The Royal Navy developed some of Britain’s earliest welfare schemes in order to look after disabled and aged seamen.

The Caird Library and Archive hold the correspondence sent between the Board of the Admiralty and the Sick and Hurt Board (ADM/E, ADM/F and ADM/FP).

These letters offer a glimpse into how the Royal Navy administered disability claims and provided welfare for naval servicemen.

This article explores what happened to seafarers who were declared 'unfit for service': what support was available, and how was it accessed?

A second blog, available here, documents the process of invaliding itself.

Content warning: this blog contains content which may cause distress. Some of the historic language expressed is considered offensive, and its presence is not an endorsement of the terms. This language has been retained to reflect the historical context of the times.

Who were the Greenwich Pensioners?

Welfare support was provided to some naval workers in the form of a 'pension'.

Sailors on active service had one shilling deducted every month from their wages to fund the scheme. These welfare provisions were supplemented with unclaimed prize money and government funds.

Aged and disabled sailors could qualify for long term accommodation and care at the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich, where they became ‘in-pensioners’. Admission was strictly assessed to cater only to individuals perceived as being most ‘deserving’. Prospective candidates were referred by a surgeon or commanding officer for an ‘examination’ at the Admiralty’s offices, which occurred on the first Thursday of every month.

It is unclear what precisely occurred in these examinations, but it likely involved a review of the candidate’s service history, character references from captains or supervising officers, a physical exam, and questions about the candidate’s health and conditions.

‘Out-pensions’ were regular payments made to disabled sailors who did not live in Greenwich Hospital. The out-pension system was initially managed with the Chatham Chest, a chest held at Chatham Dockyard holding the funds to pay pensions to disabled seamen. In 1803, Greenwich Hospital took over the Chest’s administration, and it became known as the Chest of Greenwich. These payments were based on a scale that accounted for injury type and, later, length of service.

Out-pension payments were not enough to subsist on alone, and they should not be mistaken for the ‘superannuation’ payments, which offered officers a portion of their pay in retirement after a set length of service.

