Hidden in the seemingly mundane bureaucratic letters of the Royal Navy lie some fascinating insights into the role of the British state in providing healthcare and welfare to ill and injured seamen.

As a Caird Research Fellow, I spent months in the Caird Library and Archive examining the 32 volumes of letters concerning the medical administration of the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815).

These volumes contain the correspondence sent from the Board of the Admiralty to the Sick and Hurt Board, which was responsible for medical services in the Navy until 1806. The responses from the Sick and Hurt Board to the Admiralty can also be found here and here.

The letters reveal much about how naval administrators managed occupational health, disability and welfare during the period.

In this article I've attempted to give a picture of how seamen, officers and other naval employees were evaluated as ‘unfit for service’ due to injury, illness or old age: a process known as 'invaliding'.

A second blog, available here, examines what support was available after invaliding.

Content warning: this blog contains content which may cause distress. Some of the historic language expressed is considered offensive, and its presence is not an endorsement of the terms. This language has been retained to reflect the historical context of the times.

What happened to sailors injured at sea?

If a sailor was injured or taken ill in active service, their medical care would be under the direct supervision of the ship surgeon and surgeon’s mates.

The patient would remain on the ‘Sick List’ to recover on ship until they were fit to return to duty. In cases of serious injuries or chronic illnesses, the ship surgeon could give their patients a ‘Sick Ticket’, which referred them to a naval hospital for further treatment.

At hospital, the patient would receive follow-up care from a team of naval physicians and surgeons. If ‘cured’, they would be returned to service where they could resume active duty. In some cases, officers were granted extended medical leave to recover at home rather than in hospital.

From ship to shore: the invaliding survey

If the hospital physicians and surgeons decided that the patient’s condition was unlikely to improve, they would be ‘surveyed’ for invaliding.

A survey would include a medical examination to evaluate whether the patient was likely to benefit from further hospital treatment. Captains or other officers also participated in these surveys to determine whether the patient was capable of their role. This means that invaliding was not decided on medical grounds alone, but also involved a judgement of an individual’s capacity to contribute their labour to the ship.

