People living along coastlines are understandably worried about human-caused climate change.

Aside from rising seas, acidifying oceans and changing ecosystems, they know that wild storms could blast their homes and harbours. How is human-caused climate change affecting the frequency and severity of these storms?

How do storms form?

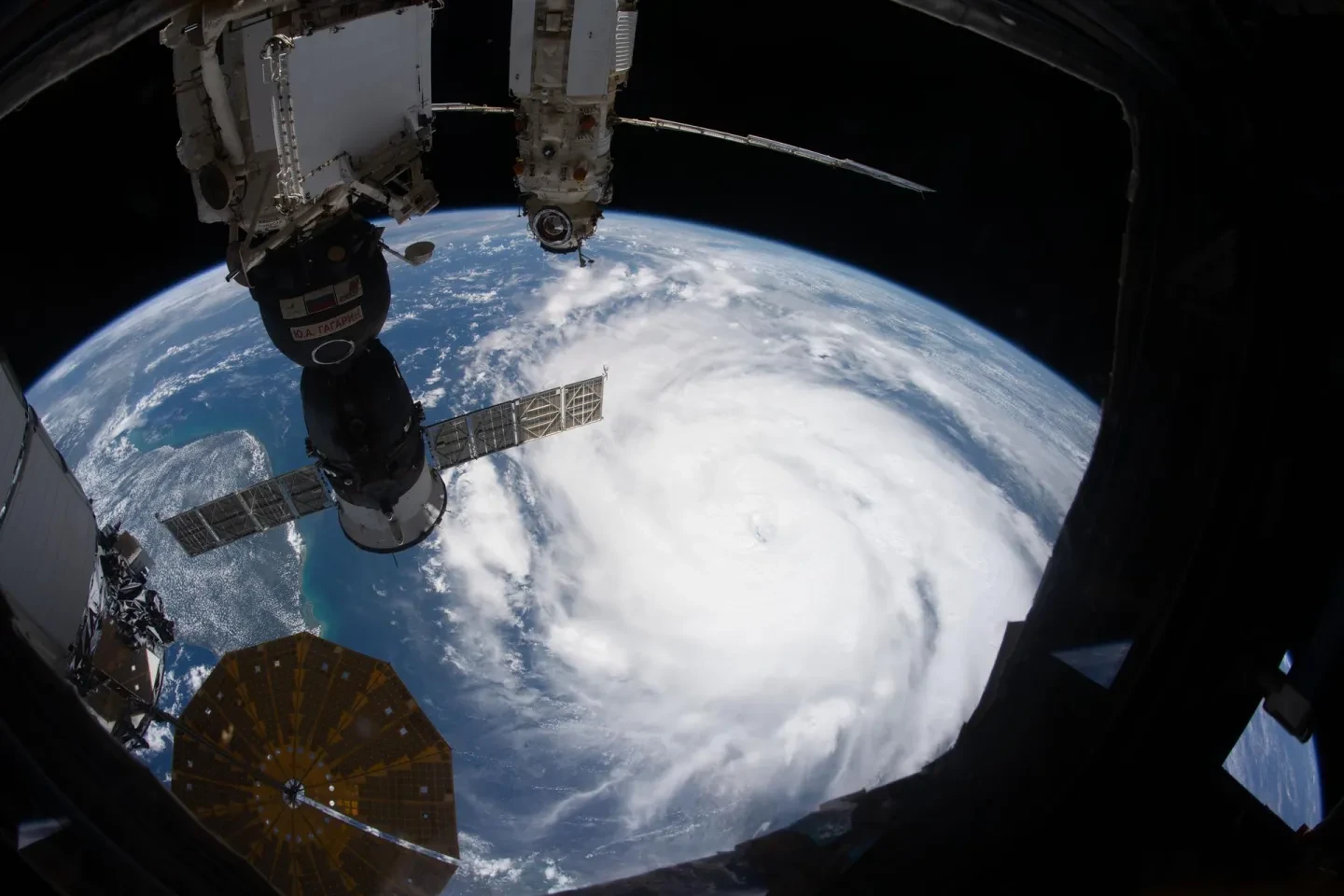

Many storms that form over the ocean end up rapidly rotating: they become 'cyclonic'.

Tropical cyclones are called hurricanes, cyclones or typhoons depending on the ocean over which they form (Atlantic/Northeast Pacific (hurricane), Indian Ocean/South Pacific (cyclone) and Northwest Pacific (typhoon)). These storms all appear around the lower latitudes – the tropical or sub-tropical oceans – although none has yet been known to start around the equator. Nonetheless, settlements near the equator can be pounded by powerful waves from tropical cyclones to their north or south.

At higher latitudes, 'extra-tropical' cyclones exist – that is, cyclones outside the tropics – and these occasionally hit the UK. 'Medicanes' (a combination of the words ‘Mediterranean' and 'hurricanes’) appear over the Mediterranean. In Arctic waters meanwhile, ‘polar lows’ are common cyclonic storms.

To reach tropical cyclone status, the maximum sustained wind speed of a storm must be 119 kilometres (74 miles) per hour or more. Below that level, they remain as tropical storms to about 62km per hour (39mph). Below that, phrases such as tropical waves, tropical depressions and tropical disturbances might be used – or we could just call them storms.

Although cyclonic storms form over the open ocean, they can track toward shorelines and make landfall. They bring strong winds and dump huge amounts of rain, and can sometimes reach hundreds of kilometres inland. Storm surges and ocean waves might race up rivers, arriving beyond the usual tidal range.

We have been dealing with these threats for all of human history.

One of the most lethal recent North Sea storm surges was during the night of 31 January/1 February 1953.

