Around two-thirds of the world’s ocean is considered international waters. This area lies beyond the authority of any single country.

The high seas, however, are not lawless. Seafarers, ships, companies and nations are all subject to international law.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is one of the most important international treaties governing what happens in and on the ocean. Sometimes called the 'constitution for the ocean', UNCLOS was agreed in 1982 and entered into force in 1994.

UNCLOS declares that that ‘the high seas are open to all States’, granting countries rights such as the freedom to navigate, fish and conduct scientific research. The convention also asserts that all nations ‘have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment’.

While the convention is meant to ensure global responsibility for the ocean, there is a potential problem: if the ocean is for ‘everyone’, is it anyone’s priority to care for it?

One potential answer to that challenge is the United Nations High Seas Treaty – officially known as the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction.

It’s a long title, but it represents a potentially groundbreaking update to international law.

How did we reach this point, and how might the way the maritime world is governed help safeguard the future of the ocean? Learn more with the National Maritime Museum.

What are the High Seas?

The seas and oceans are considered to be a ‘global commons’, which means that they are free for all.

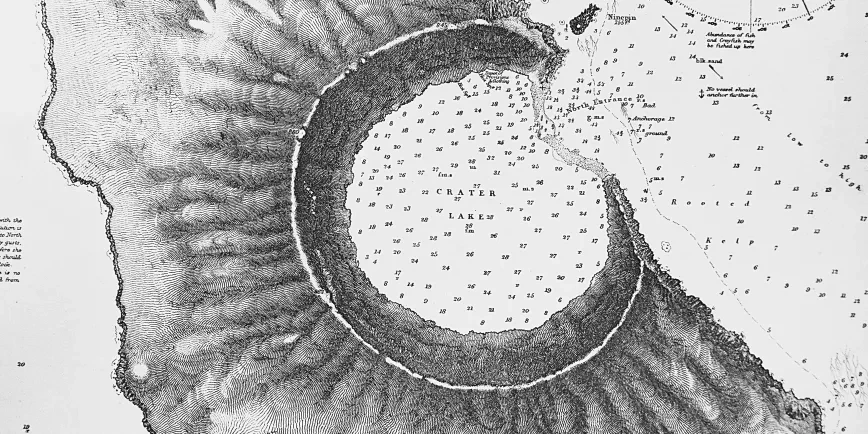

But there are differences in how various ocean areas are governed. UNCLOS created a system of maritime zones:

- Territorial Sea (up to 12 nautical miles): This area is under full control of the coastal state, similar to land territory. Foreign vessels have the right to navigate through it – a right known as 'innocent passage'.

- Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (up to 200 nautical miles): The coastal state has exclusive rights over all natural resources, both living and non-living, in this area. The country also has responsibility for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, managing resources such as fish stocks and preventing over-exploitation.

- Continental Shelf: the coastal state has the right to exploit the natural resources of the seabed and its subsoil in this area. This right may extend beyond the 200-mile boundary, depending on the geography of the area.

- High Seas (beyond 200 nautical miles): This area is beyond any national jurisdiction.

The Convention on the Law of the Sea recognises that the area of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction is the ‘common heritage of mankind’, and that ‘No State shall claim or exercise sovereignty or sovereign rights over any part of the Area or its resources’.

