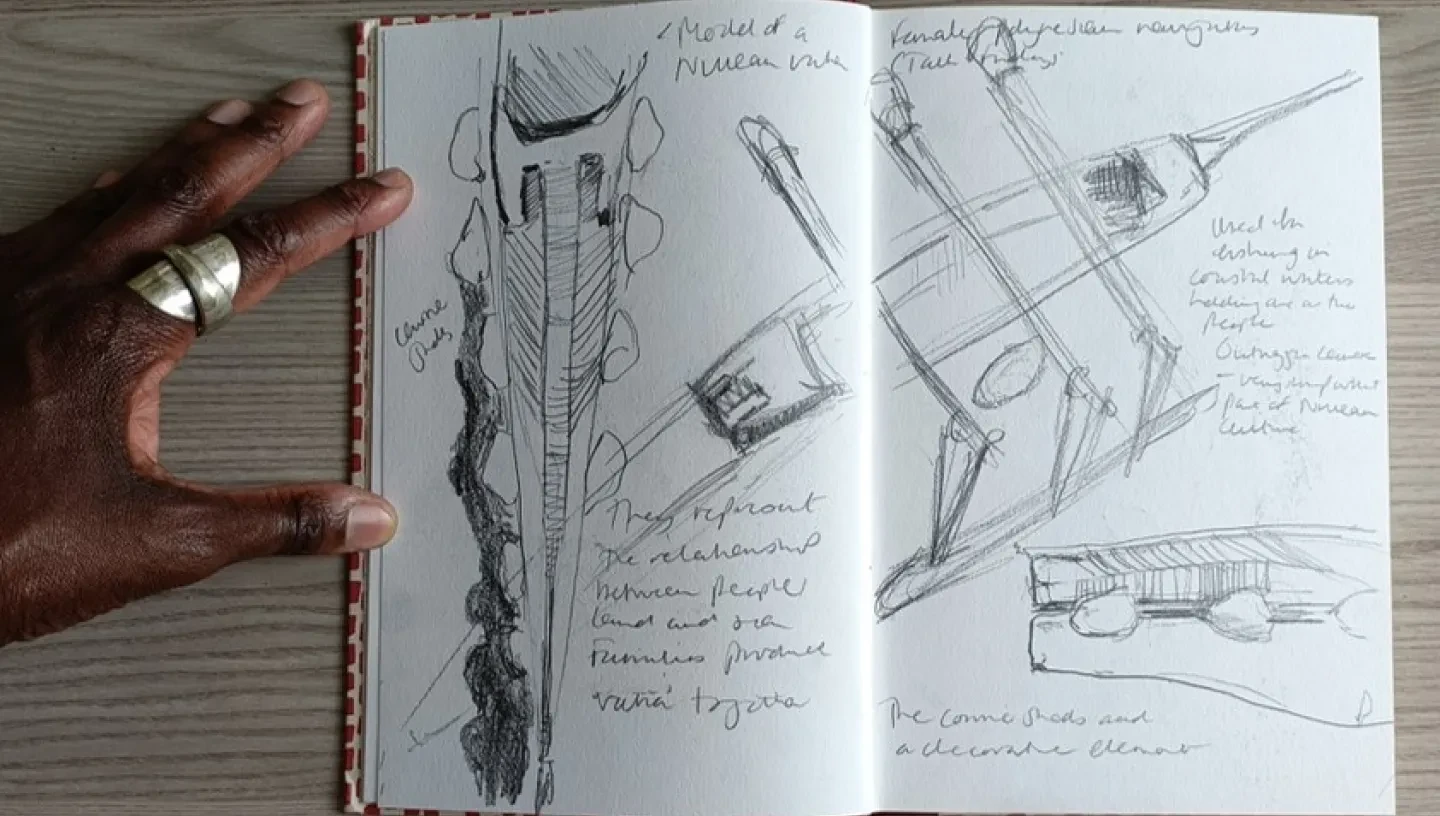

In this age of the digital I began to record my journey using my trusty notebook: pen and paper. I created mind maps and recorded my thoughts, insights and questions on a daily basis. I also started a sketchbook to make quick observational studies of objects with notes, thoughts and ideas as I explored the galleries.

Sketching history

See pages from some of Remiiya's sketchbooks featuring observations made during her research.

It is interesting to think about these notebooks in the context of the National Maritime Museum. Ship logs and journals played a hugely invaluable role as a document recording sightings and happenings at sea. In the present we gain an insight of what different parts of the world looked like at the time, but also how people lived and worked.

As an artist too, keeping and recording ‘visual data’ through drawing and writing in a sketchbook or notebook is a central core of my practice – pen and paper always! It was a wonderful way of recording but also responding intuitively to what resonated at the early stages of this journey. Sometimes it’s the purpose of an object, the story behind it, a point of inspiration or stimulus for further research. Sometimes it's about an object's textures, its construction or design. These are just some of the compass points that draw my attention.

Sketching is also a form of collating primary research material through my own observation by my own hand. It acts as an ongoing visual data log with some ideas to be developed further. During my research I had the wonderful opportunity to view a sketchbook by John Brett, which had some beautiful pencil drawings of boats and associated people such as dock workers.

To find out where my research took me next, click here.