Women's histories are relatively few and far between when it comes to the Royal Observatory pre-1950, in contrast to the number of famous male astronomers and public figures who are still lauded today.

For centuries, women were largely excluded from the field of astronomy, often only able to help male astronomers with the time-consuming recording or 'computing' of celestial data.

However, despite the limitations placed on them by their gender, a number of women managed to forge careers for themselves in this male-dominated environment. This includes Caroline Herschel, the first woman to discover a comet, and Annie Maunder, a pioneer in the field of solar research and imaging.

Below, we shed light on some of the histories of just some of the women connected with the Royal Observatory.

Louise de Kéroualle (1649–1734)

Louise de Kéroualle helped spark the race to find longitude, and encouraged the founding of the Royal Observatory.

After being appointed lady-in-waiting to King Charles II’s queen, Catherine of Braganza, Louise became one of Charles' many mistresses and was later named Duchess of Portsmouth.

The Stuarts' global ambitions coupled with the dangers of navigation made the challenge of finding longitude at sea of pressing importance. The Royal Society, created by Charles to advance science, urged him to build an observatory to research more accurate astronomical data that could help provide a solution.

However, plans were not progressing and so Louise tried to end the bureaucratic mess by introducing Charles to a French astronomer, Sieur de St. Pierre, who claimed he could calculate longitude.

The 27-year-old John Flamsteed, who would become the first Astronomer Royal, tested St. Pierre's method and found that it, just like other contemporary suggested methods, worked in theory but not in practice.

The infrastructure needed in order to find the data was lacking: namely, an observatory. This convinced the King in 1675 to sign the warrant to build the Royal Observatory, Britain’s first state-funded scientific research institution.

Margaret Flamsteed (c.1670–1730)

The first woman seriously involved with the life and work of the Royal Observatory was Margaret Flamsteed, wife of the first Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed.

Margaret Flamsteed was well educated, both literate and numerate. We know from Flamsteed's records that she occasionally assisted during observational and calculating work, and manuscripts in the Royal Greenwich Observatory archive in Cambridge show that she studied mathematics and astronomy.

These studies may have reflected those of Flamsteed's paid assistants and paying pupils, men and boys that Margaret would have taken care of as part of the general management of the household on Greenwich Hill.

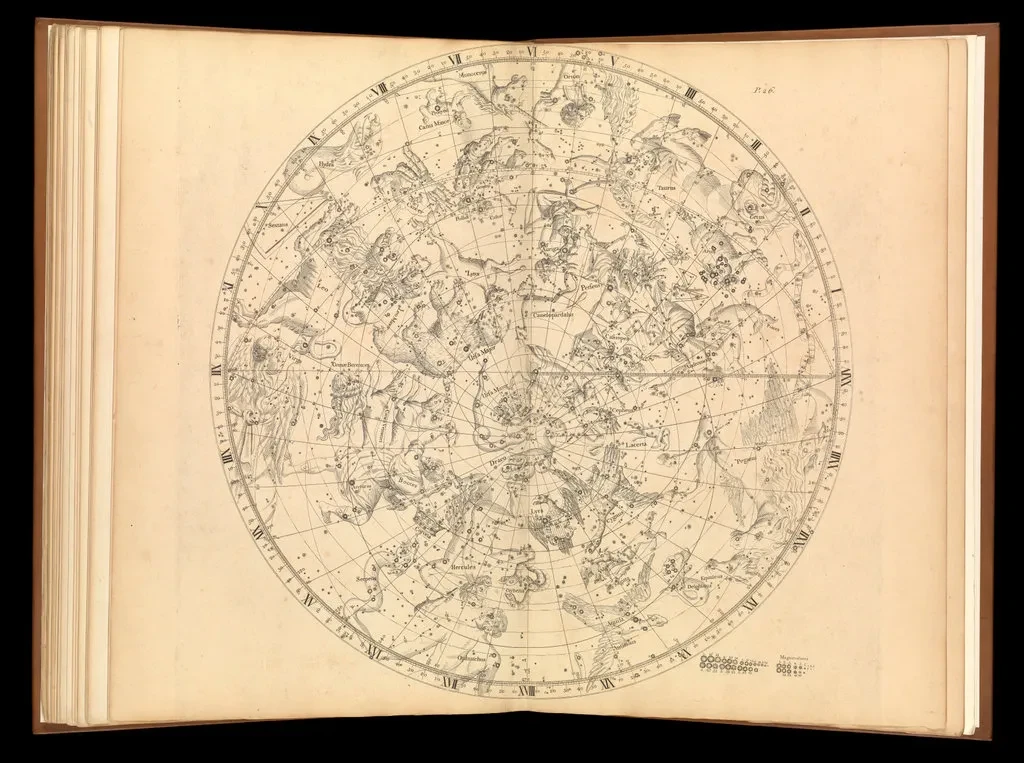

It is, however, as Flamsteed's widow that Margaret is best remembered. After John died she worked with the Observatory's former assistants to publish the full version of his book, Historia Coelestis Britannica, in 1725, an abridged version of which had been published against John's wishes by Edmond Halley in 1712.

