As human-caused climate change affects Earth's oceans, people who depend on the sea and shorelines for their lives and livelihoods are worried.

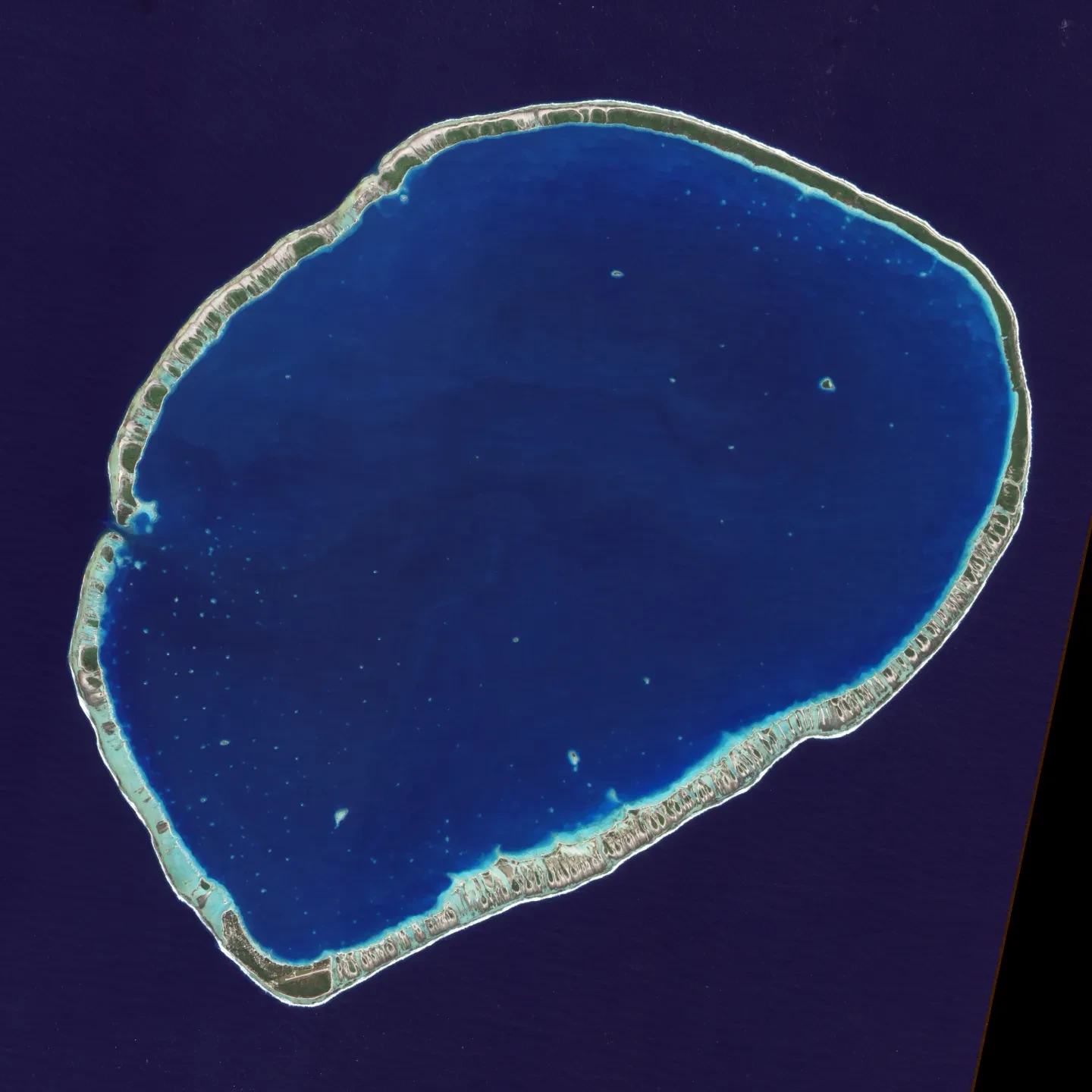

At the forefront are those living on atolls. These supposedly idyllic islands, graced with placid white sand beaches and the shadows of coconut palms, are variously labelled as eroding, drowning, sinking, or otherwise devastated by climate change impacts.

The reality is not so straightforward.

The impact of climate change on the ocean

Rising sea levels, warming waters and acidifying oceans are all consequences of human-caused climate change.

The atmosphere’s increasing temperature melts ice, snow and permafrost. This meltwater runs off into the seas, adding volume. About half of today’s rate of rising seas is caused by this melt.

The other half of current sea-level rise is due to ‘thermal expansion’. The ocean absorbs about 90 per cent of the heat added to the atmosphere due to human-caused climate change, explaining why the surface temperature of the ocean is increasing. Warmer ocean water is less dense, so it expands as it heats up. This causes sea levels to rise.

