150 years ago, HMS Challenger departed England on a quest to explore the world's oceans.

Three and a half years later the ship returned, bringing with it the largest collection of examples of life from the deep sea.

In her new book The Challenger Expedition: Exploring the Ocean's Depths, Royal Museums Greenwich curator Dr Erika Jones reflects on a groundbreaking expedition for ocean science – and how its findings still shape our understanding of the planet today.

The history of HMS Challenger

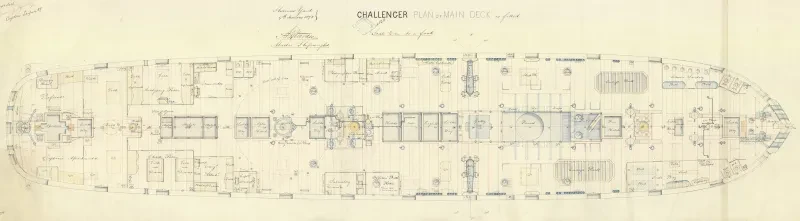

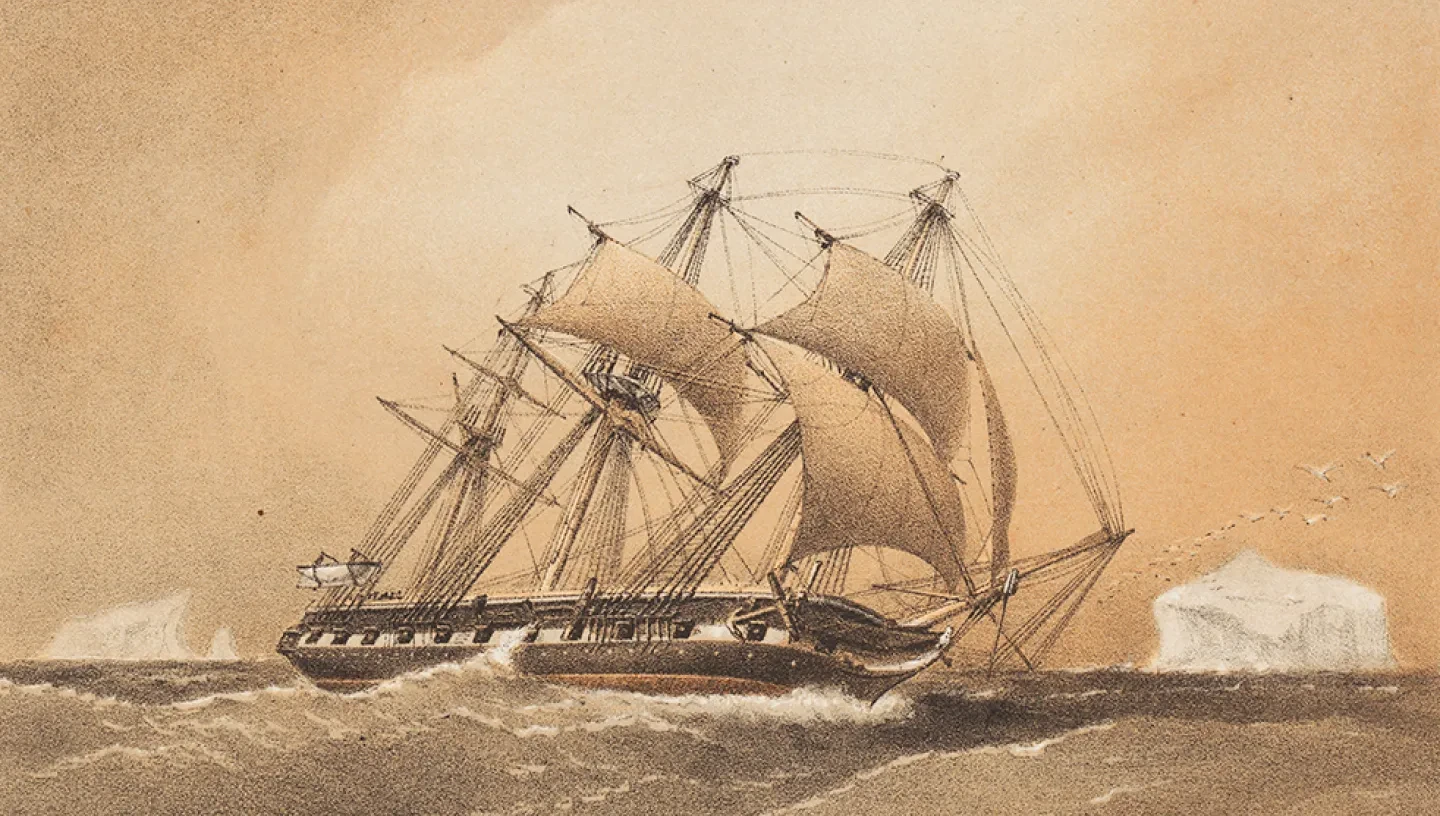

Funded by the British government and taking its name from the Royal Navy vessel specially converted for the purpose, the Challenger Expedition (1872–76) was the first to explore the deep sea successfully on a global scale.