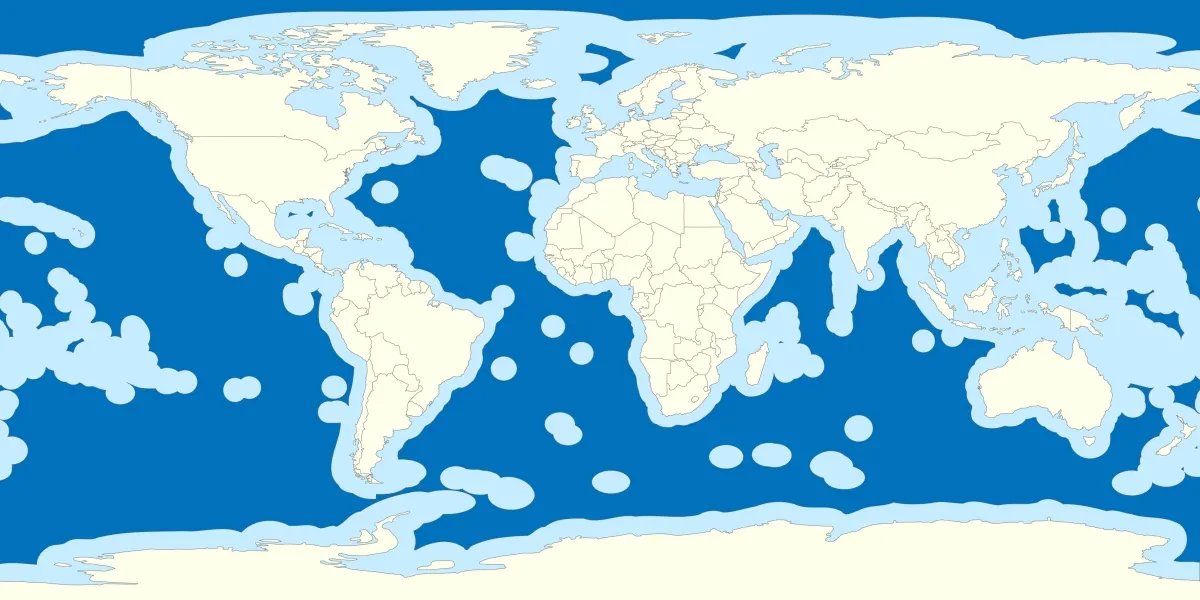

A map of the world showing Exclusive Economic Zones. The areas in dark blue are the high seas.

Map by B1mbo, CC BY-SA 3.0 CL, via Wikimedia Commons

What does maritime law have to do with ocean conservation?

Maritime law is a complex system of laws, conventions and regulations that govern activities on the seas and oceans.

It covers a huge range of issues, from navigation, shipping, seafarer welfare and piracy to fishing, pollution, oil and gas drilling, deep sea mining and marine conservation.

Treaties like UNCLOS can therefore can play a vital role in ocean protection and health of our planet. Countries need to work together to combat climate change and manage human activities in and on the sea.

However, while UNCLOS compels nations to work together to protect the marine environment, it does not set out detailed instructions for how to do it.

Negotiations to change this have been ongoing for more than 20 years. The result is the so-called UN High Seas Treaty, an agreement reached in March 2023 and set to enter into force in 2026.

'From oil to tin, diamonds to gravel, metals to fish, the resources of the sea are enormous. The reality of their exploitation grows day by day as technology opens new ways to tap those resources.'

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – a historical perspective

What is the UN High Seas Treaty?

The official name is the ‘Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction’. It is commonly referred to as either the UN High Seas Treaty or the BBNJ (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction) Agreement.

The treaty creates specific laws and processes designed to expand UNCLOS's broad commitment to ocean protection.

For instance, it establishes a framework for creating marine protected areas (MPAs) in areas beyond national jurisdiction. These are designed to ‘protect, preserve, restore and maintain biodiversity and ecosystems’. This framework could be key to protecting 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030, one of the key targets of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

'MPAs are among the most powerful tools that we have to protect critical habitats, species, and ecosystems. They have the potential to mitigate and even reverse the negative impacts of various threats. Scientists have found them to be valuable tools for safeguarding biodiversity, protecting top predators, and maintaining ecosystem balance.'

The treaty also requires countries to conduct Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) on planned marine activities, such as deep-sea mining, before they are authorised. This is designed to lead to better understanding of human impacts on the ocean and challenge actions ‘that may cause substantial pollution of or significant and harmful changes to the marine environment’.

Also covered are the fair access to and use of marine genetic resources – genetic material derived from plants, animals, or microbes – and access to marine technology.

‘Covering more than two-thirds of the ocean, the Agreement sets binding rules to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity, share benefits more fairly, create protected areas, and advance science and capacity building. As we confront the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution, this Agreement is a lifeline for the ocean and humanity.'

António Guterres, United Nations Secretary-General, September 2025

When does the High Seas Treaty come into force?

The final text for the treaty was agreed in March 2023 and adopted in June later that year. However, to become law, it needed to be ratified by at least 60 countries.

That milestone was reached on 19 September 2025, which means the treaty will come into force on 17 January 2026.

The UK was one of the first countries to sign the agreement in 2023, but has not currently ratified the treaty. A Bill is currently going through Parliament that, once passed, will allow the UK to ratify the treaty.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.

Main image: Seascape by John Everett (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Bequeathed by the artist 1949)