An emergency at sea is different to an incident on land.

The size of the vessels, number of passengers or hazards of the cargoes, not to mention the frequently wild and inaccessible locations, all pose unique challenges when ships run into difficulty.

But there is another, perhaps less obvious, difference when it comes to maritime emergencies.

‘Say there’s a major accident which requires a motorway to be closed. The police will close the road, the fire service will come to rescue people, ambulances will take them away for treatment and so on,’ says Stephan Hennig, the Secretary of State’s Representative for Maritime Salvage and Intervention (more on that job title later).

‘At no point in that scenario would any of the authorities say to the car drivers, “Right, start cleaning this up.” And that is the key difference: the distribution of responsibilities,’ Hennig says. ‘Because at sea that is precisely what commercial entities are duty-bound to do under international and national regulation.’

Maritime ‘salvage’ – the recovery of a damaged, stricken or wrecked vessel and its contents – is a commercial operation carried out by specialised, experienced and well-equipped teams. ‘No country can have the amount of assets to be everywhere and do everything,’ Hennig explains. ‘The duty on the authorities is to ensure that those commercial parties discharge their duties in the appropriate manner.’

That’s where the Secretary of State’s Representative for Maritime Salvage and Intervention, or ‘SOSREP’ for short, comes in. The role was created following an investigation into the Sea Empress disaster of February 1996, in which more than 204 million litres (72,000 tonnes) of oil spilled into the sea close to the port of Milford Haven in Wales.

‘The role was created in 1999,’ Hennig says. ‘It gives the state an instrument to make decisions during maritime emergencies that either threaten safety or have the potential to cause significant pollution.’

As a single individual tasked with coordinating the salvage response, Hennig is uniquely placed to explain what happens during an incident in UK waters.

‘You will always be thankful, in that one moment when something goes wrong, that you’ve prepared for it’

What kind of incidents do you respond to?

I’m probably involved in between 40 and 70 incidents per year.

The UK is a maritime nation with a phenomenal amount of traffic in our territorial waters, not least in the Dover Strait and the English Channel – one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. Just like cars on the road, vessels can encounter engine and mechanical problems. It’s just that problems can be a lot more complex on 300- or 400-metre-long vessels, which consequently means they usually take a lot longer to fix.

The idea of the SOSREP system is about early notification. It doesn’t have to be a grounding or collision, which is almost starting at the back end, where you need to respond to something that’s already gone wrong. My deputy or I may be notified if, for example, repairs are taking too long for comfort, or the issue occurs close to the shore. There’s obviously a difference if a vessel loses engine power five miles from the shore versus 50 miles out to sea.

The degree of urgency may be different, but what applies in all cases is that we need the ship owners – and, if required, insurers or salvors – to take the correct steps to prevent that breakdown from carrying over into something more significant that might endanger the ship’s crew, other vessels or the environment. The role is as much preventative as it is reactive.

How are you informed of an incident?

Well, sadly everyone in the industry – certainly in the salvage industry – has my number! But ordinarily the notification process goes from the ship – what we would call the casualty – to the Coastguard. The Coastguard gathers information and determines whether they need to notify other on-call duty officers in the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, who then make further assessments. They determine whether they need to call the SOSREP or not.

That’s the ordinary chain of notification, but sometimes it works the opposite way round, where either a salvor or a marine insurer calls me directly about a problem with one of their vessels that nobody else in the chain knows about. It becomes a bit messy then, because you need to say, ‘OK, well, first of all you need to tell the Coastguard and we need to close that information loop.’ There’s no point stepping in at the top of the chain if the bottom doesn't know that there’s something going on.

It’s not a planned system, but in a way it’s a system of redundancy: nothing really should fall through the cracks. I always say to say to colleagues, both in industry and in government, ‘I’d rather know than not know’, because if I know I can decide whether I need to do something about it.

If a situation is serious enough, the National Contingency Plan describes how you may assemble a ‘Salvage Control Unit’. What is that?

The Salvage Control Unit typically involves representatives from all the stakeholders in the incident, usually a single representative, because the smaller your cell the quicker you can make decisions. It’s very much an operational cell, involving only the individuals that have a direct involvement in the salvage response.

I will have the final say on what happens operationally, even though the suggestions for how the problem should be resolved rest with the commercial parties. They will explain what they’re planning to do, and that then either gets approval from me or, with help from technical advisors and specialists, we have a discussion. But it’s a comparatively small group of individuals affecting the outcome of the incident. Of course we work with the other stakeholders who, quite rightly, have a vested interest in the incident and its consequences, but not in that Salvage Control Unit, because that is very much focused on the technicalities of solving the problem.