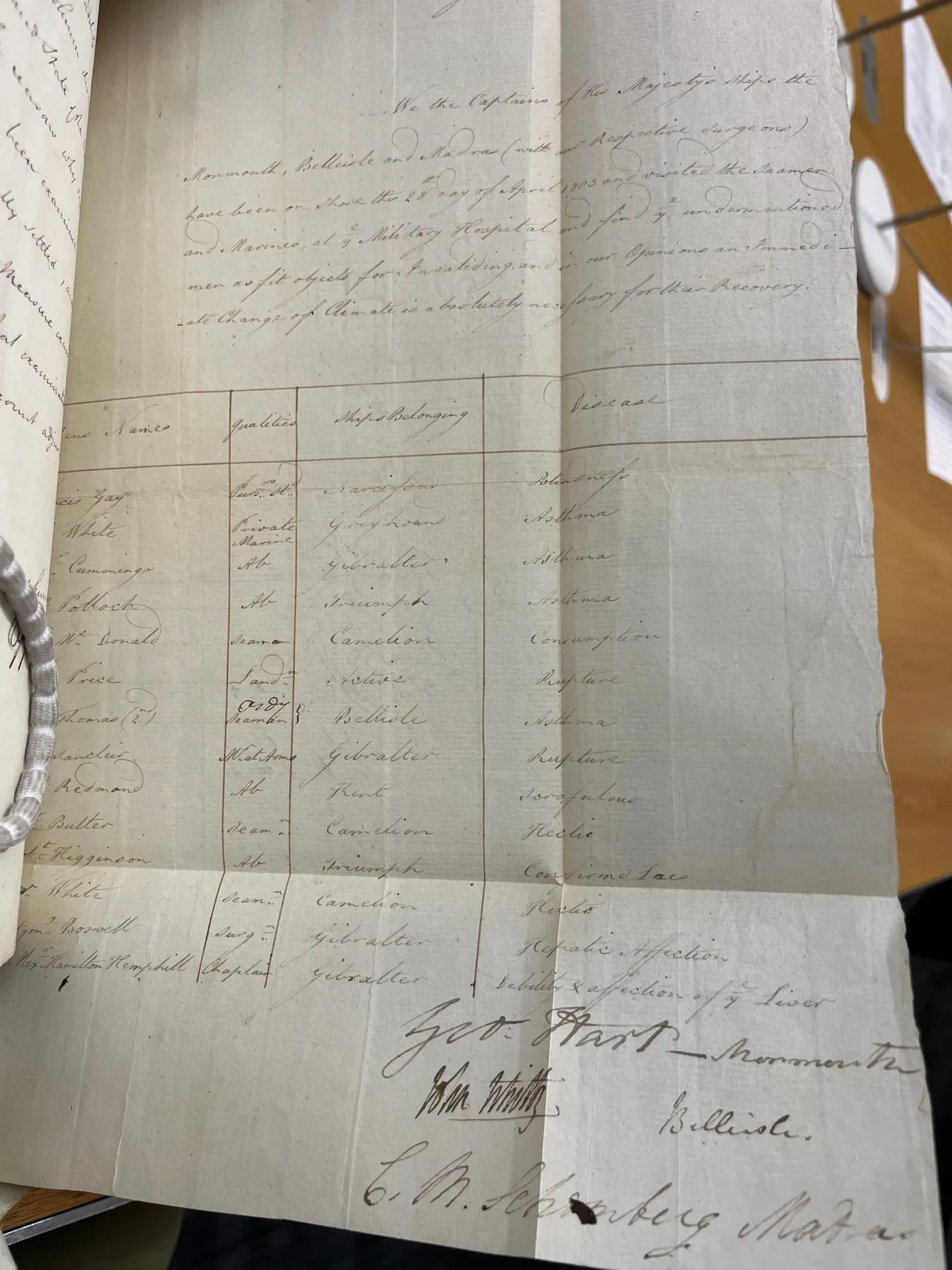

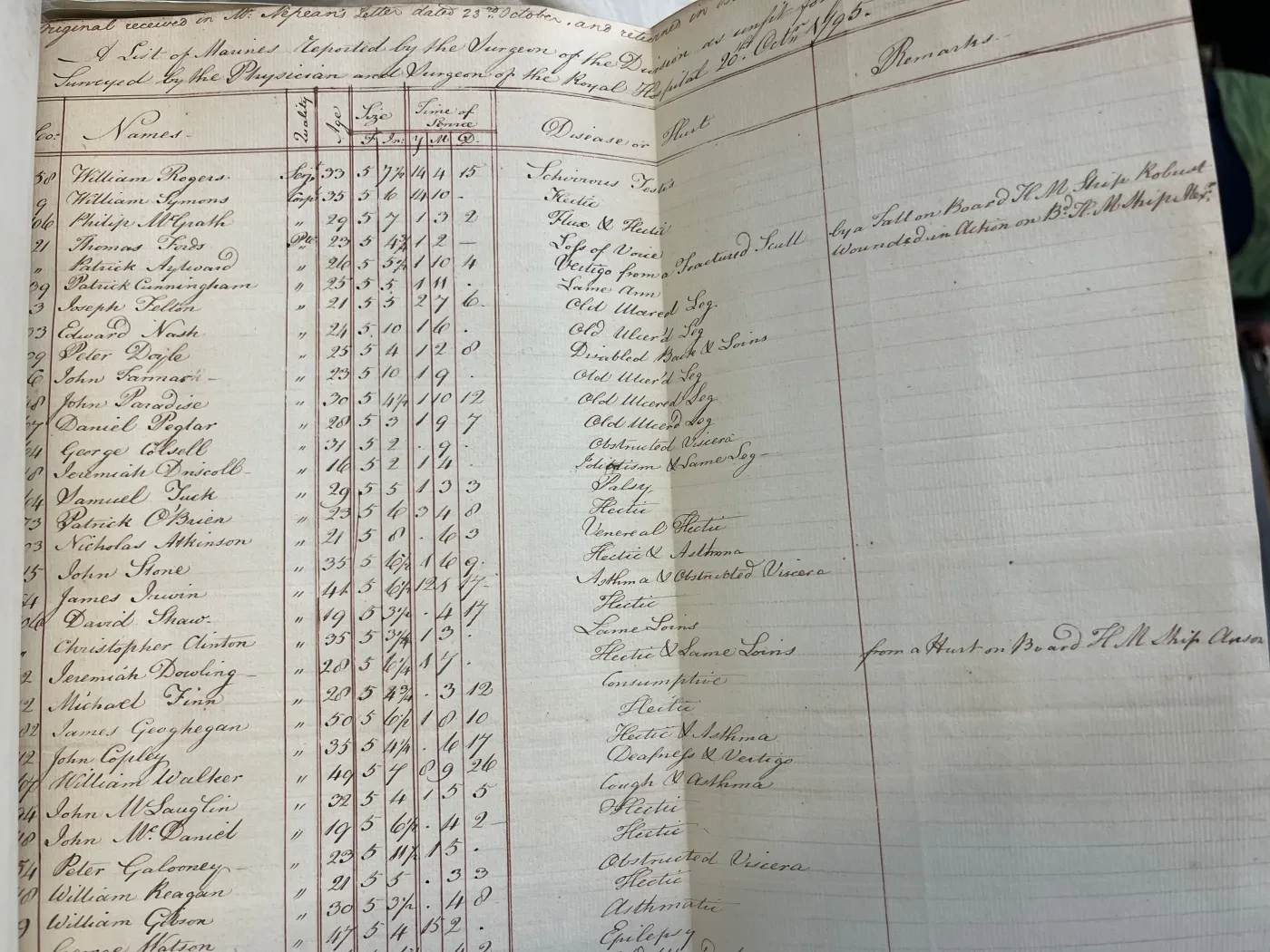

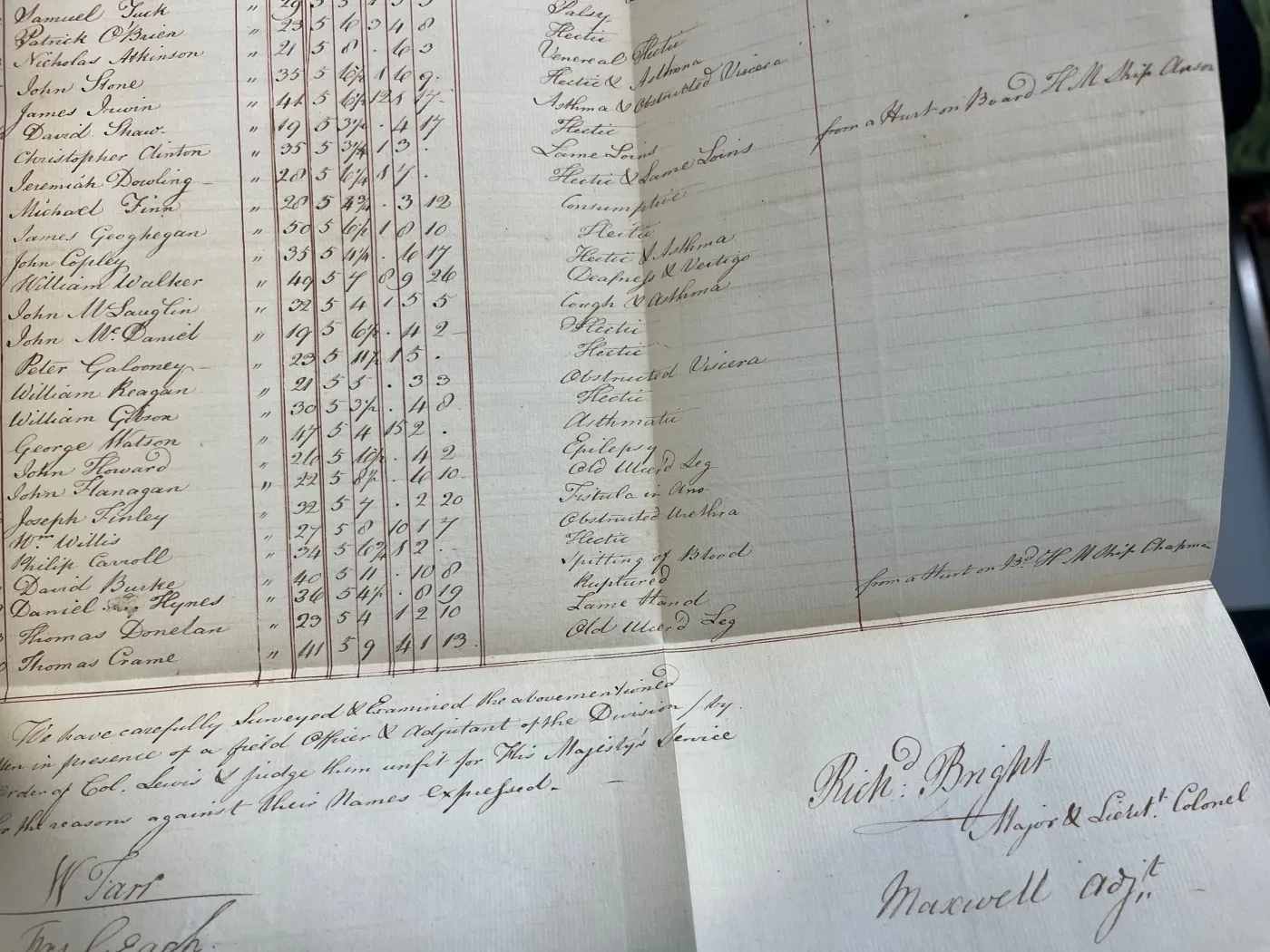

Physicians and surgeons submitted lists of individuals whom they had surveyed and invalided to the Admiralty and Sick and Hurt Board. These lists contain details of each patient: name, rank, age, height, time in service, information on their ‘disease or hurt’, and further remarks.