The history of the Challenger Expedition and its scientific report provide insights into the advance of oceanography as a modern scientific discipline, a definitive moment in our understanding of the ocean as a complex ecosystem on which all life on Earth depends.

HMS Challenger departed Sheerness on the north Kent coast on 7 December 1872, under the command of Captain George Strong Nares and with a remit to explore the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the deep sea.

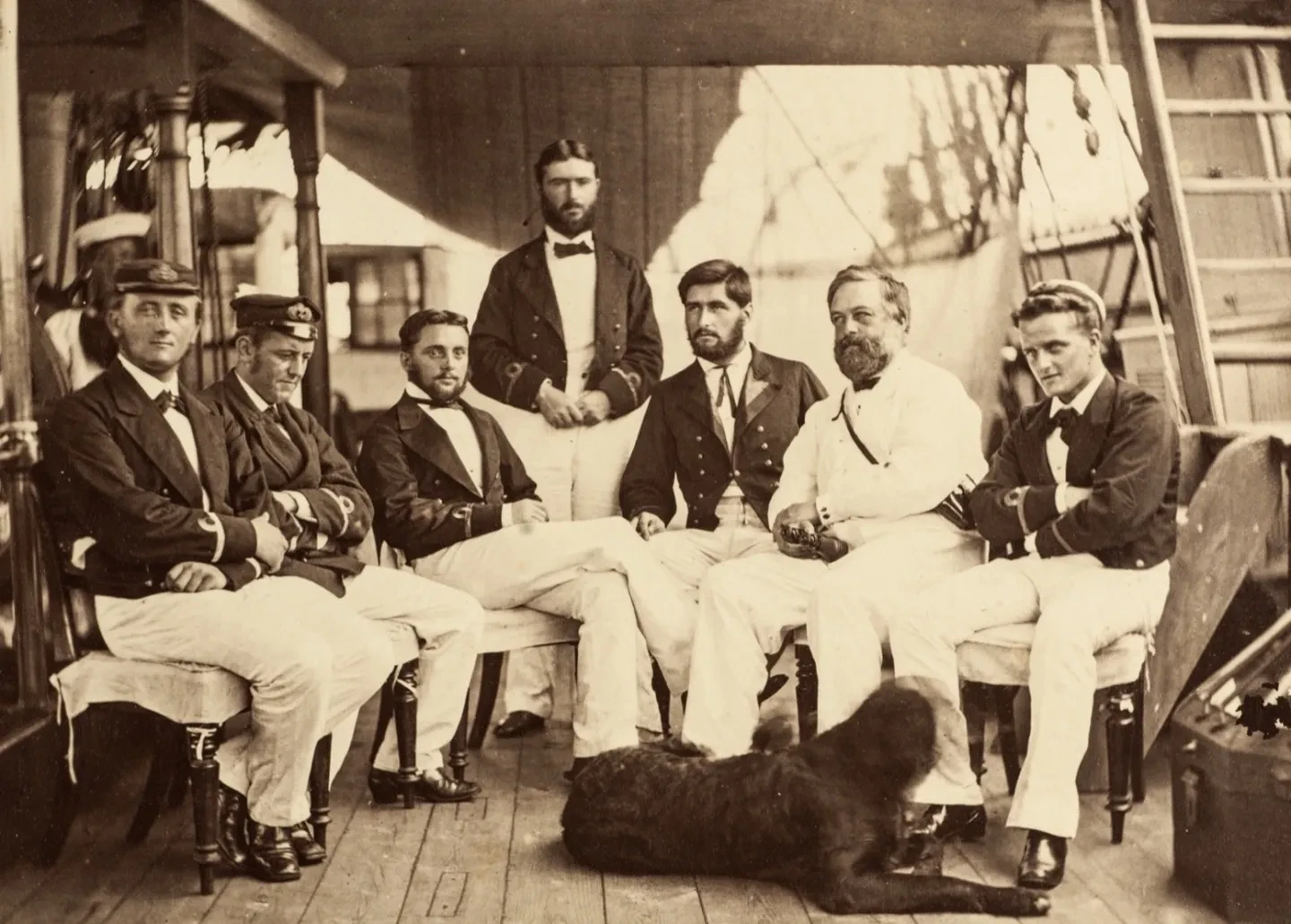

In addition to the ship's company of almost 250 sailors, engineers, carpenters, marines and officers, there was a six-person civilian scientific team led by Charles Wyville Thomson, a Scottish naturalist determined to prove that life existed in the deepest parts of the ocean.

