The historian leading the search for HMS Captain questions why the sinking of 'one of the finest ships in the world' is not better known today.

Travelling to Wales in 1832, a 13-year-old Princess Victoria described Wolverhampton in the rapidly industrialising West Midlands as ‘a large and dirty town’.

The region, she wrote, was ‘very desolate everywhere, there are coals about, and the grass is quite blasted and black’. Then again, she also noted how her entourage ‘were received with great friendliness and pleasure’.

Having lectured at its fairly modest but proud University for 20 years now, I can affirm that we tend to punch above our weight.

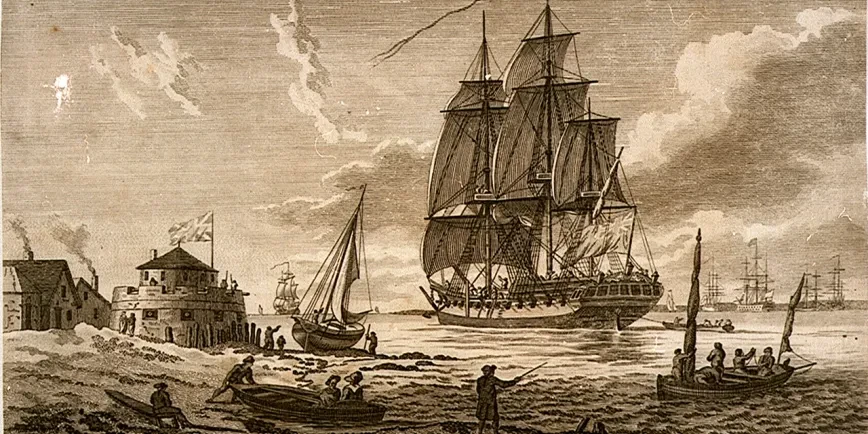

Although we are 70 miles to the nearest beach, as landlocked as it gets in England, the University of Wolverhampton’s Centre for Historical Research has set out to find the wreck of the legendary ironclad HMS Captain, which foundered in a gale off the coast of Spain on 7 September 1870.

For more than four years our Find the Captain Project has worked to identify the exact location of HMS Captain. We have scoured ships' logs, survivors’ accounts, court-martial testimonies and other sources to determine the position of the ship when she sank. In 2022 an exploratory marine survey off Cape Finisterre scanned a previously unidentified shipwreck, which showed a general configuration approximate to that of HMS Captain. Our next goal is to return and make a positive identification of this tantalising ‘mystery wreck’.

But beyond the immediate and imposing task of discovering this lost Victorian man-o’-war, Find the Captain is even more about rediscovering the vessel’s place in history.

