For more than 20 years, artist Luke Jerram has enchanted audiences around the world with his celestial installations.

His multidisciplinary works include Museum of the Moon, Mars and Gaia – a giant depiction of the Earth from space. These stunning pieces have been featured in spaces from the Natural History Museum and Trinity College Dublin to the Commonwealth Games in Australia and the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing.

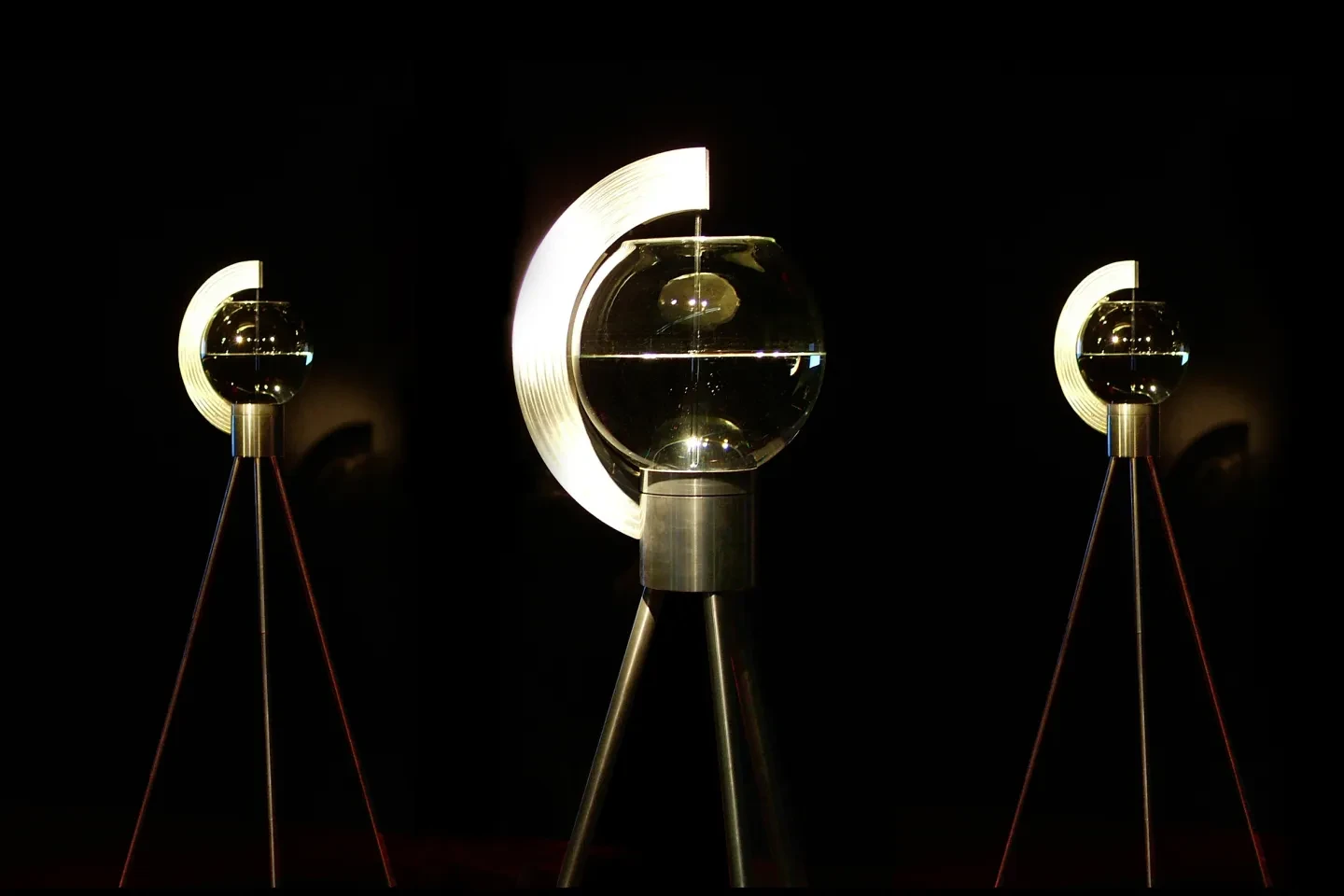

To celebrate 350 years of the Royal Observatory, Jerram has created an exclusive version of his work Mirror Moon. Made from stainless steel, this artistic interpretation of our celestial neighbour will go on display in the Meridian Courtyard from May 2026. Visit, and you can get up close to the lunar surface – touching craters, valleys and mountains – and reflect on what the Moon means to you.

Here, Jerram shares the process of creating the artwork, the varied symbolism of the Moon – and why tactile art is so important.

Why does the Moon capture your imagination?