Inside the archives

Tap the images to explore an example of an invaliding survey carried out at Plymouth Hospital in October 1795.

Inside the archives

Tap the images to explore an example of an invaliding survey carried out at Plymouth Hospital in October 1795.

These invaliding surveys were standardised in June 1801 after a series of complaints were levied against surgeons and physicians at Plymouth Hospital. It was alleged that these medical men had been invaliding seamen by ‘private survey’ – or in other words, without the presence of captains or other naval officers.

To gain greater control over the process, the Admiralty ordered that all surveys in port should occur in naval hospitals rather than on ships or in officers’ private quarters. The participation of non-medical men was also re-affirmed: officers were to be examined by at least one physician, two surgeons, and the hospital governor, while regular seamen were to be examined by three captains and their surgeons (see ADM/E/48 and ADM/F/31).

Invaliding abroad

Invaliding surveys were also conducted on hospital ships as well as on foreign stations. Senior commanders like Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson regularly sent in the results of the surveys conducted in their fleets.

Michael Dillon, a seaman of the Centurion, provides an example of a seaman who was invalided while serving abroad.

Dillon was receiving treatment for a fever and liver complaint in the Bombay General Hospital in India when he 'received a blow on his head from an insane Person'. The surgeon of Bombay General Hospital 'recommended him as a fit object for Charity' since the blow 'has disabled him from serving again in His Majesty’s Service'. The surgeon explained the case in a letter to the Board of the Admiralty, which was then forwarded along with Dillon’s invaliding certificate to the Sick and Hurt Board (ADM/E/48, January 1802).

The invaliding process was normally initiated by surgeons and physicians, but men could also request assessment for themselves. Sometimes the wives, family members or commanding officers of naval workers applied to the Admiralty or Sick and Hurt Board on their behalf.

Attitudes to disability

The relationship between invaliding and disability was complex. Disability was a fluid construct and its impact depended as much on the individual’s rank on ship and their ability to work as it did a medical condition or impairment. What could be 'disabling' to a seaman may not be for an officer.

For example, while the loss of an arm did not prevent Admiral Nelson from continuing in the service, such an injury would have been entirely disabling for a seaman or sailmaker whose manual labour and craft required the use of both arms.

Previous capacity to work with a disability or chronic condition was also a consideration. Lieutenant George Lusk, who suffered from epileptic fits and 'an alienation of the mind', was not considered appropriate for invaliding by the physician of Plymouth because 'he laboured under the disease even when a Midshipman'. Since he had already proven he could work with such a condition, he was not invalided (ADM/E/49, July 1803).

Being invalided from service did not mean that you were unable to work at all. Some men were invalided from sea service to work in the dockyards, while officers made requests to transfer to shore duties. The cook’s position on the ship was also famously given to those who were no longer able to sustain manual labour.

In a very rare case, invaliding came with a promotion.

In December 1796, William Pike, a former carpenter’s mate of the Malabar, was invalided by survey at Deal Hospital as ‘unfit for Sea Duty’. Lieutenant Lewis Cole, the Governor of Deal Hospital, wrote to the Admiralty to requested that Pike be promoted for ‘he is well qualified to act under me as Midshipman or Master at Arms' for Deal Hospital. This was agreed by the Sick and Hurt Board (ADM/E/45, December 1796).

In this case, being disabled from one role clearly did not mean that Pike was unable to continue working in the Navy entirely.

Next steps: what did sailor welfare look like?

There were no standardised criteria for invaliding a naval worker. The decision was subjective, based on the cultural norms of the time and the perception of those making these decisions: physicians, surgeons, captains and officers.

Invaliding surveys were crucial in determining whether the patient qualified for support in the Navy’s welfare system. To read more about the next steps for an invalided naval worker, click here.

About the author

Dr Manon C Williams is a historian of maritime health and medicine. Her research focuses on ship surgeons and the medical administration of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Royal Navy. She is currently a Caird Research Fellow at Royal Museums Greenwich, where she is investigating the invaliding process in the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815).

Further reading

- Teresa Michals, Lame Captains and Left-handed Admirals: Amputee officers in Nelson’s navy (University of Virginia Press, 2021).

- Callum Easton, ‘The Greenwich pensioners and Britain’s naval workforce, 1764–1869’, International Journal of Maritime History 37, No. 4 (2025): 1–24.

- Martin Wilcox, ‘The “Poor Decayed Seamen” of Greenwich Hospital, 1705–1763’, International Journal of Maritime History 25, No. 1 (2013): 65–90.

Join museum experts online for a voyage across the world’s oceans, and explore the legacies of our seafaring past.