The most famous warship you've never heard of

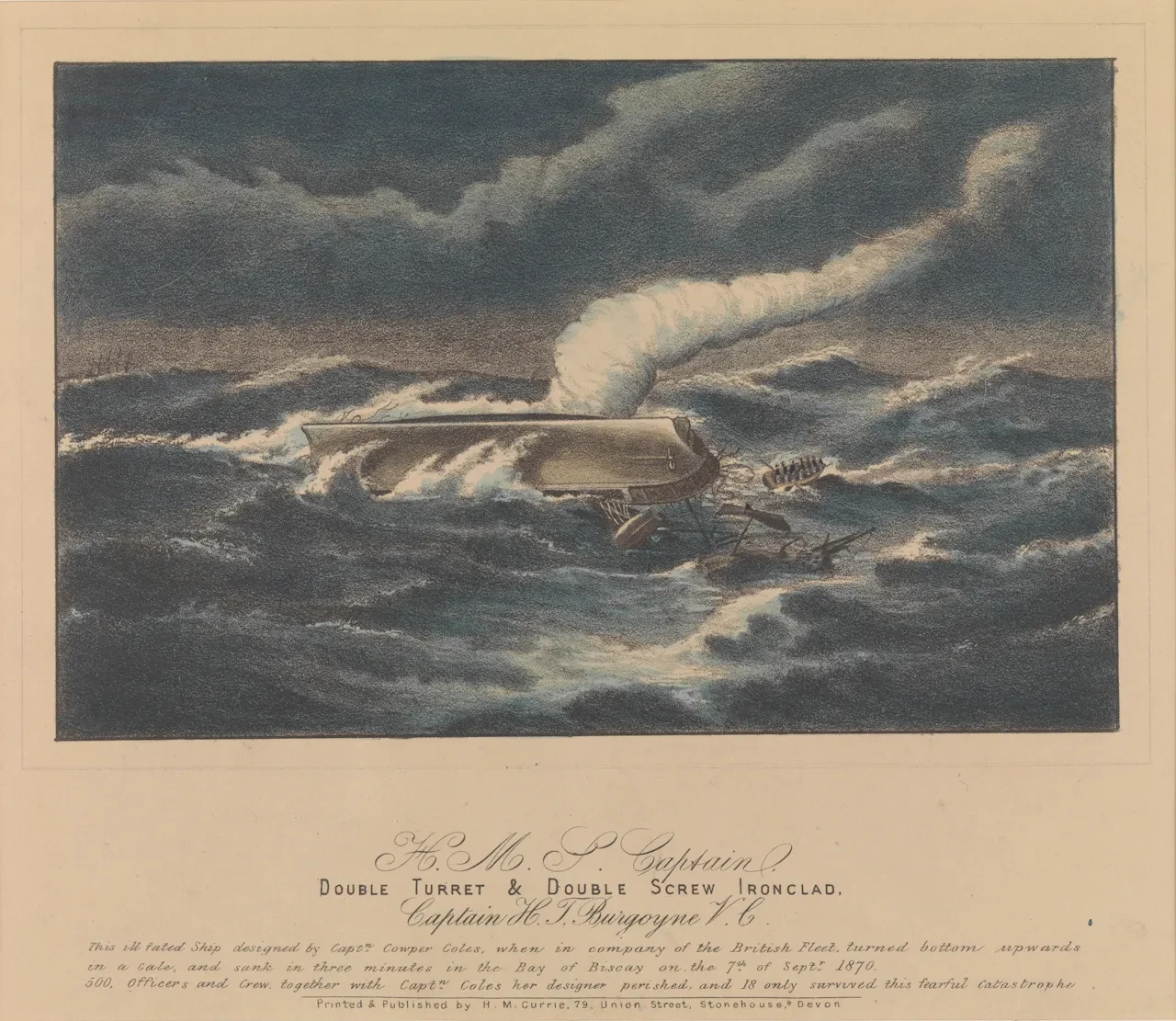

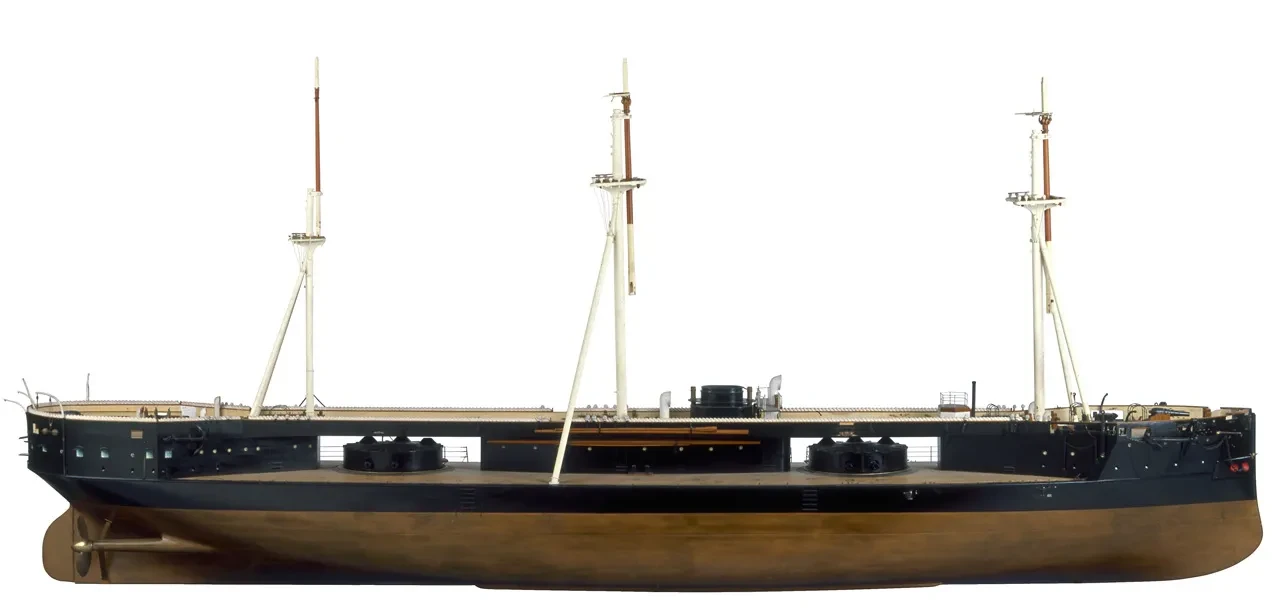

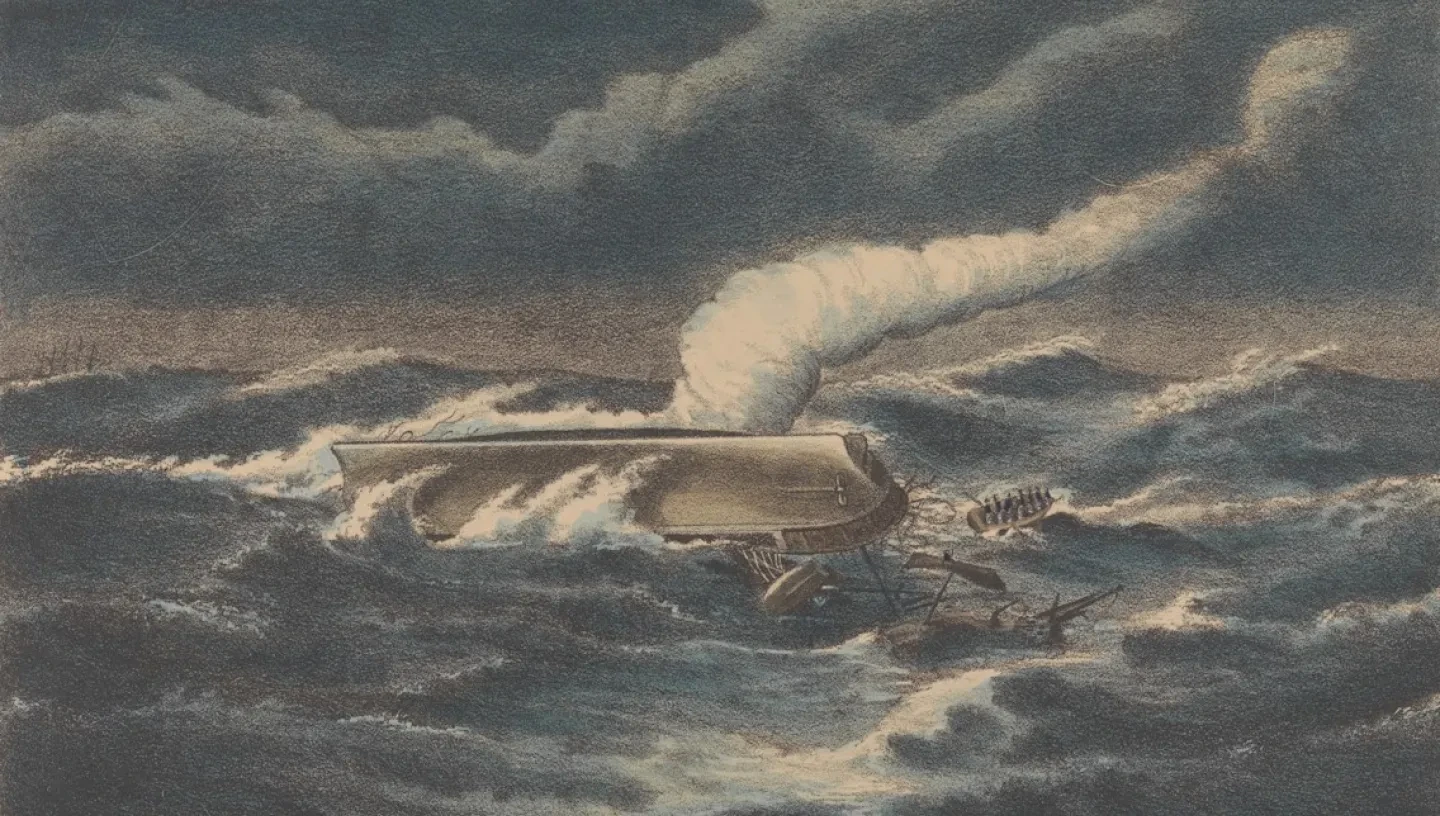

Nearly the entire crew of 500 men went down with this dangerously low freeboard yet fully rigged turret ship, including her controversial designer, Captain Cowper Phipps Coles. ‘Few such terrible disasters have ever happened at sea’, exclaimed The Times. ‘A greater number of lives may occasionally have been lost in a single wreck; but this wreck is that of one of the finest ships in the world, manned by one of the finest crews.’

