Cliff Benson was lying in bed, listening to the radio and waiting for the shipping forecast when he heard a news report announcing that a ship had run aground off the coast of Wales.

‘The news said that an oil tanker had hit the rocks in Pembrokeshire going into Milford Haven. I just thought, “Oh no, I don't believe this.”’

Benson, then in his early 40s, lived in nearby Fishguard and was a volunteer for the local Dyfed Wildlife Trust. His first thought was for the wildlife.

‘I was young in the 1960s when the Torrey Canyon [oil spill] happened in Mount’s Bay in Cornwall. I remembered what a fiasco that was, and the nightmare pictures of all the oiled birds. And I know all the birds around here: I knew what the potential for disaster was.’

Now in his seventies, Benson is the founder of Sea Trust Wales, a charity based in Pembrokeshire committed to studying and raising awareness of local marine wildlife. His efforts mobilising volunteers to rescue sea birds in the wake of the Sea Empress oil spill changed his life.

Phone calls and the 'phoney war'

The Sea Empress had run aground at 8.07 p.m. on the night of 15 February 1996. The following morning, Benson drove to the cliffs at West Angle Bay to see what was happening.

‘You could see the tanker, you could smell the oil and see people cleaning a bit of oil off the beach – although there hadn't really been a lot spilled at that point.’

The ship was carrying more than 368 million litres (130,000 tonnes) of light crude oil. Tugboats initially managed to refloat the Sea Empress and planned to hold it in place until the cargo could be offloaded onto another vessel.

Benson had been told by the Wildlife Trust that the RSPCA was coordinating the official wildlife response and was given a number to call: ‘This was before mobile phones, so every hour or two I went and poured loads of coins into a phone box,’ he says. ‘I just kept them up to date with what was happening.’

He describes the early stages of the grounding as being like a ‘phoney war’, with people rushing to the scene or offering support but with no real signs of harm on land.

‘I managed to persuade the Youth Hostel Association to let us have the youth hostel at Marloes,’ he recalls. ‘They'd had a load of volunteers painting the place, so not only did we have all the accommodation we could ever need, but we also ended up with white paint all over our clothes. That was quite funny, I guess.’

An experienced wildlife volunteer, he was also making his own preparations in case there was a need to help rescue birds: ‘My partner at the time said, “Look, wine boxes are probably the right size for birds. Let’s go around the supermarkets and get as many as we can.” Then we needed something to line them. Initially I thought nappies, but we soon realised how much that was going to cost. So my partner suggested going to the local newspaper and getting the end rolls from their newsprint, because that was designed to accept oil and print and things. We could line the boxes with that.

‘We had a trailer and an old Ford Escort estate, so we were ready. But we weren’t ready…’

Nightmare on Pendine Sands

Severe weather and strong currents meant that the initial plan to hold the Sea Empress in place and offload oil failed. Tugs lost control and the ship repeatedly ran aground, eventually spilling almost 204 million litres (72,000 tonnes) of light crude oil and 1.05 million litres (370 tonnes) of heavy fuel oil into the sea.

Benson remembers receiving a call from the Wildlife Trust area director. ‘He said, “Cliff, can you get to Pendine? From what I hear, there's a bit of a nightmare going on there.”’ Pendine Sands is a stretch of beach 7 miles (11 km) long in Carmarthen Bay, just down the coast from Milford Haven.

‘We jumped in the car and drove to Pendine, and I don’t ever want to see anything like that again. There was just tonnes and tonnes of oil in the water slopping about, with hundreds and hundreds of scoter sea ducks. They overwinter in Carmarthen Bay, and so the oil had come from the tanker and had surrounded them with the tide. And they were just absolutely overcome with it. It was horrible.’

People did what they could to respond, but the damage had already been done.

‘There’s a pub just where you go on to the beach,’ Benson says, ‘and there was a vet there overwhelmed by people bringing in birds: people in ordinary clothes, getting oil all over themselves.’

That day remains Benson's worst memory from the disaster. A government report on the impact of the spill published in 1998 stated that ‘3,500 scoters are known to have died, but peak numbers during the following winter were well below normal and 10,000 fewer than the peak in 1995/96.’

What to do if you find a bird covered in oil

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) advises to contact HM Coastguard if you come across an oiled bird on the coast, or the Environment Agency if the bird is found inland. They also recommend calling the RSPCA if the bird is found alive.

‘Oil is particularly toxic to a bird if ingested, which easily happens when they try to preen off the oil,’ the RSPB says. ‘Please do not attempt to clean birds yourself, it requires specialist equipment and expertise.’