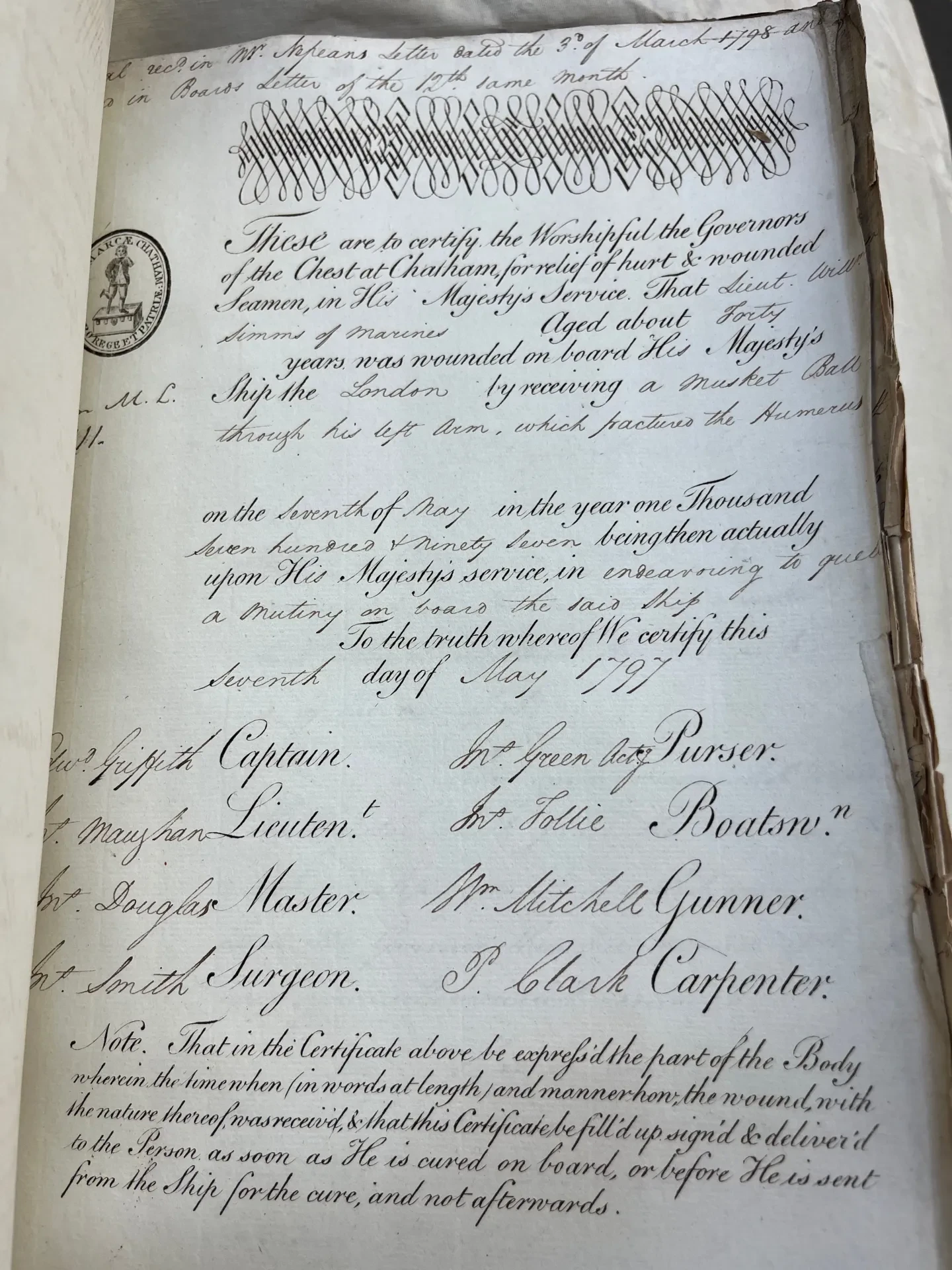

A certificate given to a 40-year-old lieutenant marine, William Simms, records that he had ‘received a musket ball through his left arm, which fractured the humerus’. The wound was sustained while quelling the mutiny aboard HMS London in May 1797, as testified with the signatures of eight officers.

This injury, acquired in the line of duty, granted him access to the Chest at Chatham, the seal of which is stamped on the upper left of the page.

An Act of Parliament, held on 3 May 1796, sought to prioritise sick pay and pensions for those ‘wounded in action’. However, the correspondence between the Admiralty and Sick and Hurt Board reveals that workers suffering from chronic medical complaints, occupational injuries and old age also received support as in-pensioners or out-pensioners.

How seafarers sought support

Most seafarers were referred directly to welfare support by surgeons, physicians, or captains as part of the invaliding process. Some seamen, however, accessed this system of welfare on their own terms by petitioning the Admiralty directly or having a family member or patron write on their behalf.