More than 300 people died on land around the UK, and hundreds more were lost on vessels in the Irish and North Seas. In the Netherlands, the storm had an official death toll of 1,836. London’s Thames Barrier and much of the Dutch approach to their coastlines today was primarily a response to this disaster.

How is climate change affecting tropical storms and hurricanes?

These storms are affected by us changing the climate. What must we be ready for?

The overall number of tropical cyclones is actually likely to decrease. One reason is that the overall temperature difference between the equator and the poles influences storm formation. The Arctic and Antarctic are warming faster than lower latitudes, so this temperature difference is decreasing.

Another possible reason, still under discussion, relates to changes in winds higher in the atmosphere. For a storm to start rotating and become cyclonic, its structure must be robust enough to overcome high winds at its apex, which can break it apart. As these winds become less stable, they inhibit storms from becoming cyclonic.

Yet when a storm is strong enough to begin rotating, it has overcome these strong winds and so it must be powerful. The number of strong cyclonic storms appears to be increasing due to human-caused climate change. Moreover, they might be intensifying more rapidly and closer to land.

In October 2023, a Pacific storm named Otis took only 24 hours to strengthen from tropical storm status to Category 5 hurricane, the most intense possible. It soon slammed into Acapulco, Mexico, leaving little time for people to prepare.

Part of this rapid intensification is driven by heat. The ocean has absorbed around 90 per cent of the heat added to the atmosphere due to human-caused climate change, mostly at the surface. Sea surface temperatures help to drive a cyclonic storm once it has formed. Warmer oceans mean stronger storms.

Warmer air also holds more moisture in the form of water vapour. When a storm dumps its rainfall, far more water is unleashed, contributing to flooding.

Hurricane Harvey stalled around Houston, USA in 2017, dropping more than 1.5 metres of rain in some locations. In 2021, Hurricane Ida made landfall around New Orleans and then swept across the USA before heading out to the Atlantic Ocean via New York. In New York City at least 11 people drowned, many of them in basements which had been illegally converted into apartments.

Fewer storms can lull people into a false sense of security. A lack of experience of tropical cyclones means people become less concerned about the possibility and therefore less prepared. Eventually however, a storm must strike. The impacts in this scenario could be more severe because the storm is stronger than expected, people have less time to be ready for it, and they have neglected preparedness.

Does climate change mean coastal storms will hit new places?

Whether or not coastal storms will affect new areas due to human-caused climate change remains an open question.

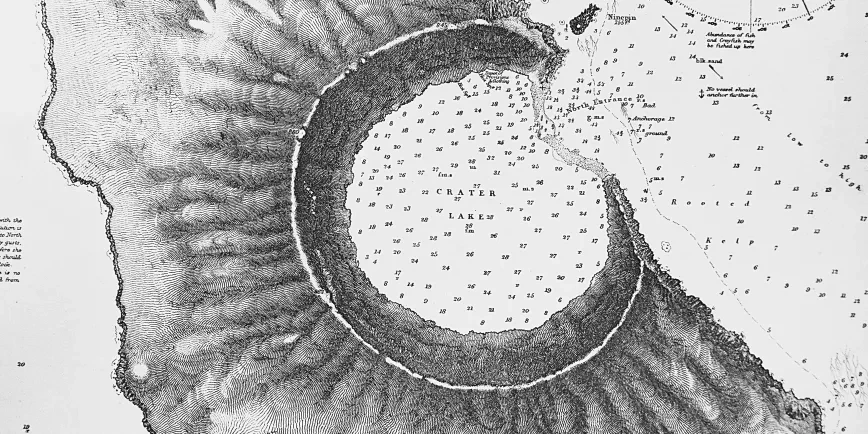

The first recorded South Atlantic hurricane was Hurricane Catarina in March 2004, making landfall in southern Brazil. ‘First recorded’ does not imply much here since complete records cover only a matter of decades. Comparable and consistent storm data for the world began more or less with satellites in the early 1970s. That is a short timeframe compared to how much the climate has changed.

We monitor and track numerous decades-long climate variabilities. Examples include the North Atlantic Oscillation, the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Despite their names identifying their ocean, they influence each other and, likely, storms globally. If other major environmental changes occur, for instance a weakening of the gulf stream, then coastal storms would be further influenced, probably by a further decrease in numbers.

Countries such as Trinidad and Tobago frequently claim they do not experience hurricanes.

Yet historical records offer a list of strikes. When eventually these islands are affected again, many will point to human-caused climate change as altering the storm tracks. Long-term observations of tropical cyclones do not suffice to make such a definitive conclusion.

Coastal storms: be prepared

Regardless of how coastal storms are and are not being affected by human-caused climate change, the usual motto applies: be prepared. Hurricane Melissa in October 2025 across Jamaica, Cuba, and Haiti shows how we ought to prepare better.

None of these countries is a stranger to powerful hurricanes. The unacceptable death toll and devastating damage show how decades of experience and lessons have not been applied to avoid a disaster. Reasons relate to corruption, failure to redress poverty and inequity, and poor leadership, driven both internally and externally.

People who live in a storm zone during storm season should be ready for storms. They often do not have options to do so, as seen during Hurricane Melissa. Given what can be done to avoid death and devastation from a natural phenomenon, even one changing due to human influences on the climate, we ought to change 'what could be done' to 'what is done'.

About the author

Ilan Kelman is a Professor in Disasters and Health at University College London and Professor II at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. His overall research interest is linking disasters and health, including the integration of climate change into disaster research and health research. He wrote the book Disaster by Choice: How our actions turn natural hazards into catastrophes.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.

Main photo by Ian Talmacs via Unsplash