Global Temperature Anomalies from 1880 to 2021 (courtesy of NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio)

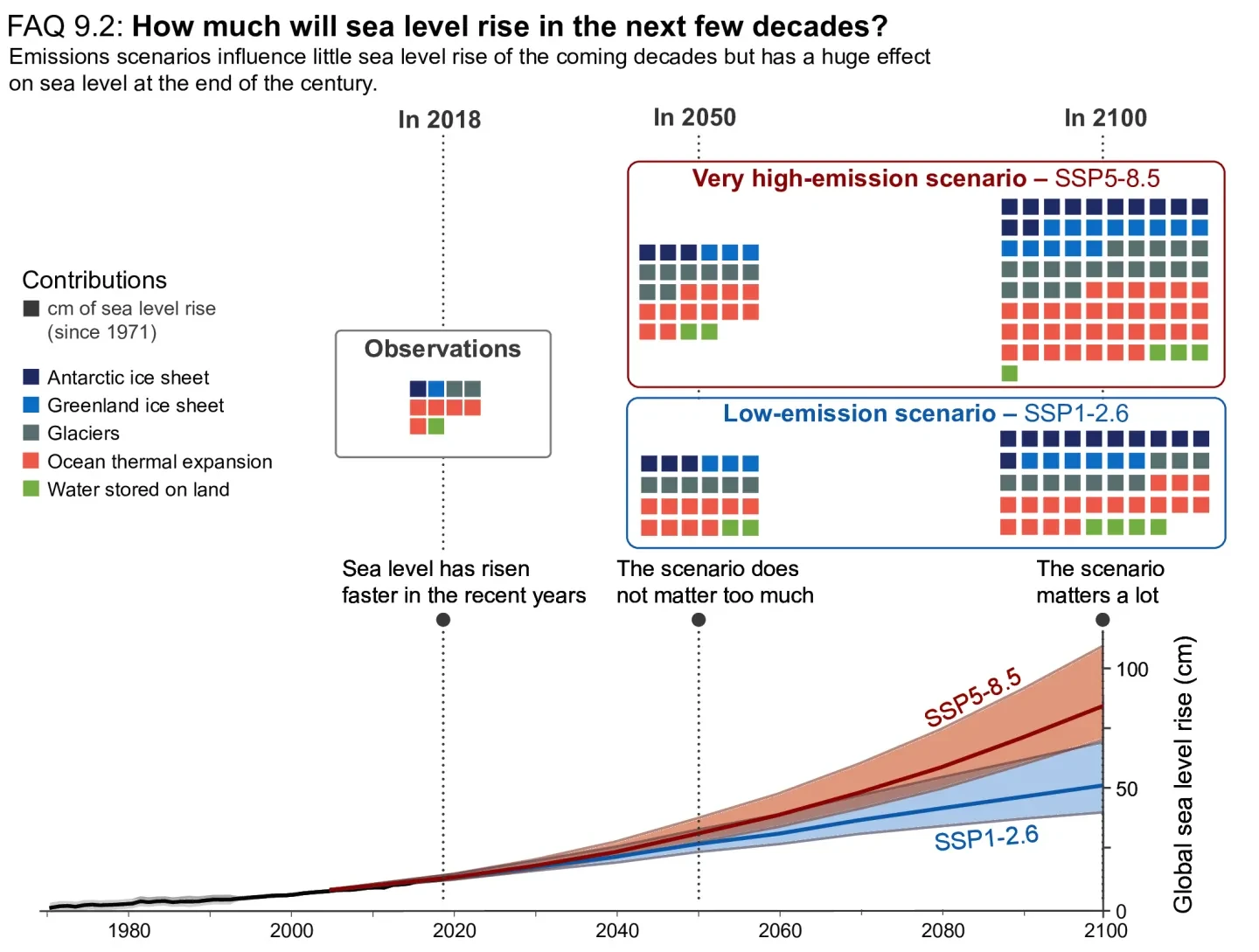

Between 1901 and 1971, sea level rose by around 1.3 millimetres (mm) per year on average. Over the past decade this has accelerated to almost 4 mm per year. If human-caused climate change continues unabated, by the end of this century the sea level is expected to be more than one metre higher than the level seen during the 1980s.

The sea-level rise story does not end here. The contribution from ice melt could increase dramatically in the coming centuries if the enormous ice sheets covering Antarctic and Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) start to melt substantially. Currently, expected melt would easily add more than 10 metres of sea level onto today’s value – higher than most four-storey buildings. In the very unlikely situation that all this ice melts, then seas would rise by dozens of metres, inundating most coastal high-rise buildings.