Who is typically involved?

On the water, responsibility for the ship sits with the ship owners and managers, insurers and commercial salvors. When something goes wrong it is still a commercial issue – albeit the significance might be such that the state might have to become involved.

On the government side, it depends. The Maritime and Coastguard Agency is my employer, but in an incident I have an individual function that essentially is detached from all of government.

I have a duty to inform all the relevant government departments, both the Maritime and Coastguard Agency and the Department for Transport, of what's happening. When it comes to potential impacts on the shore, we also have local authorities, environmental regulators or protection bodies that all have an interest.

And is this in an actual room? Do you all meet up?

Well, we can’t pick our locations! In the past we’ve used everything from village halls and hotel meeting rooms to Coastguard centres and port offices.

COVID certainly taught us you can do quite a lot of things remotely. Nothing replaces being in the same room with people, but in the interests of time you can have calls to work out if the incident is manageable remotely or whether we need to deploy closer to the scene. It all depends on the severity of the initiating incident and the proximity to shore.

On the first day of national lockdown in March 2020, for example, we had a ship grounding off the west coast of Scotland. Our entire response system that we would normally activate was not on the cards; we couldn’t take the risk with a global health pandemic.

So, we had to make do: salvors could go because they could form their own bubble, and pollution responders too, if required – but those were the only parties deployed to the grounding. That incident lasted 42 days, and it was only on the last day when we brought the ship into dry dock [watch the timelapse below] that I drove there to see the ship arrive safely. We conducted all meetings via good old-fashioned telephone conference call.

How much contact do you have with the ship and the crew?

Communication between the ship and the shore is usually via VHF [very high frequency] radio, and that’s through the Coastguard operation centres. But where a vessel needs outside assistance, be that a towage company or a salvor, then there might be a salvage master or a salvage crew placed on board the ship, and we then have direct communication with them.

What drives your decision-making in an emergency?

Obviously our first concern is for the ship’s crew. Then we look at whether the incident has the potential to affect the safety of other seafarers or anyone on land. Then there is the environmental impact and the protection of property.

For any incident, however, whether it’s a notification with a watching brief or a full-blown response, my consideration is always: ‘What’s the worst-case scenario? What’s the absolute worst thing that could happen as a consequence of this, and how can we prevent it from happening?’

Why worst-case rather than best-case scenario?

This is something we’re very bad as humans at accepting. Following an accident or an incident, there may be one outcome where we tidy it all up, but with anything in between there are only variants of bad. In a way there are no good elements because the accident has already happened.

I think the case study for that would be the MSC Napoli in January 2007. During the response operation the decision was made to deliberately beach the ship. The considerations were: do we run the risk of this vessel breaking apart at sea in one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, with thousands of tonnes of fuel oil, over 2,000 containers and two bits of ship endangering large tracts of the environment and the safety of other shipping? Or: do we run this thing up on the shore in a place where we can essentially have an element of control? There are consequences whichever way you look at it, and they’re all bad.

Documentary on the salvage of MSC Napoli, ©PKFV

Communicating that is obviously quite important so that people don’t get the wrong impression. To run a ship up a beach deliberately, that’s a hard call for anyone to make – master, salvor, authorities, ship owner – but you would make it in the interest of avoiding something worse.

How did the role of SOSREP come about?

In the aftermath of the Sea Empress grounding and the subsequent environmental pollution, there was a demand for a public inquiry. That inquiry was led by a former High Court judge, Lord Donaldson of Lymington, and one of the key recommendations was the creation of this role. He even gave us the abbreviation ‘SOSREP’ – he must have recognised that it takes a very long time to say the full title!

The Marine Accident Investigation Branch had identified that in the immediate aftermath of the initial grounding there was a lack of coordination between the various authorities. The incident occurred in port-controlled waters, so there was an element that said that the Port Authority had an obligation to coordinate the response. But, obviously, in an incident of such significance, local administration and central government also became involved. There was a lack of delineation over who should do what, and that probably caused delays in decision-making.

That was Lord Donaldson’s takeaway: if we could streamline the coordination and give decision-making power to a single individual empowered to act and make decisions, we could prevent that kind of issue happening again.