Bird cleaning and patrols

In the days following the spill in mid-February until the beginning of April, Benson organised a team of volunteers who patrolled the coastline looking for oiled birds. These would be recovered, taken to cleaning centres and then monitored for several weeks while they regained their natural waterproofing. Benson estimates that at one point there were between 50 and 60 volunteers working with him, just one part of a huge operational response.

‘It was plastered over the TV what was happening; all over Europe and whatever. There were people who desperately wanted to help, and they'd be sent to us – I guess because we had the accommodation,’ he says. ‘Students, old people, French, German, people from all over.’

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster the RSPCA set up an emergency cleaning centre in Steynton close to Milford Haven. Benson admits that there were tensions between the volunteers and the organisations tasked with managing the official response.

‘They asked us if we could send people – because there was quite a lot of us by then – to help them clean the birds,’ Benson says. ‘And, basically, they had four sinks and not enough water. The water pressure was so slow, and it was taking something like 30 minutes to clean each bird.’

‘I’d met a good guy, a local RSPB inspector, when I went in there. And I said, “How's it going?” And he said, “Come look at this.” When we went round the back of the place there were just skips full of dead birds.’

The report into the environmental impact of Sea Empress concluded that, ‘Given the enormity of the task, the collection of birds, first aid and transportation generally worked well.’ It acknowledged that the number of birds at the cleaning centre in Steynton exceeded capacity and said that there were challenges involved in training and managing some volunteers. It recommended that the RSPCA establish ‘strong links’ with regional groups, given that ‘in any oil spill that affects birds, numerous small local organisations and wildlife hospitals will play a vital supporting role’.

Despite Benson's frustrations, there were other moments where working with the authorities brought results. He recalls that during a patrol at Martin’s Haven on the peninsula, he noticed a group of farmers who had come and begun hosing down the rocks, sending oil back into the sea rather than collecting it.

‘I said to this guy, “What are you doing?” He replied, “Well, we’ve just been told that’s what we do.” Then I saw a guy come down in a suit, and I thought, “Right…” I said, “Excuse me, who are you?”

‘He said, “Oh, I’m from Texaco. I’ve just come to see what’s happening and what we can do.” So, I explained and he just said, “Right, you lot stop. We’ll get people here to do this properly.” We then went and had a cup of tea and a chat, and he asked what they could do to help. Which is fair play; it was their oil.

‘They ended up giving us a load of protective clothing and masks and wellies and all that stuff. So that did help, because until that point we were going around the second-hand shops asking for any clothing we could get – we were just getting filthy all the time. So instead of being in second-hand clothes, we suddenly had these proper coveralls and gloves and everything else. So that was something.’