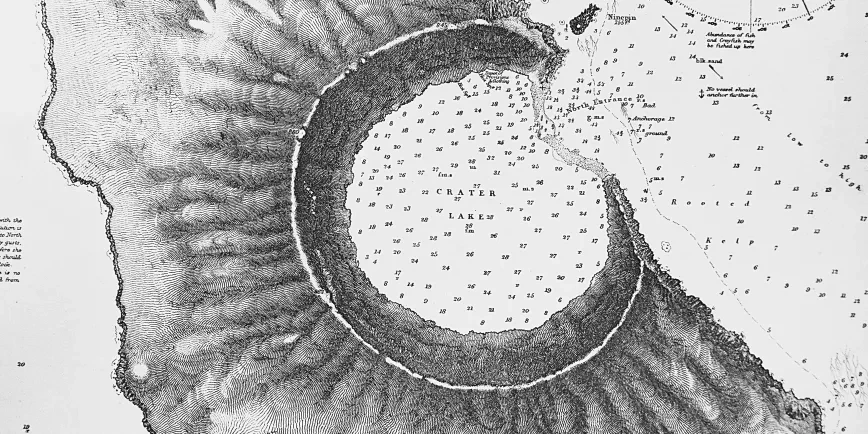

None of the numbers are consistent for the entire world. Without accounting for wind, waves or tides, the average level of the ocean varies globally by tens of centimetres. Daily, monthly, yearly and decadal tidal variations make the picture even more complex. The largest tidal range on Earth is found in the Bay of Fundy between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, where the difference between high and low tide is around 12 metres on average.

Seawater also currently absorbs about 30 per cent of the excess carbon dioxide we release into the atmosphere. This carbon dioxide combines with water to form carbonic acid, making the marine environment more acidic. So far, the ocean is about 30 per cent more acidic than it was before human carbon dioxide emissions accelerated.

The consequences for atolls

Will atolls cease to exist as a result of climate change? The answer is that few scenarios show complete destruction.

Currently, observations across dozens of Pacific atolls experiencing measurable sea-level rise show some islands gaining land, some losing land, and some staying the same size (although sometimes changing in shape).

The reason is straightforward: coastlines are dynamic. Atolls have never stayed the same. Single storms and tsunamis have, at times, substantially altered them. In 1972 a cyclone roared across Tuvalu, leaving behind a new wall made from coral rubble which was larger in area than some smaller nearby islands.

Human action changes the baseline too. Tuvalu’s only international airport was built on wetlands, and the construction compacted the coral rubble beneath. Unsurprisingly, the runway floods.

Not that such situations make for easy living. Geomorphological instability hardly helps people to settle in a place. Furthermore, when sea-level rise is combined with heating and acidifying oceans, ecosystems experience major effects.

Many atolls are separated from the full force of ocean waves and currents by coral reefs. Hard coral skeletons have the same chemical formula as chalk. Chalk dropped in acid dissolves. While, so far, soft corals are performing reasonably well under the impacts of human-caused climate change, increasing ocean acidity does not portend well for hard corals. They are vulnerable to warming seas and other stressors, experiencing a process termed 'coral bleaching'. If an island’s coral reef dies, then the land might not last long in the face of the ocean’s eroding power.

Much is speculation, considering possibilities and pathways without clearly defined outcomes. Consequently, no inevitability exists of atolls vanishing and islanders fleeing. Nor is island life expected to be unproblematic.

The most likely scenario, at least until next century, is major coastline and ecosystem changes. Livelihoods will need to adjust to the transforming environment. Rather than relying on imports, local food will need to adjust to the altered fisheries, weather and soils. However, eating crops grown in brackish water produces adverse health impacts from the salinity.

As encroaching saltwater contaminates the layer of freshwater underneath many atolls, potable water (water that is safe to drink) will be limited. Desalination might be the main option.

If healthy food and water could be secured, then amphibious living might be a prospect. After all, tourist villas in Fiji, Maldives and elsewhere charge hundreds of pounds per night to sleep over the turquoise ocean, listening to waves lapping alongside and gazing down directly to the colourful fish below. If we do it for visitors and cash, will we do it for a people and a country? Both science fiction and design professionals offer further ideas for underwater and floating settlements.

All these approaches keep the atolls habitable and inhabited – with substantive changes to the cultures.

Being ready

These changes are happening now and will continue. While major consequences for atolls might not be felt for decades, the combination leaves a lot of unknowns and uncertainties.

Even if problems do not arise until the latter half of this century, readiness and preparation need to start now. Being ready for huge changes now will help islanders to thrive, avoiding the worst repercussions long into the future.

About the author

Ilan Kelman is a Professor in Disasters and Health at University College London and Professor II at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. His overall research interest is linking disasters and health, including the integration of climate change into disaster research and health research. He wrote the book Disaster by Choice: How our actions turn natural hazards into catastrophes.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.