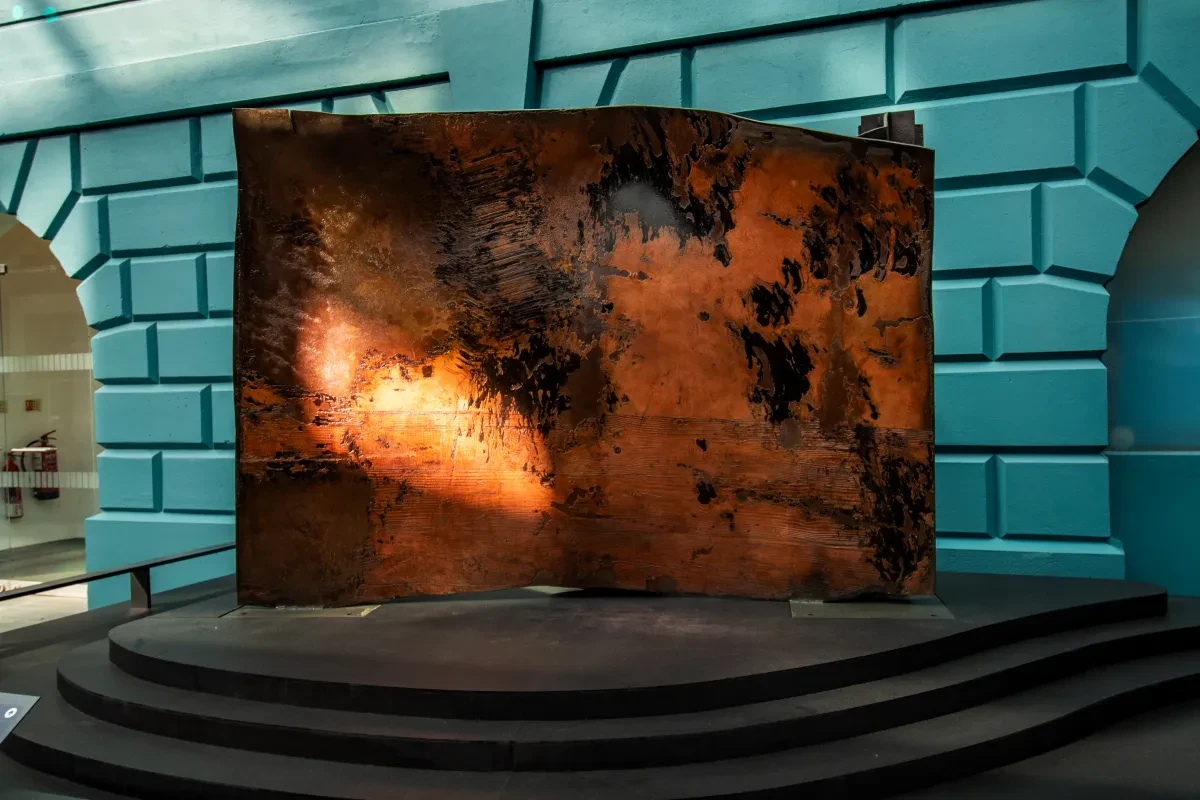

Learning from the past

Thirty years on from the Sea Empress oil spill, a section of hull from the ship is on display at the National Maritime Museum – a symbol of the impact that maritime industry can have on the environment. Explore the legacy of Sea Empress, and meet the people working to prevent disaster at sea today.

Find all the stories in this series

What’s the legacy of the Sea Empress today?

Certainly in salvage and in the marine insurance sector, both the Sea Empress and the Torrey Canyon spill of 1967 are still important case studies. There is an acute awareness of those pivotal incidents that have effected change, and a recognition that the Sea Empress review directly led to the creation of the role I’m in today.

News report on the Torrey Canyon disaster (courtesy of British Pathé, ID 2023.39)

How has the role changed since it was established?

The core responsibilities don’t change. They’re well enshrined and well practised, and people in the maritime sector understand how it works in terms of responsibility and who can make decisions.

But nothing ever stands still. When the first SOSREP was involved in the grounding of the MSC Napoli, at the time that was one of the largest container ships in the world with 2,400 TEU [Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit, a general unit of cargo capacity]. Here we are, barely 20 years later, dealing with ships with 24,000 TEU – that’s a significant challenge in terms of the technical response required.

How does the UK compare to other countries in how it handles emergencies?

Cooperation is really good, certainly with all the administrations that we share boundaries with. We all have different ways of working, but if we’re talking about the way that the SOSREP system operates, it’s unique. There is not really any other administration that delegates decisions to single individuals acting on behalf of administrations.

There’s recognition in the maritime sector, particularly among insurers and salvors, of our system, because you can streamline so much. But it obviously puts a lot of pressure on the person in the role to act as a sort of buffer between all the different stakeholders.

How do you respond to the pressure that comes with the role?

When you have an emergency and you need quick decisions, you can only make decisions based on the facts you have at that moment of time in the interest of preventing this bad scenario from going too catastrophically badly. And somebody’s got to make the decision.