She also oversaw the publication of his Atlas Coelestis in 1729. Without her these important works, which would be used by future astronomers for decades, may never have been published.

Caroline Herschel (1750–1848)

Caroline Herschel was a German-born astronomer who overcame the limitations placed on her by her gender to become an accomplished member of the astronomical community.

She started out in astronomy when her brother William Herschel took it up as a hobby and discovered Uranus, earning the patronage of King George III.

Caroline was subsequently paid a salary by the King to be William's assistant, making her the first woman in Britain to earn a living from astronomy. However, she also undertook important astronomical work of her own.

She achieved a lot during her lifetime, including becoming the first woman to discover a comet, revising John Flamsteed’s star catalogue, and cataloguing more than 2,500 nebulae.

Read more about Caroline Herschel

Margaret Bryan (1759–1836)

Margaret Bryan was a British author and astronomer who taught Natural Philosophy to girls and young women from her self-run boarding schools in Margate, Blackheath and Chelsea.

Margaret wrote three books in her lifetime, each funded by subscribers from the highest tiers of Georgian Society, including notable academics, royalty, politicians, and religious leaders. In an era before mass media, Margaret’s networking skills enabled her to share her teachings with schools, libraries, and bookshops across the UK, reaching a broad audience and cementing her reputation as a credible female scientist.

The respect and affection for Margaret was such that her portrait hung on the study wall of William Herschel and her first book A Compendious System of Astronomy, In a Course of Familiar Lectures (1797), opens with a letter of recommendation from the celebrated mathematician Sir Charles Hutton of the Royal Academy, who refers to her manuscript as ‘ingenious’.

Margaret’s second book Lectures on Natural Philosophy (1806), offers teachings on hydrostatics, optics, pneumatics, and acoustics. It lists the Duke of Sussex as its principal subscriber alongside many other distinguished figures, including former Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne.

Margaret also endorsed a popular astronomy-themed board game called ‘Science in Sport’; a copy of which is in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection. In the game, players aim to reach the final 'square' depicting Flamsteed House and take the title of Astronomer Royal.

Alice Everett (1865–1949)

Alice Everett attended Queen's College, Belfast, where she took first place in the first-year scholarship examination in 1884, despite the fact that women were not eligible for scholarships at the college.

She then attended Girton College, Cambridge, the first women's college at the university, studying the Mathematical Tripos.

Beginning work as a supernumerary computer at the Royal Observatory in 1890, Alice was assigned to work in the Astrographic Department, contributing to the international Carte du Ciel project which aimed to map the skies using the still-new technique of stellar photography.

Although her job title was 'computer', Alice was trained to take photographs using the Observatory's new astrographic telescope, as well as measuring the plates, calculating the coordinates of the stars and reducing the data for the catalogue.

Alice was proposed but rejected for fellowship of the Royal Astronomical Society and instead found an outlet for her enthusiasm in the amateur British Astronomical Association.

After five years at Greenwich, Alice moved to the Potsdam Observatory, Europe's leading institution for astrophysical research, to continue work on the Carte du Ciel. She later turned her focus to optics (the study of light), undertaking a translation of a German optical text and carrying out a number of experiments.

However, she was unable to find regular paid work until the First World War, which gave women more opportunities within the workforce. In 1917 she joined the National Physical Laboratory, where she remained until her retirement in 1925.