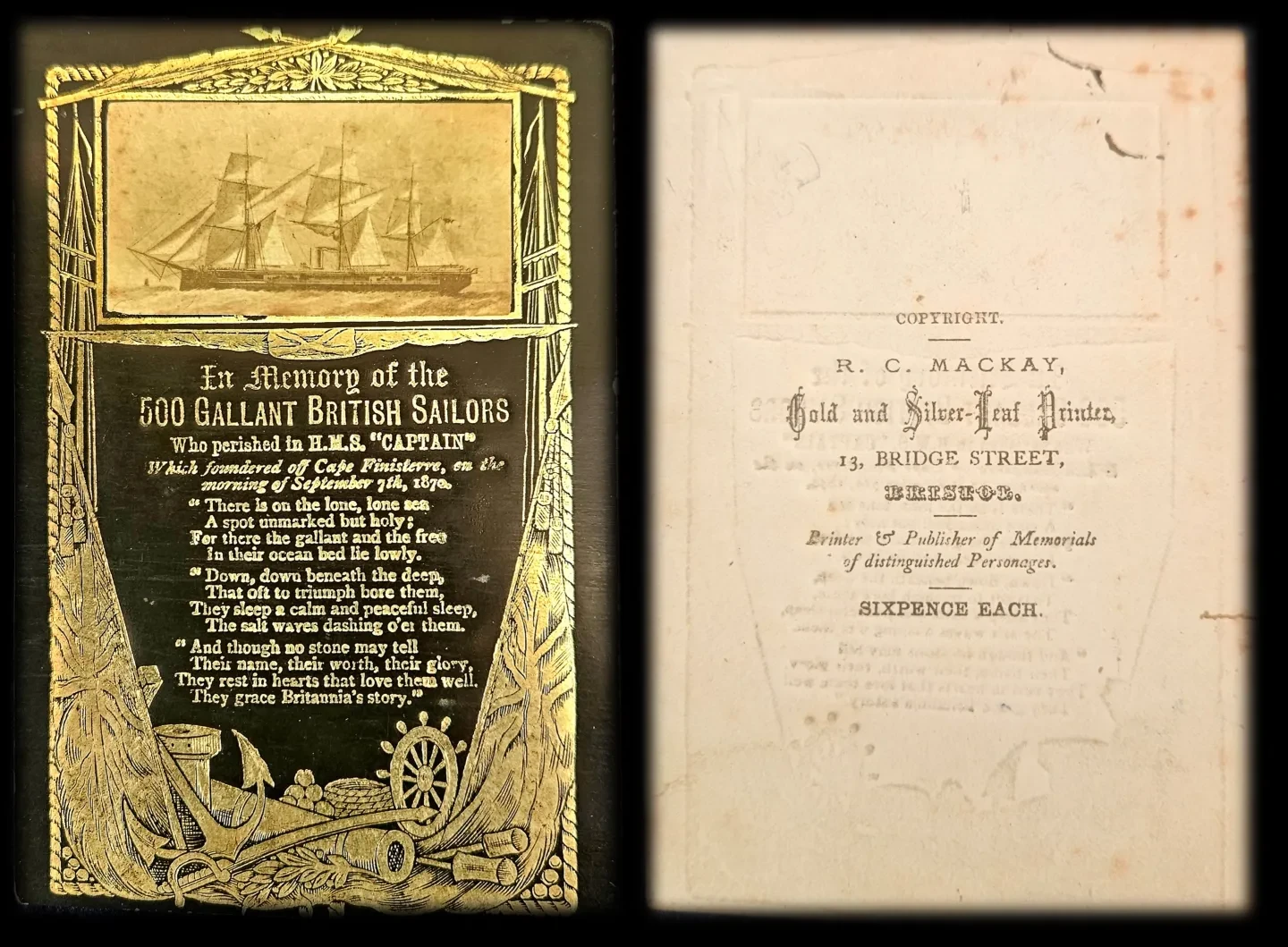

Indeed, when the Captain keeled over in 1870 it was the worst fiasco suffered by the Royal Navy since the Napoleonic Wars and remained that way well into the twentieth century. Her loss was commemorated with large brass plaques in St. Paul’s Cathedral as well as a stained-glass window in Westminster Abbey. Both gestures were unprecedented and have never been repeated.

As such, we have a bit of mystery. We’re talking about an epic tragedy at sea with potentially serious implications for Britain as ‘Mistress of the Seas’. And yet today ironclad HMS Captain is the most famous British warship we’ve never heard of.

The Captain cover-up

So part of our challenge in finding the Captain goes beyond the sizeable funding support required for marine survey operations or working closely with the Spanish government (the shipwreck we’ve scanned but not yet identified is just within their territorial waters).