Control, I think, is that illusion. We’re in control of very little. If you repeat the mantra, ‘I can only control things up to a point.’ The elements, sea, weather – I have no control over that. We can only work with what we’re given. And once you appreciate that and you work in this field for long enough… I’m not saying it’s easy at any given moment, but it becomes easier when you realise what your limitations are, and that all the parties – whether in industry or in government – are working towards the same outcome. We may have different ways of getting there, but from the outset we’re committed to preventing this from going terribly wrong, so let’s pull together and resolve this together.

Are you always on call?

My deputy and I share on-call duty. However, legally, the role is set up for a single decision maker in maritime emergencies, so when my deputy is on call and something is so urgent that it might require government intervention through this role, she’ll have to defer to me – unless I’m out of the country.

Is that hard to handle?

I mean, I’ve worked in maritime incident response for 20 years now, initially in a Coastguard Operations Centre and then as a duty officer for the last 13 years. So, I know what the gig is. When the phone rings and it's so urgent that you think, ‘Right, I better pack now’, that’s already well-rehearsed and the family tolerate it.

What incidents stand out for you?

There was a car carrier in the approaches to Southampton that had gone on its side and took three weeks to remove. For a ship that had been lying at an angle of about 50 degrees, that [salvage operation] was quite an achievement, with no significant pollution in the ensuing salvage.

Marine Accident Investigation Branch report into the grounding of the Hoegh Osaka

In 2016 we had a semi-submersible drill rig that was being towed for recycling in Malta. As it was being towed around the Outer Hebrides, the tug lost the tow during a storm. The drill rig sat on the beach for two and a half weeks until salvors managed to refloat it. In all, it took three months to resolve.

Most recently I was involved in the 2025 collision off the Humber between a container vessel and a tanker [the Solong and the Stena Immaculate]. They’re all kind of big events and in the public eye, but at the end of the day you know what the problem is, you do your best together with all the parties to bring it to a resolution as quickly as possible.

What do you do when you’re not responding to emergencies?

We run exercises and scenarios with ship owners, insurers and salvors and other organisations. We attend professional development events, and we share knowledge. In this line of work everybody seems to know everybody, which is phenomenal for an industry that is truly global. You will come across the same people, sometimes working for different organisations as the years go, and it’s valuable to have that continued experience.

That’s dropping off, however, and it’s a concern both in industry and administration. Where previously you would have had people working in the same industry for 30 or 40 years, you just don’t have that anymore, which means you no longer have that accumulated corporate knowledge.

That’s a challenge for everybody: there’s a generational gap, and maritime has always been a little ‘out of sight’. It’s only in the public eye when something goes wrong.

Do you find it odd that a lot of that work rarely sees the light of day?

When you’re working on the first stages of an incident, you do a lot of work in preparation for the worst case. And a lot of work that you do – thankfully! – never comes to anything. Now, that could be quite depressing if you think you’ve done all that work and nothing comes of it, but in fact it’s great: you will always be thankful, in that one moment when something goes wrong, that you've prepared for it.

Did you always want to work in maritime?

I’m from northern central Germany and had no connection to the sea until I moved to the Shetland Islands 25 years ago, when I still thought I was going to be a teacher.

As part of my university degree there was a teaching assistantship. After I sat an interview, the exchange body decided where they were going to place me. And there was this little box insert in an atlas – nowhere near to where it really is! – and I thought, ‘Oh, islands, that sounds interesting.’

Eventually I realised that teaching was maybe not what I wanted to do, so I started in the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Lerwick. I worked as a watch officer for seven years. It was shift service: you worked two days and two nights and then had three-and-a-half days off. And it was search and rescue coordination, but also putting out maritime safety information to mariners and to people on the coast.

After being in the operations room, I became a counter pollution and salvage officer based in Aberdeen, working with stakeholders around Scotland and Northern Ireland, but also doing emergency response. That’s where I met my predecessor, who I worked with for five or six years before he retired. He asked me one evening, in terrible Scottish west coast weather during a ship grounding, whether I could imagine being his deputy. Obviously, I still had to go through the proper recruitment, but eventually I became the deputy SOSREP. Then my predecessor retired and I was asked to fill the role temporarily until we could recruit, and now here we are.

None of this was planned, which for that part of my life I quite like! In emergency response, you need to be quite structured in how you respond to problems. I’m quite happy to have this element of my life be more meandering.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.

Main image: Car carrier Hoegh Osaka stranded on Bramble Bank (Photo © James West via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Feature image: The Lysblink Seaways aground off Kilchoan in February 2015 (courtesy of Stephan Hennig)