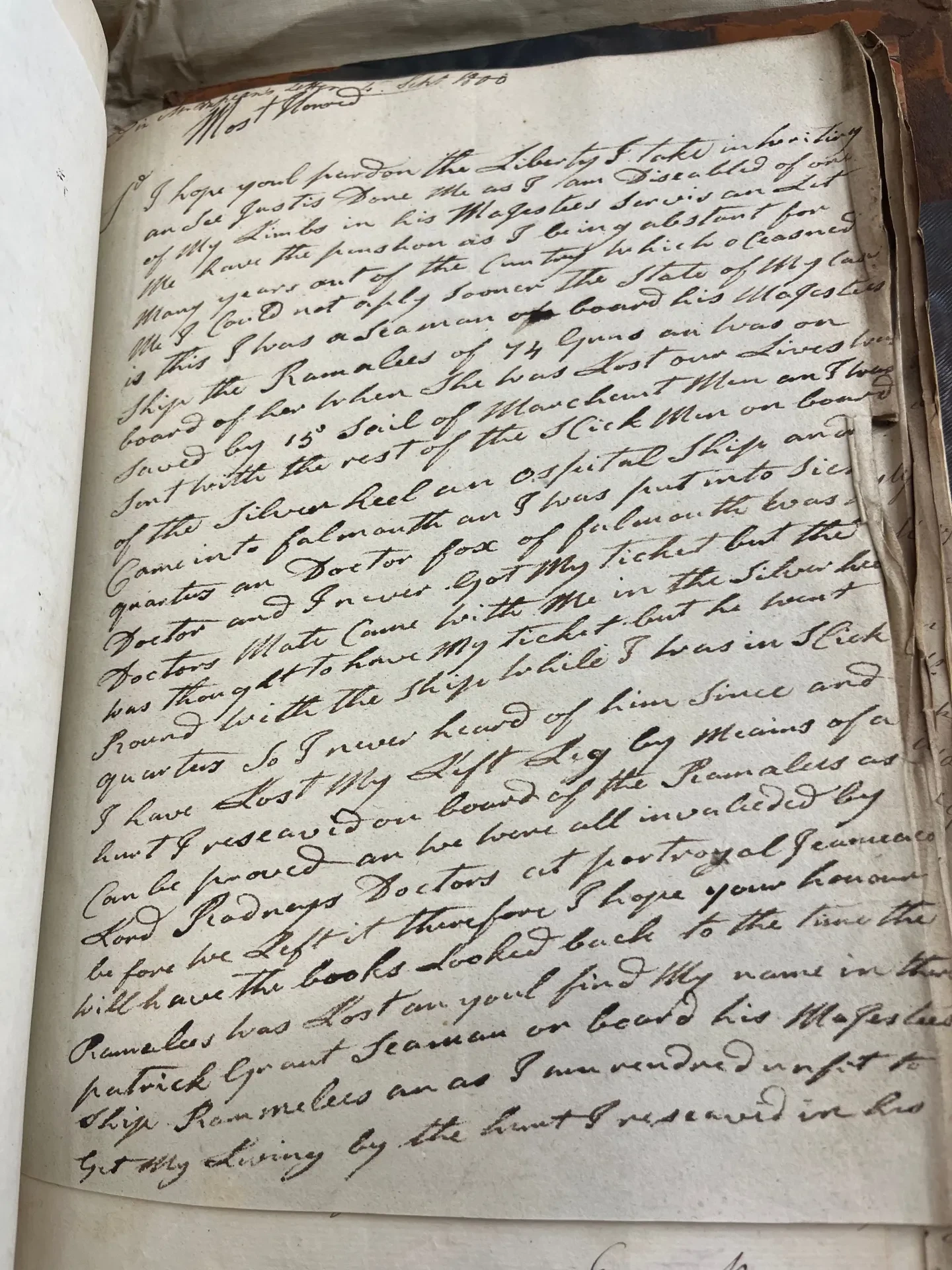

Writing in September 1800 from Manchester, Patrick Grant, a seaman formerly of HMS Ramilles, wrote to the Board to request help with his disablement:

I hope youl pardon the Liberty I take in writing an see justis Done Me as I am Diseabled of one of my Limbs in his Majestees Servis.

Grant had been given his Sick Ticket by Doctor Fox at Falmouth Hospital, but the assistant surgeon misplaced the ticket and left, leaving him with no proof of his medical examination and claim for relief.

Grant wrote that he was 'rendered unfit to get my living' and requested that the Board inquire into his case to prove his service and injury: ‘I hope your honour will have the books looked back to the time the Ramilles was Lost an youl find my name in there’.

A slip inserted next to Grant’s letter contained the messy notes of a Board’s clerk who had rifled through the Admiralty’s records to support Grant’s case: ‘8 April to 6 July 1782, invalided on board’.

Grant was writing nearly 20 years after his injury to gain support from the Navy, presumably because had managed to eke out a living up until then despite his disability.

Despite very little evidence of fraud, the Admiralty often expressed fear that seamen would try to 'game the system' by acquiring a medical discharge to get a pension. Invaliding and welfare assessments sometimes included references from captains to determine whether the individual was of 'good character'. This attempt to police 'disability fraud' reflected constructed notions of the 'deserving' and 'undeserving' poor.