Annie Maunder (1868–1947)

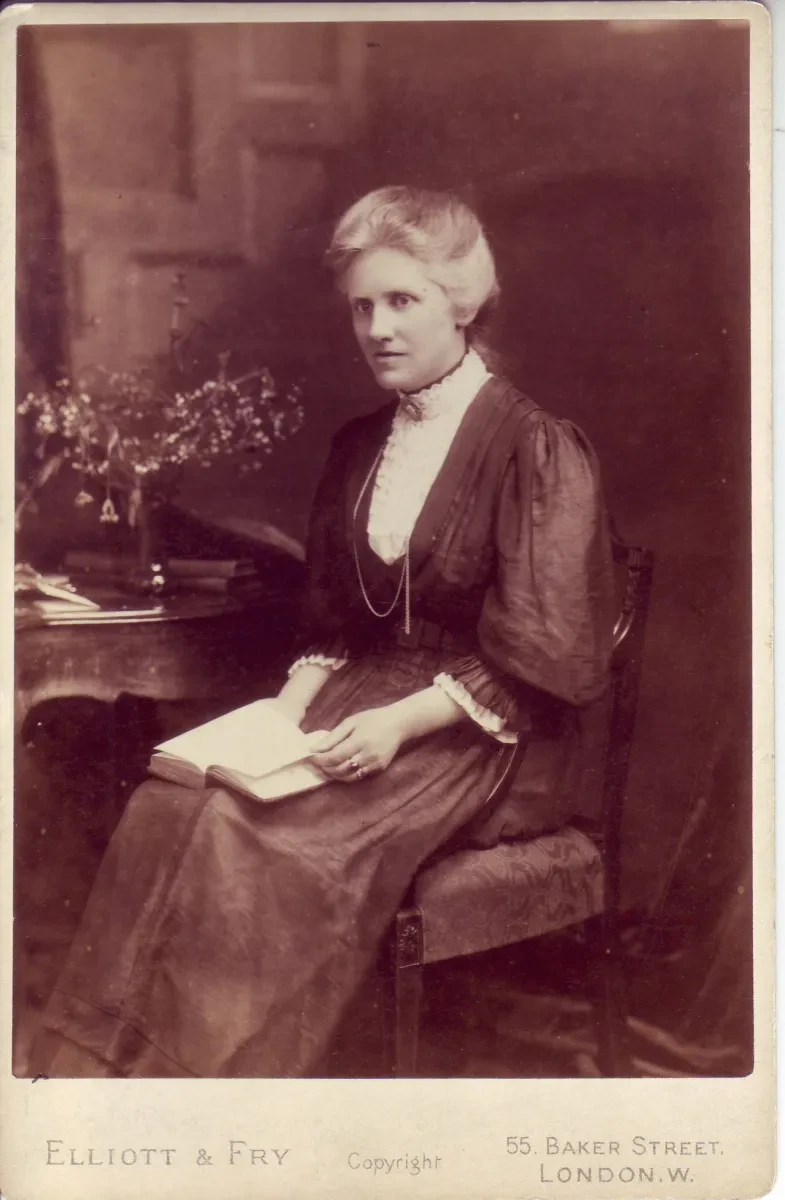

Annie Maunder was an astronomer, astrophotographer and science communicator.

Like Alice Everett, Annie studied the Mathematical Tripos at Girton College, Cambridge. Despite completing the exams in 1889 she left with no formal recognition, as Cambridge did not award full degrees to women until nearly 60 years later.

Annie joined the Royal Observatory in 1891 as a computer, where alongside completing mathematical tasks she was assigned to work in the Solar Department, and began taking daily photographs of the Sun to record sunspots.

After several years in post, Annie married the head of the department, Edward Walter Maunder, which meant as a married woman she had to resign.

Undeterred, Annie continued to participate in astronomy in a voluntary capacity, particularly with the British Astronomical Association (BAA). She and Walter went on eclipse expeditions to a variety of places worldwide, using telescopes and specially-adapted cameras to capture details of the Sun’s atmosphere.

Working together on their sunspot data, among other achievements the Maunders compiled decades’ worth of observations to create the renowned ‘butterfly diagram’ that showed how the locations of sunspots shift, a diagram still useful today.

Annie and Walter were well-known among amateur astronomers as public lecturers and writers, with Annie becoming one of the first female Fellows admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ruth Belville (1853–1943)

For 48 years, Ruth Belville sold accurate time from the Royal Observatory to London.

Every week, Ruth would go to the Royal Observatory with an 18th-century pocket chronometer in her handbag.

She would set the chronometer against the standard clock at the Observatory before making her way around 30-40 customers spread across London, who paid for a weekly visit from the 'Greenwich Time Lady' so they could keep accurate time.

Ruth kept up her rounds despite the challenges of the First World War, the installation of new telegraph wires all over London, the beginning of the 'BBC pips' and wireless communication becoming more widespread and reliable.