The clamour surrounding this particular maritime disaster at the time quickly turned into something so politically divisive, so bitterly personal, that soon everyone involved – from government ministers to trauma-stricken families – became eager to put the memory of the whole damned thing behind them.

Captain became a black ship in British national memory, an Albatross. Indeed, despite ‘Captain’ being famous as Nelson’s go-to command at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent (14 February 1797), no Royal Navy vessel has carried the name since 1870.

Historians have meanwhile tended to gloss over this appalling episode in naval technology, treating it as an aberration, a footnote in a rather deterministic narrative of British naval supremacy during the ‘Pax Britannica'. HMS Warrior of 1860 may have been ‘Queen Victoria’s deterrent’, but the Captain of 1870 was designed to take up her mantle, complete with guns in rotating turrets. One revolutionary, state-of-the-art warship survived; the other spectacularly did not.

It took 93 years before a British journalist, Arthur Hawkey, told the story of HMS Captain. His absorbing 1963 account cast designer Cowper Coles as the flawed character responsible for an otherwise avoidable catastrophe. This rendition remains firmly embedded, and it took another 57 years before my academic research monograph, Turret versus Broadside (2020), sought to analyse the wider ‘why?’ of HMS Captain and Coles for the first time. This explored the geopolitical as well as technological context of the decade, which undermined Britain’s self-confidence to the point that Coles and his followers would have had any influence upon Admiralty shipbuilding policy in the first place.

Only two books on the Captain in the past 155 years? A run-of-the-mill university in the West Midlands takes up the search for her wreck because no one else has bothered?

Fate or folly?

Perhaps more to the point for historians is how people reacted to catastrophe and why, and what that tells us about them as people.

The mid-Victorian generation was a remarkable combination of faith in scientific and social ‘progress’ and Christianity. On the one hand, people demanded a rational explanation for the tragic sequence of events that led to the foundering of Britain’s newest and most powerful capital ship. Someone had to be held accountable, if only to prevent such errors in planning and execution from being repeated in the future. Hugh Childers, the First Lord of the Admiralty, had lost his youngest son to the Captain. Lessons needed to be learned.

On the other hand, many were simply fatalistic and pointed to natural or ‘divine’ phenomena beyond mortal man’s arrogance – especially when it concerned the treacherous sea. ‘There but for the grace of God go I…’

Was the sinking the result of a causal chain of human error or stormy Fate? Or was it somehow both?

The 'value' of a shipwreck

We’re determined to find the Captain. But locating a historical artefact is about much more than the shipwreck itself.

In the end, it's nothing more than a long-lost mass grave site. A pragmatist would say that unless it’s filled with gold doubloons it’s nothing more than a rusty piece of metal – and that the past itself is all but irrelevant.

But here we might beg to differ. The ‘Ship’ is just the beginning: the beginning of a story. The story is about people long ago, but also their whole world, their own time. And eminently useful, necessary abstractions like ‘Time’ and the ‘World’ are arguably what helps give life (and death) meaning.

Perhaps discovery and close examination of the wreck will even change the established narrative. Was the ship fitted with bilge keels or not, and would that have made a critical difference? Should we commission the Wolfson Unit at the University of Southampton, fresh from their analysis of the Bayesian’s capsizing, to re-examine the Captain’s stability? Would any vessel in the ironclad squadron that night have survived the focused blast of a random cyclonic downburst – if that’s what actually happened?

Asking questions and telling stories is what drives history. Once the most powerful seagoing battleship in the world, the Captain – and its dramatic tale – is little known today. We want to tell the stories of the men on board, unite the descendants of the crew who were lost – and survived – and highlight how the relentless pursuit of global power might, at times, come at a terrible price.

About the author

Dr. Howard Fuller is a Reader in War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and was previously a Caird Research Fellow and the Rear Admiral John D. Hayes Fellow in U.S. Naval History through the U.S. Naval Historical Center (now Naval History and Heritage Command) in Washington, D.C.

He is the author of Clad in Iron: The American Civil War and the Challenge of British Naval Power and Empire, Technology and Seapower: Royal Navy Crisis in the Age of Palmerston (Routledge, 2013). He is also the Editor for the International Journal of Naval History.

His latest research monograph, Turret versus Broadside: An Anatomy of British Naval Prestige, Revolution and Disaster 1860-1870 (Helion & Company, 2020), was the first comprehensive academic study of the Captain tragedy. Since 2021 Dr Fuller has also been the founder and project manager of the University's 'Find the Captain' Project (https://findthecaptain.co.uk).

Join museum experts online for a voyage across the world’s oceans, and explore the legacies of our seafaring past.