Informal support outside the Navy

Not everyone received support. Many naval workers were refused welfare from the Navy due to shorter terms in service or unqualified discharges. Instead, they had to rely on informal support, such as family, charity, begging, or relief from county poorhouses and workhouses.

Occasionally we can recover traces of these individuals in the archive when they were perceived as being ‘disruptive’ to local communities. In April 1806, the Guardians of the Poor of Alverstoke wrote to the Admiralty about ‘the poor, the maimed, and disabled’ naval workers in their parish. Alverstoke was the location of Haslar Naval Hospital, so it received many of those discharged from service.

To illustrate the ‘innumerable’ invalided workers that relied on their charity, the Guardians offered the examples of Jane Morris and Ann Burke, two women who had served as nurses at the Haslar for ‘upwards of 40 years’ before being discharged and ‘thrown as chargeable on this Parish’. Similarly, John Hughes, a seaman invalided from Haslar as ‘an idiot’, was ‘delivered to the Guardians of this Parish’ by the hospital as their concern (ADM/E/52, April 1806).

It is unclear whether the Guardians were writing to complain about the burden of caring for these individuals or to solicit financial aid from the Admiralty. Whatever the case, the letter showcases the immense pressure on local communities to support the invalided workers who had been denied naval pensions.

The Admiralty also received letters from local community members about seamen and officers who were seen to suffer from a broad class of illnesses classified as ‘mental derangement’.

On 3 August 1805, Mr Clarke, a Magistrate from the County of Middlesex, reported that James Thorpe, a seaman discharged from the Zealand, had ‘committed several violent acts’. This behaviour had been linked to ‘evidence of his being insane’. Writing from the Public Office of Shadwell, Clarke inquired to the Board on ‘the propriety of confining the Man in the Hospital for insane Seamen at Hoxton’ in order ‘to prevent future mischief’ (ADM/E/51, August 1805).

In another case, Benjamin Turner, a Sergeant of the Royal Marines, was found in the local workhouse ‘raving mad’. The Vestry Clerk of St Anne’s Westminster wrote in to the Admiralty on 17 May 1804, who forwarded the letter to the Sick and Hurt Board. A few days later, the Sick and Hurt Board requested that the sergeant be sent to Bethlem Royal Hospital, a hospital that specialised in early psychiatric care in London (ADM/E/49, May 1804).

At the height of war, particularly in the years between 1810 and 1812, a large number of seamen were outsourced to asylums such as Bethlem and Hoxton due to poor mental health, which was then referred to as ‘madness’ or ‘insanity’. These asylums operated as places to confine individuals who were considered too ‘disruptive’ to integrate into local communities.

Making sense of the system

Naval administrative correspondence may at first glance appear to be a dull read but enclosed in these volumes are snapshots of the lives of maritime workers when they were at their most vulnerable. Examining these records allows historians to reconstruct the process of invalidation and the provision of welfare.

The pension system in the Navy was pioneering for its time and reveals the state’s early involvement in offering support to its workers. More importantly, these letters reveal where the system failed. Letters from poorhouses and local magistrates make clear that the Navy fell short of caring for all aged and disabled seamen.

About the author

Dr Manon C Williams is a historian of maritime health and medicine. Her research focuses on ship surgeons and the medical administration of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Royal Navy. She is currently a Caird Research Fellow at Royal Museums Greenwich, where she is investigating the invaliding process in the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815).

Further reading

- Teresa Michals, Lame Captains and Left-handed Admirals: Amputee officers in Nelson’s navy (University of Virginia Press, 2021).

- Callum Easton, ‘The Greenwich pensioners and Britain’s naval workforce, 1764–1869’, International Journal of Maritime History 37, No. 4 (2025): 1–24.

- Martin Wilcox, ‘The “Poor Decayed Seamen” of Greenwich Hospital, 1705–1763’, International Journal of Maritime History 25, No. 1 (2013): 65–90.

Join museum experts online for a voyage across the world’s oceans, and explore the legacies of our seafaring past.