I grew up in the countryside in the Cotswolds, which had beautiful night skies. I always wanted a telescope but could never afford one, so I became interested in the idea of making my own Moon that I could see up close.

The Moon has inspired mythologies, music, religion and poetry around the world. I find it fascinating how it's been interpreted in so many ways, whether as a god, a planet, a light source, timekeeper or a point of connection.

Mirror Moon is the latest in a series of lunar artworks I’ve created, which include Tide (2001) – a live sound installation controlled by the Moon’s gravitational pull – and Museum of the Moon (2016). This giant inflatable sculpture brings together light, lunar imagery and surround sound.

As I’ve toured my art, I’ve gained an insight into how different cultures and regions respond to the Moon. When I took Museum of the Moon to India, 100,000 people turned up on one night to see it, because the Moon has massive significance in Hinduism.

However, when I toured the installation around the USA, people associated it with the Apollo missions. In France, romantic couples sat in deckchairs beneath it and held hands. I’ve enjoyed experiencing how local cultures see the world in different ways.

What are some of the key ideas behind 'Mirror Moon'?

The Moon has been a destination for mankind for 200,000 years, yet it’s always been slightly out of reach.

Mirror Moon will enable people to see and feel the craters, valleys and mountains on the lunar surface. We only see one side of the Moon from Earth, so this installation will allow the public to go around it and explore its ‘far side’. If you’re partially sighted, you'll also be able to experience the Moon and touch its detailed surface.

I like artworks that are accessible and allow people to engage with them in all sorts of ways. That’s why the installation is called Mirror Moon: the Moon is a cultural mirror to society. It reflects the ideas, dreams and beliefs that people bring to it, so it was important that the installation was made from mirrored stainless steel.

How did 'Mirror Moon' come together?

The first iteration of Mirror Moon was developed during a residency at COSMOS Community Observatory St Martins on the Isles of Scilly. Mirror Moon at the Royal Observatory is a larger version, and measures two metres in diameter. Like many of my works, it utilises imagery and data from NASA, specifically from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission.

Creating Mirror Moon has been quite a journey. The first step involved making a digital model and then printing the design in 3D sections to make a mould. A wax version was created, which was cast in metal and polished. The whole process took around four months.

How does it feel to have 'Mirror Moon' on display at the Royal Observatory?

I feel very lucky to have the opportunity to create a new artwork for the Royal Observatory – an institution that is a beacon of science.

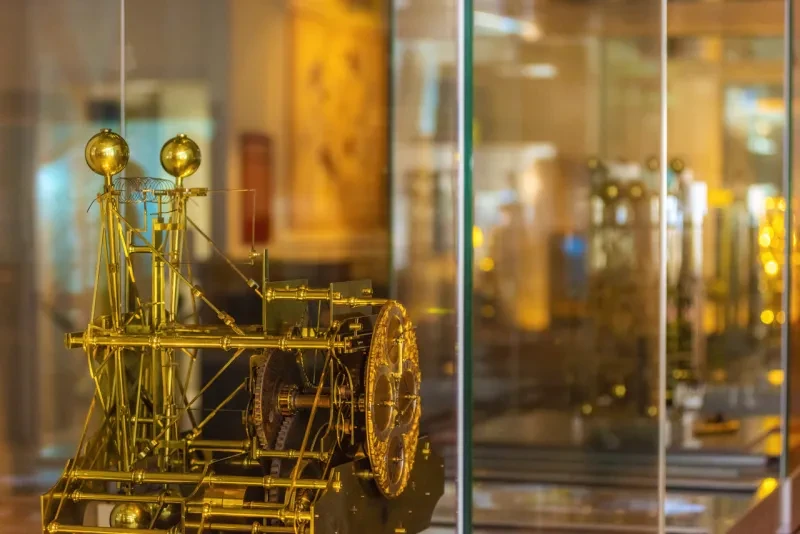

The Royal Observatory contains extraordinary artefacts, which have influenced my art. My sound artwork, Harrison’s Garden, brought together 1,000 timepieces inspired by John Harrison’s clocks. I also visited the Observatory when developing the ideas for Tide.

I like making artwork that can be appreciated by different people at various levels. I hope Mirror Moon will be inspiring and make people think about science and art together. If you’re a child, you’re going to enjoy experiencing it one way, whereas if you’re an astronomer, you’ll appreciate it in another way.

After seeing my works, I’ve had a small child come up to me and say: “Will you put the Moon back afterwards?” I’ve had astronomers in tears, as they’ve been able to see lunar features they’ve only ever studied with a telescope or a computer.

I couldn’t have asked for a better place or location for Mirror Moon. Despite our differences, the Moon connects us all.