Learning from the past

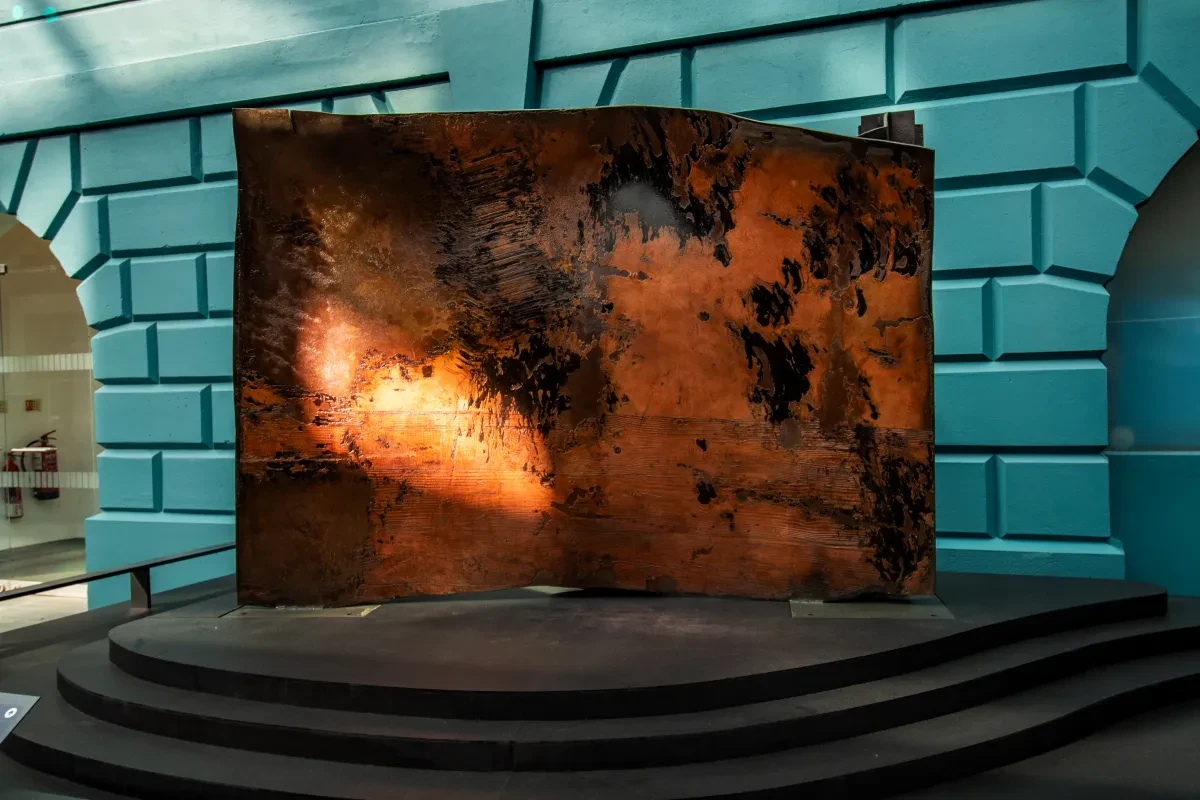

Thirty years on from the Sea Empress oil spill, a section of hull from the ship is on display at the National Maritime Museum – a symbol of the impact that maritime industry can have on the environment. Explore the legacy of Sea Empress, and meet the people working to prevent disaster at sea today.

Find all the stories in this series

‘If the spill had happened a month later, it would have been untold tragedy’

The Sea Empress environmental impact report concluded that, ‘in several cases the environmental impact was not as severe as many people had initially feared,’ thanks in part to the time of year the accident occurred, as well as the type of oil spilled and the patterns of winds and tides which carried much of the oil away from sensitive parts of the Pembrokeshire coast.

Benson agrees that the time of year was a major factor in the outcome.

‘Skomer Island was a real worry for us. Luckily there was a gang of old wardens that went over onto Skomer and cleaned up The Wick, which is a major seabird colony,’ he says. ‘The amazing thing was, it being February, all the puffins, razor bills, guillemots and the thousands of birds that usually breed there – not to mention something like a third of a million Manx shearwaters – hadn’t arrived yet. If the spill had happened just a month later, it would have been untold tragedy.’

Some of the birds that Benson brought in for cleaning were ringed before release in order to track their progress: ‘Some of them actually turned up three, four, five years later, which proved it had been worth it – at least for some of them – to be cleaned and rescued.’

Looking back now, he says the experience with Sea Empress ‘sowed the seed’ that later grew into Sea Trust Wales, the marine conservation charity he founded in the early 2000s.

‘We needed to put some local capability and knowledge together,’ he says. ‘It occurred to me that if people come here and learn [from Sea Empress] but then go away, that knowledge goes with them. That’s why we’re here now.’

More than a year after the Sea Empress oil spill, for instance, Bensons notes he began to spot dozens of porpoises from Strumble Head near where he lived. He speculated that they had moved further round the coast to avoid the effects of the oil but knew that without community engagement there would be no way of monitoring the creatures in the long term.

‘Cetaceans’ – whales, dolphins and porpoises – ‘are at the top of the food chain,’ he explains. ‘If they’re doing OK it’s like a litmus test: you can tell how good or bad the situation is over time. We needed to get a group of people together to start learning.’

Sea Trust Wales today

Now the charity runs education programmes and carries out regular marine surveys from its ‘Ocean Lab’ headquarters in Fishguard Bay. It also tries to work with the local fishing and maritime industries to protect the marine environment.

‘We have a project called Recycle Môr. Môr is the Welsh word for sea. Fishing gear over the years has just been thrown over the side when it’s finished with, where it traps fish and birds or slowly breaks down into microplastics.’

Sea Trust Wales arranged for recycling bins to be put in the main fishing ports around Pembrokeshire to collect end-of-life equipment. The fishermen responded. Now the challenge is to work with government to increase the recycling capacity.

‘We’re collecting it quicker than they can take it,’ Benson says. ‘It’s high-quality stuff and expensive to produce. If you recycle it, it should become part of a circular economy.’

For Cliff Benson, projects such as these are the real legacy of Sea Empress.

‘Looking back, I was all hyped up with it, and what did we do? We saved a few birds at the end of the day,’ he says. Looking around the headquarters of Sea Trust Wales, he adds, ‘This is what we’ve done.’

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.