We are to visit in succession almost every navigable part of the globe, making a complete circuit of the world and discovering no end of curious and scientific things

Navigating Sub-Lieutenant Herbert Swire

At the time, many within the scientific community doubted whether anything could survive the enormous pressure, cold and darkness of such depths. Others speculated that the ocean floor was covered in a type of primordial ooze, a substance named Bathybius haeckelii, connected to the origins of organic life.

Challenger's discoveries

Over three and a half years, Challenger's circumnavigation encompassed some 68,890 nautical miles (127,580 km) across the Pacific, Atlantic and Southern Oceans, and traversed the Antarctic Circle. During the voyage, the expedition carried out oceanographic experiments at 504 stations, observing currents, water temperatures, weather and surface ocean conditions.

Along its route, the expedition performed 374 deep-sea soundings, took 255 observations of water temperature, successfully deployed the dredge at 111 stations and completed 129 trawls. Water samples, marine plants and animals, sea-floor deposits and rocks brought up from the deep were carefully preserved on board the ship and sent to Britain for later study.

Between 1880 and 1895, with additional funding from the government, Thomson, and later John Murray, published the Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–76 as a 50-volume series from offices in Edinburgh.

Over 75 authors from Britain, Europe and the United States were involved in analysing the specimens and data amassed by Challenger and writing the reports. Enriched with information gathered by subsequent voyages, at its completion the Challenger Report formed a comprehensive study of Earth's largest and most complicated biosphere. The publication included aspects of marine biology, physics, chemistry and geology, branches of knowledge that would come together to define oceanography as a new scientific field.

The ocean floor beyond the continental shelf was shown not to be a featureless expanse, as many had previously assumed, but instead was characterised by underwater mountain ranges, abyssal trenches and extended plains. The ocean itself consisted of warm and cold water zones, a finding that added to the understanding of ocean currents and the distribution of marine life.

Although Challenger's chemist John Young Buchanan debunked the theory of primordial ooze, the investigation of the sea floor led to Murray's discovery of extra-terrestrial particles ('cosmic spherules') in deep-sea sediments. In addition, almost 5,000 new species were found and described, proving that life did exist in the deepest parts of the world’s oceans.

By the end of the voyage, the Challenger Expedition had assembled the largest assortment of deep-sea animals to date. The collection proved the abundance and variety of marine life throughout the oceans. The expedition's readings, measurements and records also created a valuable historical benchmark that climate change scientists still refer to today.

The legacy of HMS Challenger

Challenger was a trailblazer and our capacity for understanding the ocean has since been extended by technological advances. Researchers now deploy submersibles, sonar, high-tech buoys and remotely operated vehicles to probe deep-sea environments. Over the past decade, high-resolution underwater video cameras have enabled scientists and the public to view marine life as never before.

British Antarctic Survey engineer Carson McAfee introduces Britain's latest polar research vessel, the RRS Sir David Attenborough

Oceanographic research continues as an international project that calls for ships at sea and laboratories on land, but also relies on less conspicuous labours and resources, including harbour facilities, electronics factories and satellite navigation systems maintained by the United States, Russia, the European Union and China.

As we strive to understand our blue planet, a more inclusive history of ocean science is relevant to how the ocean is studied today. Everywhere Challenger travelled, the expedition acquired knowledge from those who lived in tandem with the sea or along the coast. The innovations and practices of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are of fundamental importance in informing strategies for conservation and sustainable, equitable use of marine resources and are increasingly recognised as such.

We have reached a crucial moment in our history. The unprecedented decline of biodiversity and marine habitats, caused by growing pressures from human activity, pollution and climate change, has become the most pressing environmental concern of our time. Whole ecosystems are on the verge of destruction.

Never before have we had such an appreciation for and insight into the bounty of life and mosaic of forces that constitute the ocean, a realm once beyond human observation. Today, our greatest challenge is to act upon this knowledge – to support the critical efforts being made to protect the vast ocean ecosystem and ensure the future well-being of humanity and all life on Earth.

This article is an edited extract from The Challenger Expedition: Exploring the Ocean's Depths by Dr Erika Jones, Curator of Navigation at Royal Museums Greenwich.

The book, published to mark the 150th anniversary of the expedition's launch, reveals the often hidden efforts and collaborations at the heart of HMS Challenger's landmark endeavour, the legacy of which shaped the development of ocean science for years to come.